CHALLENGES • MISSION IS COMMUNICATING LIFE

in a shopping centre in Alexandra township, Johannesburg,

South Africa, 12 July 2021. Picture: Yeshiel Panchia.

On Riots, The Pandemic And Doing Theology

“The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear” (Antonio Gramsci)

BY Archbishop Thomas Menamparampil, SDB | Archbishop Emeritus of Guwahati, India

The Italian author Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) wrote these words from prison in around 1931. Many of us might well imagine he was writing from South Africa ninety years later!

We are living in troubled times in South Africa: the Covid pandemic and the haphazard way in which vaccine delivery is happening; growing poverty and unemployment, accentuated but by no means caused by the pandemic; ongoing political corruption and mismanagement of public resources, with highly uneven—some might say half-hearted—attempts to fight it. We are seeing the ruling African National Congress deeply divided within itself, possibly in the process of fragmentation, over the very crises I have mentioned. The recent traumatic and violent protests and looting in KwaZulu Natal and Gauteng, the worst since the 1994 democratic transition, seem to mirror the morbid symptoms I have described above. The riots—and the wider crisis in which they occurred—demand serious political and ultimately theological analysis.

Why did the riots happen? There are three possible reasons (or combinations of the three):

1. Poverty and discontent;

2. A reaction to the Covid crisis;

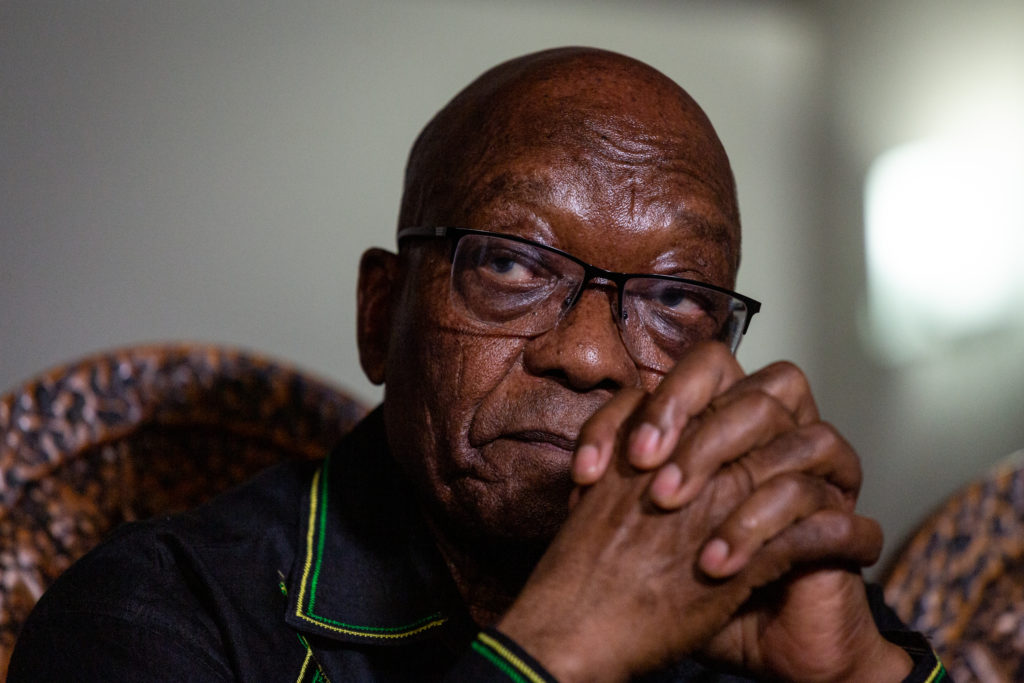

3. Political maneuvering precipitated by Jacob Zuma’s imprisonment for contempt of court.

Let us examine these.

First, poverty and discontent. This line of thinking suggests that they happened because of the general state of poverty and unemployment in South Africa, a state worsened, but not simply caused by the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, lockdown and rising unemployment caused by the lockdown. On a prima facie level this sounds credible. Historically, there are connections between disasters—be they famine, plague or some kind of natural occurrence (e.g. earthquakes, floods etc.). If that were the case, we should have experienced the riots across a wider territory than actually occurred. They should also have happened sooner rather than later, arguably during the toughest period of lockdown back in 2020.

Moreover, the conditions—poverty, unemployment and discontent—have existed in South Africa for much longer than 2020. Granted, the Covid lockdown caused a spike in unemployment—and highlighted the socio-economic disparity more intensely than ever before: wealthier people have been able to ‘sit out’ the lockdown better, have had (relatively) easier access to cash reserves to tide themselves over in some cases, or the resources to move their work from office to home. However, it seems odd that the riots themselves were on the whole highly localized, mainly in two provinces. Indeed, some of the poorest regions of South Africa (where one might assume poverty would precipitate violence) did not on the whole, participate. So, on a balance, I would see this factor as contributing in part to rioting and looting and not as its primary cause.

in some industries such as hospitality and alcohol.

Photo: Silverton, Pretoria. Credit: Worldwide.

What of reaction to Covid-19 itself, our second factor? Historical precedents exist. In the past, times of plague have precipitated protests and mass movements, many of them articulating some kind of belief that the end of the world was nigh. Often these movements were linked to beliefs rooted in defective reading of apocalyptic religious literature like the Book of Revelation and the conviction that plague was divine judgment for the world’s sins. But this has not happened significantly during the global Covid pandemic (nor indeed did it during the Great Influenza epidemic one hundred years ago). Granted, there has been a considerable undercurrent, including in South Africa, of what might be called ‘Covid denialism’ and protests about precautionary restrictions, but compared to many countries, this has not happened as much here. Though there have been objections to occasions of police heavy-handedness in enforcing things such as curfews, I have found little or nothing of this rhetoric surrounding the 2021 protests.

There was no general uprising, just localized resistance in areas where Zuma has support

Similarly, I have no sense from what I’ve heard or read that the protests can be traced to a kind of kneejerk reaction by people against being cooped up by the lockdown—or indeed, as I mentioned, a protest against the serious economic side effects of the lockdown.

One is therefore left with the third, and to my mind, most credible cause: reaction to the imprisonment of former president Jacob Zuma for contempt of court. The evidence supporting this claim seems overwhelming. His allies in the ANC warned that if Zuma was jailed there would be protest: it happened. Although the case is by no means closed, there is mounting evidence that the protests (and subsequent looting) were encouraged—if not actually organized—by members of Zuma’s inner circle within the ANC. Beyond that, I have heard people say that when the rioting and looting started, those involved were in effect bussed into the areas affected (local people may then have joined in out of purely material self-interest). There may also be an element of trying to warn the state not to go after other members of Zuma’s cronies implicated in corruption.

More interesting is the question why this was done. It is conceivable that (assuming the organized protest claim is true, which at least seems the case) that it was simply a show of force to get Zuma released. Historically, protest actions—particularly strikes—have often proven effective in the past (at least since 1994). Simply put, and all morality aside, violence works. State counter-violence in these cases has tended always to backfire on the state; shooting protesters and strikers has all too strong a resonance with the apartheid era, even in cases where the first acts of violence were committed by protesters themselves.

is an issue of great concern for many citizens in South Africa.

Photo: Orange Farm, Johannesburg. Credit: Carla Fibla.

Credit: Brigitte Moshammer/Pixabay.

A deeper possible reason for the ‘organized resistance’ claim could even be proposed: the first step to overthrowing the government of Cyril Ramaphosa and ‘restoring’ Jacob Zuma (or a close ally) to the presidency. The idea of a general strike or mass uprising has historical precedent (e.g. Russia in 1917), as has the idea of ‘rolling mass action’ in South Africa’s history. If this was in the minds of Zuma’s cronies—whose position within the ANC may be slowly weakening as public sentiment increasingly turns against government corruption and inefficiency, closely associated with the Zuma faction—they miscalculated. There was no general uprising, just localized resistance in areas where Zuma has support. Similarly, despite appearing ‘weak on crime’, Ramaphosa reigned in the temptation to violently suppress the protests—an act that could have played into Zuma’s hands. In short, if this was a power play on the part of Zuma and friends, it backfired dismally, despite the heavy cost in lives and to the economy.

What theological insights, if any, can we derive from these events, particularly how we as Christians can contribute a useful and sound moral voice to current events? I cannot in a short article here express this as fully as it deserves, but I hope to present a few points that we shall all have to work on.

Our theology must find a way of building dialogue with secular ideas and practices of governance

First, we can no longer afford to frame our moral reflections and witness in simplistic, ‘bi-polar’ terms. We no longer live in a society where there is a clear ‘villain’ like apartheid and equally an obvious ‘hero’ or ideal like democracy. Even issues in the deep background to the recent protests—poverty and inequality—offer no simple solutions. History teaches us that simplistic redistribution doesn’t work—and the protagonists who propose such solutions to varying degrees (notably the Zuma faction and the far left) have themselves a less than salubrious track record, suggesting that even if it were feasible, such radical economic transformation would ultimately serve another elite. In like fashion, both romanticized protest and the sanctification of repressive force to ‘preserve’ society don’t work. We need as Christians to develop a more nuanced theology of protest and what might be called (echoing the sociologist Max Weber) a ‘theology of legitimate state force’ to deal with both ambiguities and the real possibilities of excessive and illegitimate protest and/or state violence.

This proposal might unsettle some of you. After all, surely Christians must embrace nonviolence as a moral absolute? Quite frankly, I believe that though it is an ideal to which we must all strive, it is impossible for Christians in public life not to face the ugly reality of force. When we were a marginal sect awaiting the Second Coming, perhaps it was possible; once Christians took their place in the public square we had no choice than to accept the possibility of force. What we are called to do is to struggle to limit force as far as possible—and through our teaching to inculcate in citizens (most of whom are Christians) the need to do likewise.

Second, more importantly, we as Christians must deepen our commitment to and reflection on such tools that make democratic civil society possible, notably the rule of law and the need for it to be upheld fairly and equitably to all. If my analysis is correct, the recent crisis and violence was precipitated by a refusal of certain individuals and groups to accept the idea that all citizens, no matter how famous or highly regarded for their alleged contribution to society, are subject to the same laws, the same procedures, and the same penalties for violating them. Perhaps this can be summarized theologically as the need to develop a ‘theology of due process’. This is in itself part of a wider theology, a theology of civil society and democratic governance.

Here too we need to build upon what already exists and renew it in the light of new circumstances. Many of us in the past embraced theologies of liberation and struggle—in South Africa from the 1980s onwards it was called Contextual Theology. It, together with more mainstream theologies such as Catholic Social Thought, served us well and brought us to the (however flawed) democratic transition of 1994, but the context has changed and our theology must change with it.

Such a new theology must of necessity take account of the fact that the modern state is secular and independent of Church ‘control’, even in situations where many (indeed most) lawmakers and administrators are Christian. Our theology, and the theologies of other faiths, must find a way of building dialogue with secular ideas and practices of governance. It is worth noting here, for religious people filled with unease at the prospect, that many observers would claim that modern secular democracy is the non-religious expression of values first articulated in religious language, in one sense the ‘agnostic child’ of religious, mostly Christian, parents.

Third, our social analysis—upon which we build our theological responses to developments and crises around us—must be more subtle, more ‘scientific’, in the sense that we must use the best available knowledge at our disposal. Crude analyses—particularly simplistic splits between rich/poor, black/white, and even ‘us’/ ‘them’—yield data that is at best flawed, at worst utterly useless. There’s an old maxim: rubbish in, rubbish out—or, as they say in the field of medical research ethics, bad science is bad ethics. Our theological and moral reflection in every area including public life must reflect good (as opposed to myopic) ways of Seeing, so that our theological Judgment is sound and constructive, on which to build more effective Action.

To conclude, I think we must admit that for the most part the religious communities of South Africa dealt with the recent protests and looting rather poorly. We messed up because our analysis of the situation was weak, our theological reflection at best second hand, outdated or simply nonexistent. Will we do better next time? (Yes, there will be a next time—even next times). Perhaps we should revisit the words of Jesus (Mark 2: 22) in this regard:

“And no one pours new wine into old wineskins. Otherwise, the wine will burst the skins, and both the wine and the wineskins will be ruined. No, they pour new wine into new wineskins.”