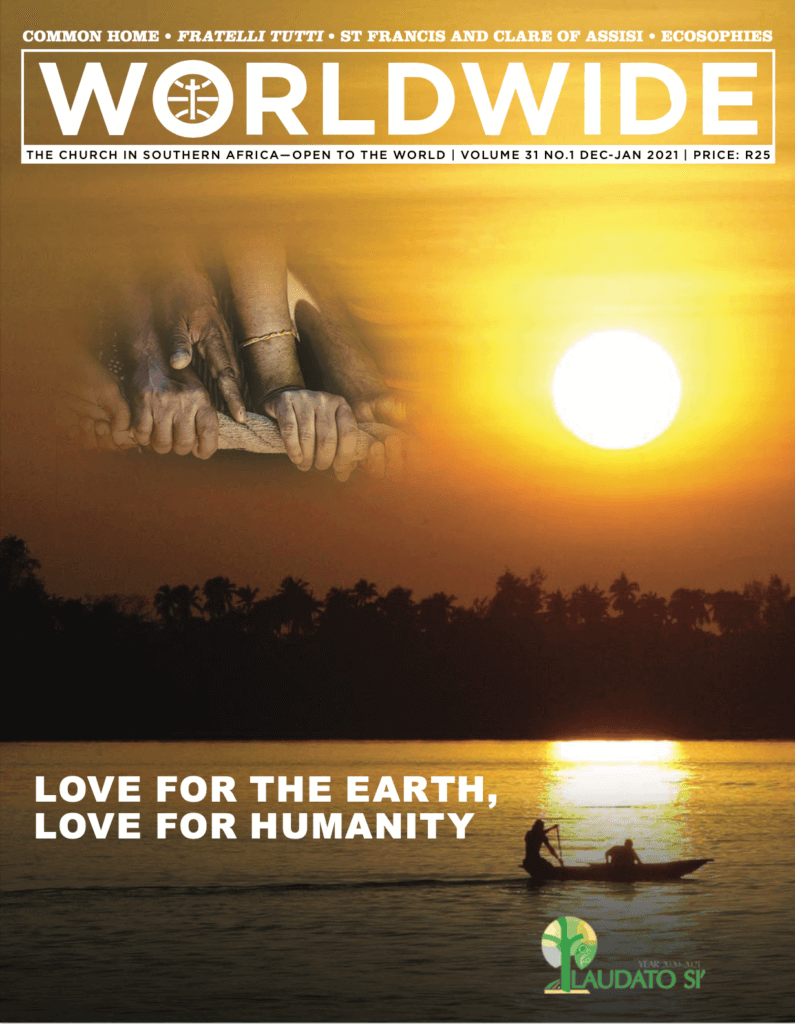

Love for The Earth,

Love for Humanity

The bright light of the rising sun represents the luminosity, the beauty inherent in each human being and our capacity to transform evil into good and to establish authentic human relationships. The closeness of the celebration of Christmas envisions the coming of the Light and Peace for the world, the One that fulfils the greatest aspirations of any person and leads us all to God.

POVERTY, JUSTICE, ECOLOGY, THEOLOGY:

A FRUITFUL DIALOGUE

There are those who wonder why religions have taken an interest in the ecological question in recent years and, above all, what they can contribute to a seemingly technical debate. In the case of the Catholic Church, the answer is simple: her interest lies on the close connection between environmental degradation and vulnerability of the most disadvantaged or fragile: the poor, children, the sick, the elderly, women, indigenous peoples and racial minorities

BY JAIME TATAY NIETO SJ | PROFESSOR OF ECOLOGY, ETHICS AND SOCIAL DOCTRINE OF THE CHURCH AT THE PONTIFICAL UNIVERSITY OF COMILLAS, MADRID

WITH THE passage of time, other reasons and motives have been added to this initial interest in the ecological question, such as the importance of thinking about future generations or the value of creation itself, as a gift from God and a place of encounter with Him. However, there is no doubt that the social question was the gateway to the ecological question for Catholics. There is a phrase in Pope Francis’ encyclical (2015), Laudato Si (LS), that explains it clearly and directly: “Many of the poor live in areas particularly affected by phenomena related to warming, and their means of subsistence are largely dependent on natural reserves and ecosystemic services such as agriculture, fishing and forestry. They have no other financial activities or resources which can enable them to adapt to climate change or to face natural disasters, and their access to social services and protection is very limited. For example, changes in climate, to which animals and plants cannot adapt, lead them to migrate;

this in turn affects the livelihood of the poor, who are then forced to leave their homes, with great uncertainty for their future and that of their families” (LS 25).

Indigenous populations and poor farmers in developing countries are the most exposed to the impact of environmental degradation, although they are not the only ones. The evidence accumulated over the last few decades shows that certain groups in all countries — rich and poor, South and North — suffer disproportionately from the impacts of biodiversity loss, natural resource depletion, pollution, scarcity of water and its poor quality, rising sea levels, deforestation, overfishing, extreme weather events or uncontrolled mining. All these groups have been given special attention by the so-called environmental justice movement. They have incorporated into their analysis, the findings of ecological economics, feminist thinking, environmental ethics and racial and post-colonial studies. We will refer to them below in order to establish a dialogue and thus being able to perceive more clearly the similarities and differences between environmental justice and the Catholic thought on ecology. There are new practical initiatives that have been launched in various Christian communities trying to offer a response to the threefold challenge of our time: to build a world in which social peace, economic justice and environmental sustainability reign.

ECOLOGICAL SENTINELS AND SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION

In the opinion of the French thinker Éloi Laurent (Laurent & Prochet 2015), there are certain groups of people who are privileged witnesses when it comes to seeing and understanding what is happening to our planet. They not only see, hear and analyse, but also smell, touch and feel in their own bodies the effects of deforestation, disappearance of fauna, pollution, erosion, drought or migration. They know well that ecological and human degradation go hand in hand. In the contemporary environmental debate, a number of expressions have become popular that come from environmental activism and the experience of the ecological sentinels: climate justice, food sovereignty, bio-piracy, land grabbing, ecological debt, environmental racism or environmentalism of the poor are some of the best known.

For Joan Martínez-Alier (2005), an economist at the University of Barcelona, Spain, as well as for Laurent, these recent expressions, often used by political ecology and ecological economics, have been developed and deepened by the thoughtful reflection of academics, but it is the experience, denunciation and creativity of indigenous peoples and marginalised groups that have generated them. In this sense, the much quoted 1855 letter from Chief Seattle of the Suwamish tribe to President Jefferson of the United States can be considered one of the first testimonies of socio-environmental activism available to us. One of its most significant paragraphs is worth reproducing: “The earth does not belong to man; it is man who belongs to the earth. All things are related like the blood that unites us all. There is a union in everything. What happens to the earth will fall on the children of the earth. Man did not weave the fabric of life; he is merely one of its threads. Whatever he does to the fabric, he will do it to himself”.

Seen from the Christian tradition, the denunciation of Chief Seattle of the Suwamish tribe and of the ‘sentinels’ referred to by the scholars, resonates in some way with the biblical tradition, and especially with the prophets as seers, men and women capable of anticipating the future and warning of the risks to which present decisions lead. The prophetic dimension of the Christian faith can be perceived in the words of Pope Francis himself when he affirmed, in a phrase often quoted, that “today we cannot fail to recognize that a true ecological approach always becomes a social approach, which must integrate questions of justice into discussions about the environment, in order to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” (LS 49). With the passing of time, the intuitions and denunciations of the first ecological sentinels have expanded to include new and unsuspected aspects. An example of this expansion was the experience that led to the coining in the 1980s of a new term to denounce environmental racism.

Laurent calls them ‘ecological sentinels’ because they — poor people, children, women, the elderly, indigenous people — are the ones who experience the impact of environmental

degradation in a more direct or dramatic way

MARGINALIZED MINORITIES AND ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM

For the population as a whole, racial minorities and impoverished social groups have traditionally lived closer to polluted areas or where the quality of public services, air, water and food is poorer. This is a sociological reality about which there is already ample evidence in many parts of the world. As a result, these communities are exposed to a greater number of pollutants or pathogens, or live in areas where the environmental risk of floods, droughts or extreme weather events is greater. In recent years, we have witnessed these differential risks first-hand both in developed countries such as the US and Australia and in developing countries such as Mozambique and the Philippines.

Since these social groups have neither the political influence nor the economic power to move, to lobby their parliaments or to influence national policies, they are often chosen to locate activities or projects of higher environmental risk in their vicinity, whether they are mining, industrial, agricultural or livestock operations.

Benjamin Chavis of the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice (1987) defined environmental racism as “racial discrimination in the deliberate targeting of ethnic and minority communities for exposure to toxic and hazardous waste sites and facilities, along with the systematic exclusion of people of colour from environmental policy making, law enforcement and reparation”. The definition emerges from the concept of environmental justice, understood as “the fair treatment and meaningful participation of all people without regard to race, colour, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies”.

The well-founded criticism of the racism that is latent in many contemporary socio-environmental problems also coincides with the analysis of post-colonial studies, which have highlighted the impact that colonisation has had and continues to have on the way natural resources are extracted, how the wealth they generate is distributed and the environmental impact of their extraction, processing and commercialisation. The Church has echoed this reflection.

A direct reference to it appears in Laudato Si, when it is stated that “there is a true ‘ecological debt’, particularly between the global North and the South, related to commercial imbalances with consequences in the ecological sphere, as well as to the disproportionate use of natural resources historically carried out by some countries” (LS 51). Another veiled reference to this issue appears in the criticism of certain ‘green’ proposals from developed countries: “The imposition of these measures penalizes those countries most in need of development. Thus, a further injustice is perpetrated under the guise of protecting the environment. The poor end up paying the price” (LS 170). As always, the thread is cut by the weakest. Together with the contribution of the environmental justice movement, which has incorporated criticism of racism and the neo-colonial dimension of the dynamics of environmental degradation, feminist thought has also contributed significantly to revealing another of the cultural dynamics that has led us to the current situation.

WOMEN’S VISION AND UNHEALTHY DUALISMS

One of the currents of contemporary thought that has converged in the complex ecological movement is that of feminist thought. A number of women academics—including several theologians—have made significant contributions to this field over the past 50 years. Following the publication of Le féminisme ou la morte (d’Eaubonne, 1974), the first to address the environmental question from a gender perspective, thinkers such as Rosemary R. Ruether, Sally McFague, Vandana Shiva, Ivone Guebara, Anne Primavesi or Yayo Herrero have stated that one of the reasons for the current ecological crisis is cultural: the dualistic approach that has established a set of false dichotomies or oppositions between culture or nature, mind or body, reason or emotion, scientific or traditional knowledge, independence or dependence, man or woman. Along with this split, Marta Pascual and Yayo Herrero point out that “all eco-feminisms share the vision that the subordination of women to men and the exploitation of nature are two sides of the same coin and respond to a common logic: the logic of patriarchal domination and the subordination of life to the priority of obtaining benefits”. Moreover, our (capitalist) culture “has developed all sorts of strategies to subdue both and relegate them to the realm of the invisible. That is why the different eco-feminist currents seek a profound transformation in the ways in which people relate to each other and to nature, removing formulas of oppression, imposition and appropriation, and overcoming anthropocentric and androcentric visions”.

Although Catholic social thought does not share all the approaches of eco-feminism, it is legitimate to say that there are elements of the critique to dualistic thinking and the revaluation of the feminine in our contemporary culture that are being incorporated into the ecclesial reflection and praxis. So much so that, right at the beginning

of his encyclical.

Later, he will make a critical examination of the history of Christianity to recognize that Jesus “was far removed from philosophies which despised the body, matter and the things of the world. Such unhealthy dualisms, nonetheless, left a mark on certain Christian thinkers in the course of history and disfigured the Gospel” (LS 98). Pope Francis recognizes, in a way similar to many contemporary thinkers, that the dualistic thinking has distorted the Christian message. He also turns his attention to the future generations.

Pope Francis affirms that “our common home is also like a sister, with whom we share our life and a beautiful mother who opens her arms to embrace us” (LS 1)

THE DISTANT NEIGHBOUR AND THE FUTURE NEIGHBOUR

The contemporary icon of environmental activism is a Swedish youngster named Greta Thunberg. Although her person raises passions for and against, it is true that she has helped to raise awareness and mobilise a multitude of children, adolescents and young people with regard to ecological problems. Some of the arguments she has articulated in her speeches refer to social injustice and the damage done to other forms of life, but above all to the impact that environmental degradation will have on the future generations she represents. This is an old argument in the field of ethics, already developed by Hans Jonas in his well-known 1979 essay, The imperative of responsibility (the so-called intergenerational responsibility) although it is already present in most religious and philosophical traditions. It is also a type of argumentation that has articulated the environmental discourse of most religious and ecumenical statements, including the Catholic one. Pope Benedict XVI insisted in his encyclical (2009), Caritas in Veritate, that “economic and social costs of using up shared environmental resources are recognized with transparency and fully borne by those who incur them, not by other peoples or future generations” (CV 50).

Pope Francis, years later, will recall these words to link intergenerational responsibility to the social question: “Our inability to think seriously about future generations is linked to our inability to broaden the scope of our present interests and to give consideration to those who remain excluded from development. Let us not only keep the poor of the future in mind, but also today’s poor, whose life on this earth is brief and who cannot keep on waiting” (LS 162). In the case of Christianity, monastic life is particularly enlightening since it is a way of life based on stability. It always seeks a presence, in a territory, that is oriented towards the future, lasting in time — sustainable, we would say, today — to which the innumerable well-preserved natural spaces that we find around religious communities bear witness. Nevertheless, the extension of the temporal radius of moral consideration that the new ecological consciousness proposes, extends not only to the distant neighbour (those of our contemporaries who suffer the injustice of environmental degradation), and the future neighbour (those who will come in the future), but it also points to the rest of the species and ecosystems. Again, in this respect, we find convergences and divergences between the proposal of ecological consciousness and that of Christian social thought.

THE VALUE OF SPECIES AND ECOSYSTEMS

One of the crucial debates in philosophical anthropology revolves around the status of the human being in nature as a whole. What is it that distinguishes us from other forms of life? What makes us special? What legitimizes our lordship over other living beings? Thinkers who have asked themselves about the differential and distinctive aspects that give human beings a unique place in the history of the planet and, therefore, justify their privilege and authority to decide on other forms of life, conclude that it is consciousness, language and superior intelligence that have allowed the incredible technological development of Homo sapiens. This view of the human being is shared by most religious and philosophical traditions, as well as by many agnostic or atheistic thinkers. However, some philosophers and environmental activists have labelled it as anthropocentric. Moreover, this excessive claim, say the detractors of the dominant anthropological vision, is what has led us to the current situation of ecological bankruptcy, the disregard for other forms of life and the accelerated process of biological extinction in which we are immersed.

Expressed in another way, the question raised by ecological awareness is whether we should lower the human or raise the non-human, that is, in any case dilute the narrow distinction that our culture makes between those who are an end in themselves and possess intrinsic value (humanity) and those who are a means and possess instrumental value (the rest of nature). For much of the ecological thinking, this false dichotomy is the justification for our despotic actions towards other forms of life and the reason for the injustice we commit against them every day. The debate has been served up and the issue remains an academic battleground through which rivers of ink flow. In the case of Christian humanism, which has always defended the universal and inalienable character of human dignity, the question has been reformulated by drawing on tradition, the Bible and the

theology of creation.

Pope Francis avoided falling into anthropocentrism by speaking of a ‘sublime communion’ in which the human being, without losing their inalienable dignity, is part of a web of life that also has an intrinsic value: “We take these systems (ecosystems) into account not only to determine how best to use them, but also because they have an intrinsic value independent of their usefulness. Each organism, as a creature of God, is good and admirable in itself; the same is true of the harmonious ensemble of organisms existing in a defined space and functioning as a system. Although we are often not aware of it, we depend on these larger systems for our own existence” (LS 140). Taking the Bible, the Catechism, Christian thinkers and the Magisterium as references, Pope Francis insists: “we warn that the Bible has no place for a tyrannical anthropocentrism unconcerned for other creatures” (LS 68); likewise, “the Catechism questions, in a very direct and insistent way, what would be a distorted anthropocentrism” (LS 69).

However, and here is where it is vital to go slowly so as not to go from one extreme to the other and fall into the temptation of a subtle misanthropy, “a misguided anthropocentrism need not necessarily yield to ‘biocentrism’, for that would entail adding yet another imbalance, failing to solve present problems and adding new ones” (LS 118). In short, as usual in Catholic thought, the dilemma that the environmental crisis has highlighted is addressed by keeping the extremes in tension, just as sacramental theology does it by recognizing the created world as a sign or ‘sacramental’ of God, without confusing or merging it with the Creator. Quoting Pope Benedict XVI, Pope Francis recalls in this regard: “Christians, moreover, are called to accept the world as a sacrament of communion, as a way of sharing with God and our neighbours on a global scale. It is our humble conviction that the divine and the human meet in the slightest detail in the seamless garment of God’s creation, in the last speck of dust of our planet” (LS 9). Species and ecosystems have a value that goes beyond their instrumental use, a value that we need always to recognise and preserve.

References

Chief Seattle. 1855. Letter to President Jefferson of the USA. (http://www.csun. edu/~vcpsy00h/seattle.htm)

d’Eaubonne, Françoise. 1974. Le féminisme ou la morte. Horay, Paris.

Jonas, Hans. 1979. The imperative of responsibility: in search of ethics for the Technological Age. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Laurent, E. & Prochet, P. 2015. For a social ecological transition: what solidarity in front of environmental challenges? Les petits matins, Paris.

Martínez-Alier, J. 2005. El ecologismo de los pobres: conflictos ambientales y lenguajes de valoración. Icaria, Barcelona.

Pascual Rodríguez, M. & Herrero López, Y. 2010. Ecofeminismo, una propuesta para repensar el presente y construir el futuro. Bulletin ECOS n. 10. CIP-Eco-social, Available in https://www.fuhem.es/media/ ecosocial/file/Boletin%20ECOS/ECOS%20 CDV/Boletin_10/ecofeminismo_construir_futuro.pdf)

Pope Benedict XVI. 2009. Encyclical Letter, Caritas in Veritate. On integral human development in charity and truth. Vatican City. Pope Francis. 2015. Encyclical Letter, Laudato Si’. On care for our common home. Vatican City.

United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice. 1987. Toxic wastes and race in the United States: a national report on the racial and socio-economic characteristics of communities with hazardous waste sites. Public Data Access, Michigan.

Could the Pandemic Create a Less Exclusive Economy?

THE COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the global crises that were already there, the recognition of a dysfunctional economy and the driving force behind highly unequal societies—which favour new paths, fears and hopes, but the future remains unknown.