REFLECTIONS • CAMEROON

The Narrow Path To Justice And Reconciliation

There seems to be no quick solution to the internal conflict that has split the country since 2016. The Church appears unable to be a sign of unity. Yet the testimony of the late Cardinal Tumi remains alive. One of his heirs speaks

BY

Fr Ludovic Lado SJ

Interviewed by Fr Filippo Ivardi Ganapini MCCJ | Editor of the Comboni Magazine Nigrizia

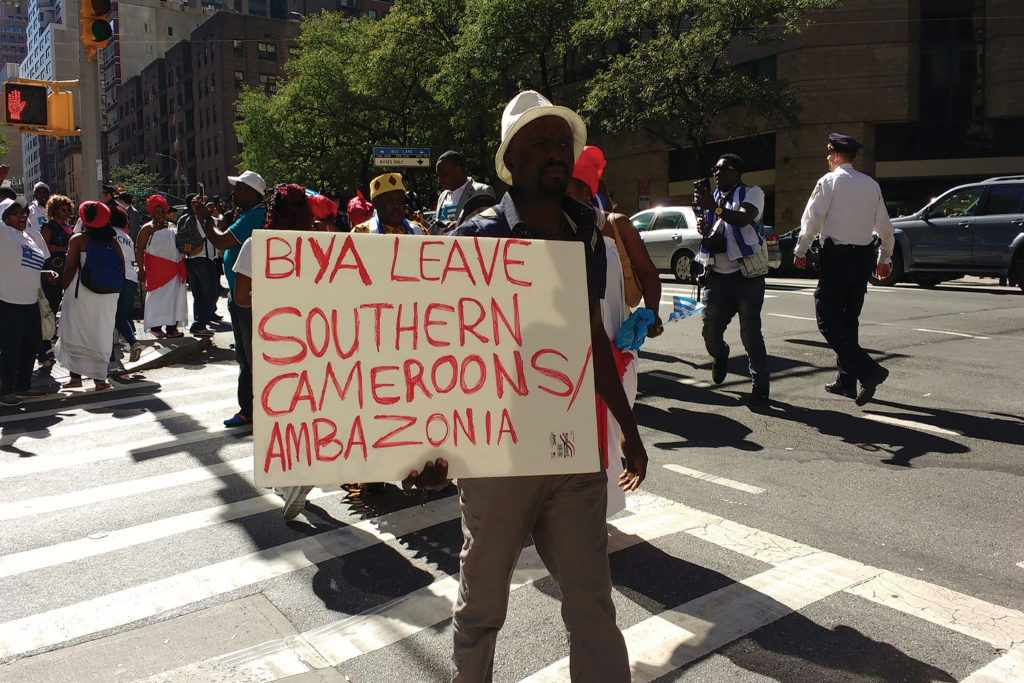

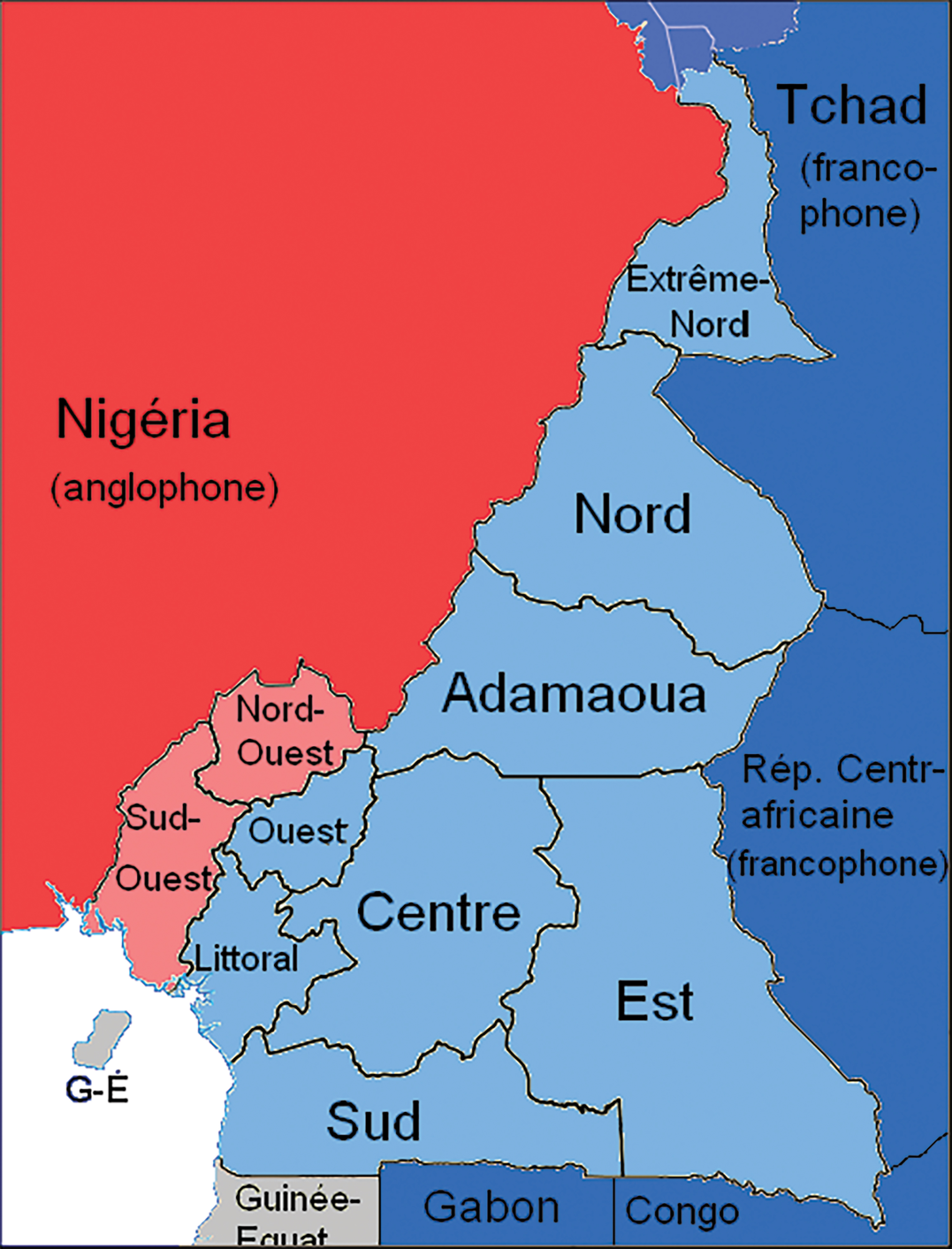

THE CONFLICT that erupted in 2016 in the English-speaking areas of the northwest and southwest of the country has its roots in the past. It goes back to 1961 when the formerly British Southern Cameroons joined with French Cameroun to form the Federal Republic of Cameroon. Ever since, the English-speaking minority felt marginalized and their right to autonomy was disregarded by the central government. For years, the northwest and southwest regions of the country have been campaigning for a continued use of the English language in schools and courts. When in 2016, the government dispatched French-speaking judges and teachers in the Anglophone region, people took to the streets to protest against it. The revolt was brutally repressed by the police force, resulting in the loss of many lives and the imprisonment of hundreds of activists. In the meantime, a separatist group started a guerrilla war for the secession of the Anglophone region and declared the self-proclaimed independent Federal Republic of Ambazonia. In the last five years, repeated armed raids by Anglophone rebels and the open conflict with the national army have claimed over 3 000 lives.

In such a climate of open confrontation, the Catholic Church in Cameroon has struggled to show herself steadfast as a bulwark of unity and an agent of reconciliation. She has shown quite clearly her internal differences. On one side, there are the bishops of the Anglophone areas who in their memorandum to the government have foreseen the risk of escalating violence and warned against the radicalization of the conflict. On the other side, sectors of the Catholic hierarchy, linked to the French-speaking area, have gone as far as supporting openly the repressive approach of President Paul Biya, in power since 1982. Some bishops, instead, in line with the thinking of Cardinal Christian Wiyghan Tumi, bishop emeritus of Douala who died last April at the age of 90, distanced themselves from the violent repression chosen by the regime against the opponents. Most of the ordinary people in the Church live in fear and prefer to be quiet and not to take any risk by exposing their socio-political views.

Aware of the Gospel’s demands for reconciliation, Fr Ludovic Lado, a Cameroonian Jesuit and a member of CEFOD (Center for Studies and Formation for the Development of N’Djamena-Chad), wants to bring his contribution to a divided country, helping the Church to become a sign and instrument of unity. In October last year he embarked on a pilgrimage from the city of Douala to the national capital Yaoundé. With his pilgrimage the priest wanted to encourage prayer for peace in the country, especially in the troubled English-speaking northwest and southwest regions. But after only two days of walking, Fr Lado was detained by the police who accused him of “an illegal activity on a public road”. Subsequently released with no charges filed against him, the Jesuit priest had to abandon his pilgrimage. Nonetheless he is determined to pursue the cause of justice and reconciliation in his country.

We contacted him on the phone asking him to take stock of his commitment.

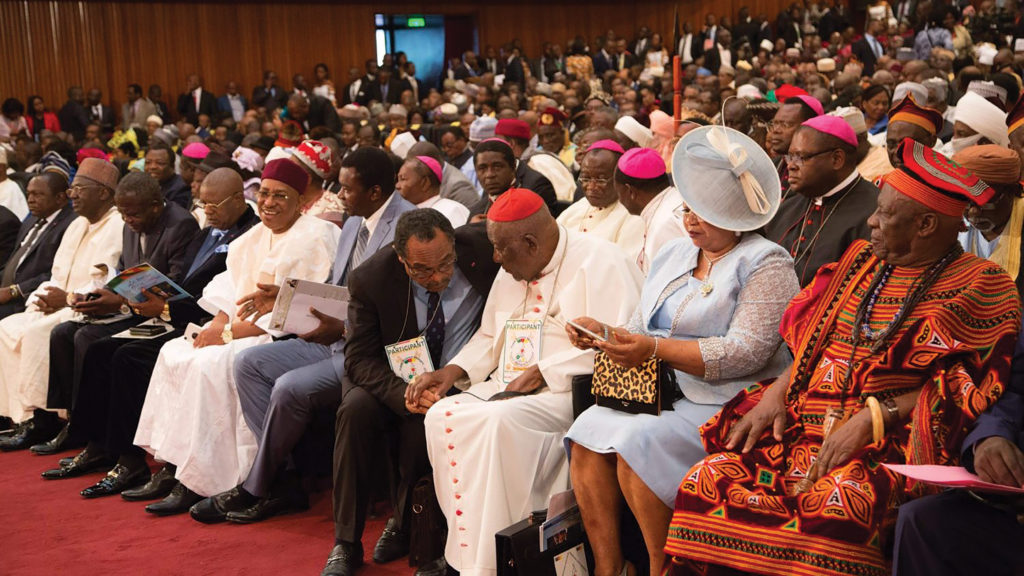

The crisis in the country seems to have no end with an increasingly marked division between the French and Anglophone areas. Do you see any glimmer of hope for a solution of the conflict after the National Dialogue was launched in October 2019?

The well-known National Dialogue, much boasted by the government but poorly organized, is not at all inclusive and has not resolved the Anglophone crisis. Arbitrary killings, armed raids against villages and kidnappings continue in Anglophone regions and the regional elections of last December, which saw little local participation, were nothing more than a parody of decentralization and democracy. The ruling party has centralized for itself all the most important posts for governing the country. The current regime has no far-sighted political vision for the country’s future and does not allow opposition from the various cultural, ethnic and linguistic groups to contribute to the common good. There is nothing more to be expected from this corrupt system and only the departure of President Paul Biya, in power for the past 39 years, will perhaps be a trigger for the change. Actually, it is the élites around Paul Biya who run the country and make the decisions for him. These very people have no intention of engaging in dialogue with minorities or embarking on a real path of reconciliation. What we have in Cameroon is a very corrupt regime, responsible for a massive embezzlement of public finances and set only on promoting its own selfish interests.

What steps do you foresee in order to start a process of change based on a national reconciliation?

Sooner or later a true inclusive national dialogue will have to be organized with the more dynamic forces in the country, but I seriously doubt that this will be possible before Paul Biya leaves power. Those who are at the top now only know the language of violence to safeguard their interests and share the spoils of the state. To help heal the wounds, it will be necessary to envisage a long path of truth and reconciliation. The road is going to be long and painful because the wounds, especially on the English-speaking side, run very deep.

You started a peace march that was interrupted. Are you going to re-launch it and with what objectives and methods? Or are you thinking of other ways of bearing witness to the quest of justice and peace? What role should the Church play in resolving the conflict?

No, I do not think that I will re-launch the march unjustly interrupted by those in power. The message has reached the people. All I wanted to do was to draw attention to a general indifference that hinders the duty of brotherhood. I remain convinced that the Church could have done better to help resolve this crisis, but the infighting for leadership within the Cameroonian episcopal conference, has hindered the mobilization of the people against the oppressive policies of the state. I am currently writing a book based on the stories of suffering and resilience of about fifty internally displaced people due to the Anglophone crisis. Proceeds from the sales of this book will be used for the schooling of internally displaced children. I hope to find the necessary means for its publication.

Cardinal Christian Wiyghan Tumi, recently deceased, was a true witness of the gospel of peace and he influenced the generation of Catholics that has taken the side of justice and the poor. What is his most important legacy that he left to us?

Cardinal Tumi leaves a rich legacy to the Cameroonian Church and society. He was a man of God who loved justice and freedom, a very human person who was able, with his commitment, to bridge the gap between English-speaking and French-speaking Cameroon. He fulfilled his role as pastor and citizen by demonstrating that one does not exclude the other. He died without being able to see true democracy in Cameroon and the solution to the Anglophone crisis.

Do you see other witnesses or prophetic signs in the Cameroon Church today?

There are certainly Christians who dare to engage in prophetic gestures, some with discretion, others more openly. By and large, the Church in Cameroon is more concerned about rituals than to involve herself in prophetic actions. She is plagued and weakened by the same identity divisions that shatter Cameroonian society. Lay people are very afraid to engage themselves in actions that denounce injustices. They prefer to be concerned with liturgical rituals instead of becoming involved in the demanding work of Justice and Peace Commissions to build a truly free society.

What could be done in Cameroon so as to put into practice Pope Francis’s encyclical Fratelli tutti?

The encyclical of Pope Francis calls for a personal and collective conversion to the gospel of universal brotherhood. To do this as Christians we must feel challenged every time that the dignity of our brothers and sisters in the English-speaking areas is being trampled upon. In a document, inspired by Fratelli tutti, that I published on the eve of my pilgrimage for peace, I ask: “Where are our brothers and sisters from the northwest and southwest? Some have died, often in atrocious conditions, others are displaced in the countryside or have fled the country. Most have remained in those regions where their dignity is daily tested by precariousness”.