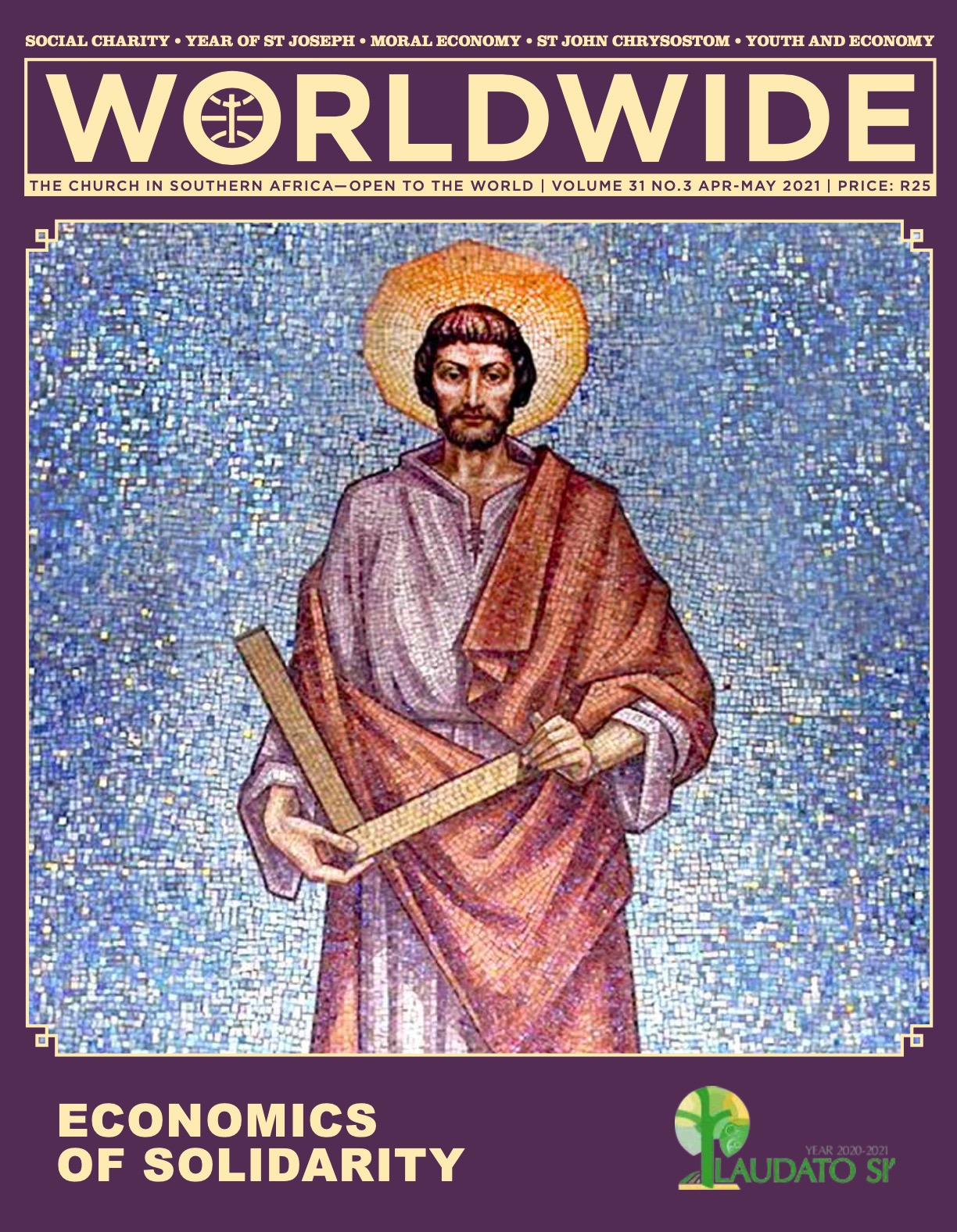

St Joseph and The Dignity of Human Work

We are celebrating the Year of St Joseph. He is, for us Christians, an example of honesty and fidelity, a model of the father figure in the family. He is the humble and firm man who sustained the Holy Family through very difficult situations. This mosaic, portraying him as a carpenter, reminds us of the dignity of human labour. Through work, we become collaborators in the building of society, contributing to it with our various talents. Job creation and sharing of opportunities need to become part and parcel of a new economics of solidarity. Social charity, sustainability and respect for the environment will be integral elements of that model that aims at respecting the dignity of every person.

SPECIAL REPORT • ECONOMICS IN AFRICA

with an understanding of how to conduct high-quality analysis of applied labour economics.

Cape Town University, South Africa. Photo: UN-WIDER-Flickr

New Paths for African Economic Development

BY BARTIMAEUS MATHEBULA | PRETORIA

AFTER 25 years of continuous vigorous economic growth and poverty reduction in Africa, COVID-19 has put these on temporary halt, according to the 2020 report by the African Centre for Economic Transformation (ACET). The economic impact of the disease has been quite devastating, even if the virus was slow to arrive on the continent’s shores. However, if the situation is seen also as a challenge, Africa may have an opportunity to improve her governance and attractiveness for investment and to support her community-based initiatives operating in the informal sector.

At the beginning of the decade, Africa’s expected Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was 3.9 %, according to the African Development Bank (2020), but Covid 19 and the lockdown resulted in a contraction of its GDP of 3.4%, in 2020. Nevertheless, the United Nations (UN 2021) estimates an economic growth for Africa also of 3.4% this current year. Looking at particular situations, in South Africa, for example, there were 1.7 million less jobs in the third quarter of last year compared to when the pandemia struck, according to 2021 State of the Nation Address (SONA 2021). The strict lockdown led to an estimated contraction of the economy of 7.7% for 2020 and an employment rate of 32.5% at the end of the year (Eyewitness News 2021). However, the prediction for 2021 is of a South African economic bounce-back of 3.3% (UN 2021).

Most of the African governments responded quickly to the Covid-19 emergency and citizens respected orders of staying at home. The official measures were structured around a three-stage approach: saving lives through health and epidemiological efforts; preserving livelihoods through social and economic support for families and the private sector; and protecting the future by investing in structural policies that will help ensure job creation and economic growth.

Ghana, for example, committed $100 million to support preparedness and response, and another $166 million to support selected industries, while the South African Reserve Bank reduced interest rates and announced measures to ease liquidity conditions. The African Development Bank also floated $3 billion as a “Fight COVID-19” social bond (ACET 2020).

Aloysius Uche Ordu, editor of Brookings Africa Growth Initiative, assessed the situation with the following words: “The global economy halted and Africa’s growing, largely informal, service-based economy was forcibly shut down to pre-empt the disease’s spread. Until that point, the region was experiencing unprecedented growth — though, that growth was, disappointingly, largely jobless and not necessarily in the most productive sectors.” (Ordu 2021).

Acha Leke, senior partner and chairman of the African region from McKinsey & Company, also comments: “As the world begins to emerge from the economic crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic, the big question in Africa — beyond how do we protect the health of average citizens — in 2021 is how and when Africa will begin its exit from the first economic recession in a quarter of a century.” (Leke 2021).

“African governments have already spent 1–7% of their GDP on domestic stimulus packages. However, the funds made available among African nations for response and recovery are less than one percent if compared to the amount deployed among the world’s richest nations.” (UN Economic Commission for Africa 2020).

Covid 19 and economic conditions

No doubt, COVID-19 has been a pro-found crisis, but this can also be seen by governments as an opportunity to make meaningful policy changes that will not only help in the short term, but also strengthen the long-term recovery efforts. Emergency situations are often occasions for lasting reforms. A crisis can be the moment to build trust in government institutions and between government leaders, citizens, and stakeholders, to seize the chance of taking difficult policy decisions. It often exposes which policies, programmes and institutions are not working and enables successful short-term policy measures to turn into medium to long-term reforms by creating new incentives for individual stakeholders. In the case of COVID-19, it can serve as a reminder of the need to build economic resilience for a better capacity and preparedness to deal with economic shocks in the future (Amoako 2020).

It is therefore important to consider the context in which Africa will find herself in the coming years so as to see what kind of reforms may be prioritised. Two lines of action might help, if done simultaneously, namely an improvement in the conditions and trust for investments in the states and support of community-based and grass root initiatives.

The Institute for Security Studies (ISS) published a report entitled, Why Africa’s development models must change: understanding five dynamic trends (Scheye & Pelser 2020). It analyses five dynamics that will greatly influence the future conditions in which the continent may find herself in the near future. These dynamics can be seen, not necessarily as obstacles, but also as challenges for new patterns of growth in Africa.

The authors of the study recognise that most of the prior development models presupposed that economic growth in the continent would have derived from the movement of people and capital from low-productivity agriculture into higher-productivity industrial manufacturing and services. This has not occurred in Africa as foreseen.

The reality has been quite different. In fact, a rapid urbanization has brought into the cities a paramount increase in the informal sector of the economy, rather than higher industrial productivity or job creation.

Informality does not necessarily imply poverty always, but it generally means tax evasion. However, businesses can start informally and move into the formal sector should the conditions become favourable to them.

So far, the formal sector has not been the engine of economic growth in the continent. On the contrary, in sub-Saharan Africa, informality absorbs up to 89.2% of the total employment, and for the youth the figure rises to 94.9%. In Africa as a whole, it accounts for 50–80% of the GDP, 60–80% of the overall employment and 90% of the new jobs. In 2018, 92.4% of economic units were informal in the continent (ACET 2020).

Informal economy, even though generating jobs of low productivity and high insecurity, has been growing more rapidly in most African countries than large-scale modern manufacturing. We can ask ourselves what are the reasons for the informal sector to prevail despite efforts made in the expansion of the formal economy. In South Africa, for example, in the last quarter of last year, the employment in the formal sector increased by 1.8%, whereas the informal employment was up by 2.6% (Bhengu 2021).

The authors of the ISS report (Scheye & Pelser 2020) analyse five factors that could give an explanation of the growth of the informal sector and they may give us a hint for the necessary developmental models that will fit into the concrete reality of the continent. These factors are as follows: climate change, urbanization, infrastructure, pandemics and lawlessness. They will likely condition the overall development that African countries can expect in the years to come.

Five dynamic trends

Climate change is disturbing the rainfall variability in the continent and particularly, it will become more acute in countries near the equatorial region. Furthermore, as 95% of all sub-Saharan crop production is dependent on rain, African agriculture will be subsequently distressed by climate change. As a consequence, prizes of food and water will likely increase, and food security might be threatened. Women may suffer the most, as many of them are rural farmers. Rain variability and its effects will fuel a rise in migration, estimated at 85 million people or 4% of the population of the continent in the coming years (Scheye & Pelser2020). Another consequence of climate change has been the rapid increase of the phenomenon of the grabbing of resources, mainly water and land. Firms and investors, mostly non-Africans, are purchasing or leasing big portions of fertile or humid land on African soil, originally destined for food production, making them produce crops for agro-fuels or renewable energies. However, these investments in land and water have hardly brought any benefits to the local population, in terms of job creation or social advantages, but only more food insecurity and migration.

The impact of climate change calls for an urgent commitment to the environment, education towards recycling and the better use of natural resources, drastically reducing down the emissions of CO2 to the atmosphere.

Urbanization is the second factor considered in the ISS report. It is occurring in Africa at the fastest rate in the world with a current figure of informal housing of 62–75% of the total habitation and a prospect of an increase in urban land by 600% by 2030. The cost of living in African cities, particularly housing and food, is 55% and 35%, respectively, more expensive than in comparable developing countries, and the cost of labour is high as well. As a result, African urban firms employ 20% fewer workers than elsewhere. This continuous urban expansion, in a setup of poor infrastructures and services, results in low productivity rates, increases inequalities and creates largely jobless economic progress.

There are also challenges posed with the growth of many African cities, as Bello-Schunemann et al. puts it: “Uncontrolled, rapid urbanisation in the context of pervasive poverty, inequality, large youthful populations and lack of economic opportunities does not bode well for the future sustainability of Africa’s towns and cities. Unplanned, overcrowded urban settlements populated with marginalised youth can be hotbeds for violence, particularly in lower-income informal areas.” (Scheye & Pelser 2020).

Urbanization becomes a challenge. Governments might need to invest in rural areas and create opportunities in middle size cities, avoiding an overwhelming population influx into African capitals.

Infrastructure is the third factor that the ISS report takes into consideration. The continent’s services of power, water, transport and communications are twice as expensive as elsewhere. For instance, the average cost of electricity to manufacturing enterprises in Africa is close to $0.20 per KWH, around four times higher than industrial rates elsewhere in the world. Mobile and internet telephone charges in Africa are about four times higher than those in South Asia and international call prices are more than twice as high. Infrastructure needs an annual amount of investment of $130–170 billion, while the current spending is $75 billion (Scheye & Pelser 2020).

The announcement of Cyril Ramaphosa, President of South Africa, of a programme of investment in infrastructures, such as water, transport and telecommunications valued at R340 billion and an increase of energy generating capacity of 11 800 MW, seem promising moves in the right direction (SONA 2021). Africa has a tremendous potential for renewal energies, and it needs to tap into it in order to become self-sufficient, creating a more competitive environment that attracts new investors.

Epidemics and pandemics such as COVID 19 and others will likely become frequent. Their devastating effects on health and economics calls for investing in health facilities so as to meet shortages in medical staff and equipment. The poor and vulnerable are the most exposed to diseases and the ravages of health hazards.

Lastly, lawlessness combines crime and violence with a common public perception of a relative absence of the rule of law. It includes criminal behaviours, ranging from everyday common crimes to organised crime. It also refers to non- criminal behaviours, such as non-payment of taxes or lack of compliance with business regulations. In recent times, it looks like lawlessness has been normalized, looking at the rising crime rates, unshackled corruption and many citizens refusing paying for public services or taxes. Moreover, the continent is unable to tackle the scourge of organized crime because embedded state officials are the most prominent and virulent type of organised criminal entrepreneurs.

The fight against corruption must continue being a priority so as to be able to use public resources for the service of the people, averting tax loopholes too. However, assisting the informal economy is not incompatible with the fight against corruption, especially if some actors of that sector start contributing to public finances, thus entering into the formal sector of the economy.

According to the ISS report, given this context, despite the necessary efforts to combat corruption, calls for the creation and development of a ‘strong central state’, coupled with the need ‘to fix the state,’ are not only idealistic, but deeply misguided. It is the very structure and behaviour of past and existing state officials and the institutions they control that has profoundly contributed to the current condition of lawlessness. Moreover, a lawless environment is also a precipitating cause of violent extremism (Scheye & Pelser 2020).

Rays of hope

Under these circumstances, two parallel lines of action could be considered. Firstly, in a situation in which states seem to fail or not to perform as expected, hope often comes from the grassroots of society. The resilience of the local neighbourhood and the outcome of the communities become inestimable resources to rely upon. They respond to many challenges and show capacity to face a variety of obstacles. They need to be enhanced and their resources to be tapped and locally managed accordingly. The state could play an important role supporting financially small and medium-scale initiatives (SMIs) that emerge in the neighbourhoods. Politics and development policies must also give a preferential attention to the informal sector.

Secondly, after the immediate COVID-19 crisis abates and the necessary economic and social adjustments are made, African economies will hopefully move as quickly as possible to regain lost GDP, jobs, revenues, investments, and productivity, helping to ensure Africa’s growth and transformation. the challenge will be to convert the encouraging prospective macro-economic figures into real integral development for the people within a more just, equitable and fair society. An economy of solidarity also fits well in the traditional values of the African society.

As seen above, the pandemic can become a catalyser of necessary and neglected actions before COVID, now more critical than ever, so as to recapture gains lost during the crisis — and to accelerate economic transformation afterwards.

| Dates To Remember |

|

April 1 – Holy Thursday; 2 – Good Friday; World Autism Awareness Day; 3 – Holy Saturday/Easter Vigil; 4 – Easter Sunday; International Day for Mine Awareness and Assistance in Mine Action; 6 – International Day of Sport for Development and Peace; 7 – International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda; World Health Day; 11 – Divine Mercy Sunday; 21 – World Creativity and Innovation Day; 22 – International Mother Earth Day; 25 – World Malaria Day; 28 – World Day for Safety and Health at Work; 30 – Our Lady, Mother of Africa May 1 – St Joseph the worker; Workers Day; 3 – World Press Freedom Day; 8 – Remembrance and Reconciliation for the Victims of the Second World War; 15 – International Day of Families; 16 – Ascension of the Lord; World Communications Day; 20 – World Bee Day; 22 – International Day for Biological Diversity; 23 – Pentecost Sunday; 24 – Closure of Special Laudato Si’ Anniversary Year; 29 – International Day of UN Peacekeepers; 30 – World No-Tobacco Day |