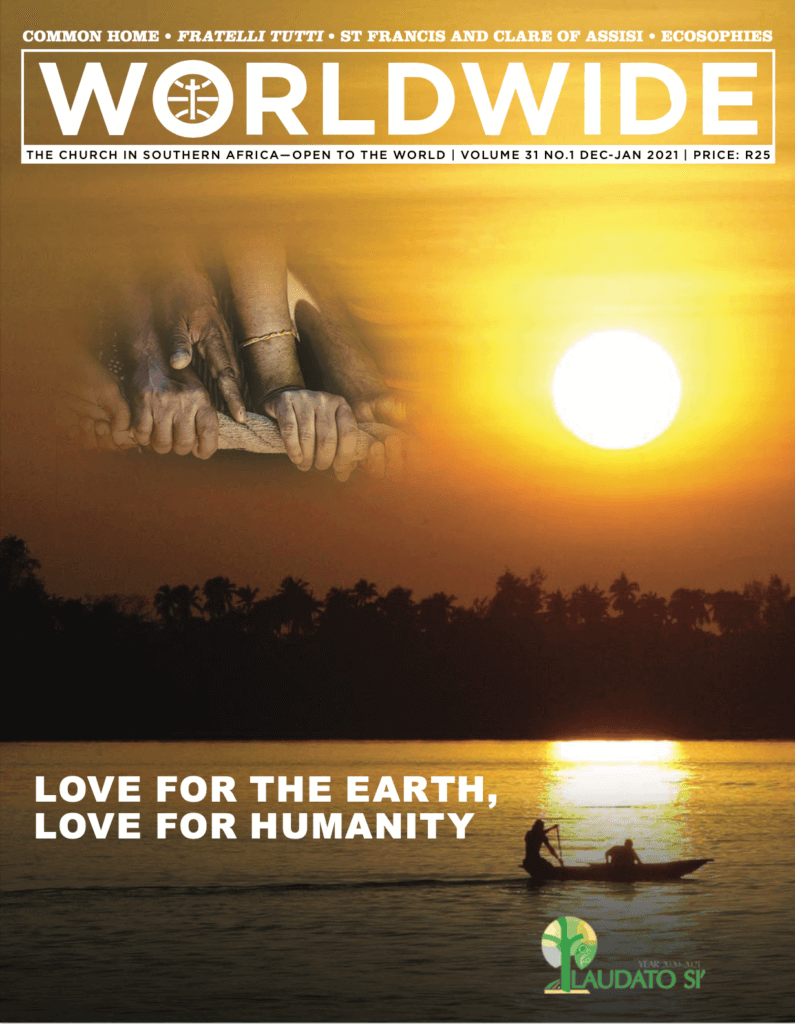

Love for The Earth,

Love for Humanity

The bright light of the rising sun represents the luminosity, the beauty inherent in each human being and our capacity to transform evil into good and to establish authentic human relationships. The closeness of the celebration of Christmas envisions the coming of the Light and Peace for the world, the One that fulfils the greatest aspirations of any person and leads us all to God.

We’ve Got to Start Thinking Beyond

Our Own Lifespans

If We’re Going to

Avoid Extinction

WHEN YOU place bacteria in a test tube with food, their population grows exponentially until, eventually, they run out of resources and kill themselves off. The comparison with humanity’s predicament on the climate crisis has looked glaringly obvious even a couple of decades ago; but we have not really strayed since from the inevitable path to extinction. The Corona Pandemic, the biggest global crisis for decades that we are living through, should be the shock we need to change course — yet it already seems unlikely that much will change. It’s easy enough to throw around the old adage ‘never waste a good crisis’ — but when it comes to existential questions about the future of humanity, it has proved fairly useless.

Corona virus or not, we remain locked into a treadmill that measures progress by growing GDP rather than by wellbeing and environmental sustainability. This is an economic paradigm that has served most of us — particularly the most affluent — pretty well for decades, though the richer we’ve got, the more the benefits have tailed off. There have been a number of studies showing that, beyond a certain point, more wealth does not necessarily equal more happiness — true at a societal level as well as an individual one.

There is a lot that could account for this flatlining. It was once assumed that increased productivity, driven by technological progress, would result in us having more leisure time: see John Maynard Keynes’s prediction in the 1930s that we’d be working just 15 hours a week by now. Instead, luxury beat leisure and an explosion in consumerism has driven us towards ever more consumption. The ‘happiness’ economist, Richard Layard has also pointed towards “disorders of development” such as obesity and tech addiction (although often in a wealthy society, obesity is associated with poverty).

The costs of this consumption have increased. Much of it is subsidised by labour exploitation, both at home and abroad. Then there is the small issue of catastrophic climate change, as we race towards tipping points beyond which global heating becomes self-reinforcing and harder to halt without unprecedented levels of coordinated international action.

The idea of moving towards a ‘zero growth’ economic model starts to look increasingly unattainable. Nevertheless, if we want to preserve the planet and achieve a better work-life balance we would have to sacrifice gains in material living standards. If we could protect the least affluent from any negative impacts — which would require more redistribution — why not?

The big problem is, of course, no one knows how to get there. We can’t afford to waste this opportunity to rethink economic recovery over broader measures of wellbeing, even as the government has prioritised pubs over schools in relaxing the lockdown.

Our political and economic systems are utterly indisposed to the radical shifts we need to promote wellbeing over wealth and protect the planet. Short-termism is everywhere, from politicians who face elections every few years to company directors who must account for quarterly results. On the right, there are powerful vested interests who want to maintain business as usual — who go quiet in the wake of a crisis (just look at Davos agendas in recent years), but who do all in their power to obstruct change. The left often makes peace with continuous growth, despite its costs, because a rising tide makes redistribution easier. It is crazy to think that a shock to GDP caused by a financial crisis or a pandemic could be used as a bridge to a different world because the brunt of the pain is always, always borne by the least affluent and the young.

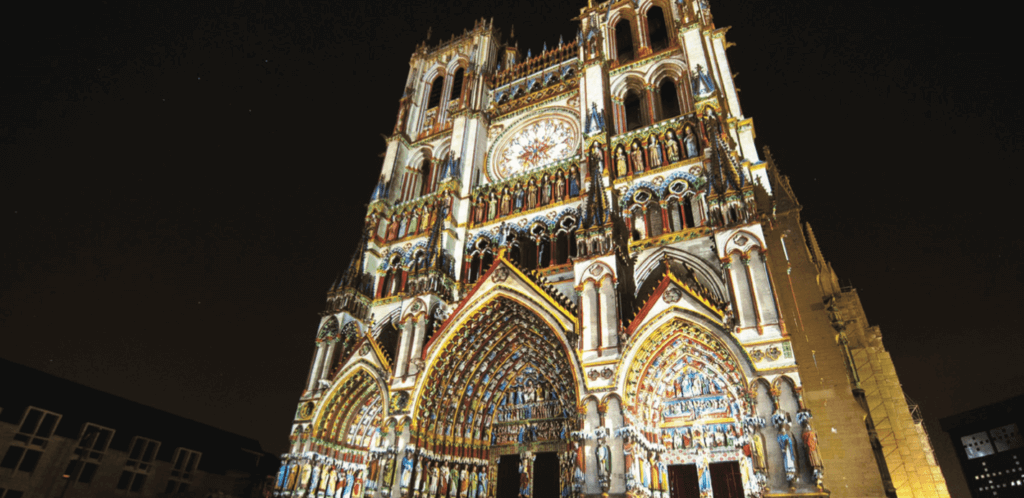

So, we need to think far more about the mechanisms and institutions that could get us on to a different path. The Long Time Project is exploring how humans could shift their time horizons so, simply put, we feel more emotionally connected to our future descendants. It points to the fact that we tend to view our future selves, let alone future generations, as strangers. We need to rewire the way we think about the future, and our own ageing and deaths; art and culture can play an important role in it. We could learn from those times in history when humans have proved their ability to think beyond their own lifespan: ‘cathedral thinking’ is based on those architects who planned spectacular buildings that would never be finished in their own lifetimes.

It’s no exaggeration to say that, unless we find a way to think differently about consumption, wellbeing and sustainability, we will be responsible for our own extinction. It should be clear by now that crises such as extreme weather, pandemics, financial crises are never going to be the wake-up call that forces us to confront our own fragility. A good crisis inevitably goes to waste, and it is lazy and irresponsible

to think otherwise.

{Sonia Sodha, www.theguardian.com}

Could the Pandemic Create a Less Exclusive Economy?

THE COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the global crises that were already there, the recognition of a dysfunctional economy and the driving force behind highly unequal societies—which favour new paths, fears and hopes, but the future remains unknown.