PROFILE • MISSIONARIES IN SOUTH AFRICA

Photograph: Fr L.A. Mettler, Congregation of the Missionaries of Marianhill (CMM).

A Missionary Ahead Of His Time

Abbott Pfanner was a pioneer of the evangelization in South Africa, adapting monastic rules to mission work. He believed in equality and integration, and worked tirelessly with his companions to give young Zulu boys and girls educational opportunities, both academic and vocational

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

ST DANIEL Comboni’s famous motto was ‘Save Africa with Africa’. In the middle of the 19th century, this was a uniquely progressive proposal. In practice, it meant taking the Gospel to Africans who had not heard it before—and preparing them to then evangelize their own people. Missionary work was not, Comboni believed, uniquely for white Europeans.

Even at the end of that century, various factions of the religious establishment still did not accept such revolutionary ideas. As for adapting the way that missionaries operated in order to take the Gospel to the people in the best possible way, some aspects of that certainly did not go down well—as Abbot Franz Pfanner learned to his cost.

Pfanner was far-sighted enough to understand the importance of education, of health, of sustainable employment, and even of promoting the role of the laity

Criticism of Abbot Pfanner’s way of working came from both clergy and laity—and perhaps prefaced the more cruelly divided society that emerged in the 20th century in South Africa. Bishop Charles-Constant Jolivet, then Bishop of Belline, was reported as saying that it was a mistake to give “too much” to the black people because that would make of them “bread Christians”. A letter published in a Natal newspaper accused the Trappists (of whom Abbot Pfanner was leader in South Africa) of “seducing the natives” through their kindness in order to convert them and bring them to submission.

What was it that alarmed people about the Trappists’ approach to their missionary work? That the world’s largest monastery, founded by Abbot Pfanner, was too ostentatious? That the Trappist Rule was not being observed properly in the efforts to reach out to mission stations? or simply that people of all faiths and none, were accommodated by Pfanner’s idealism?

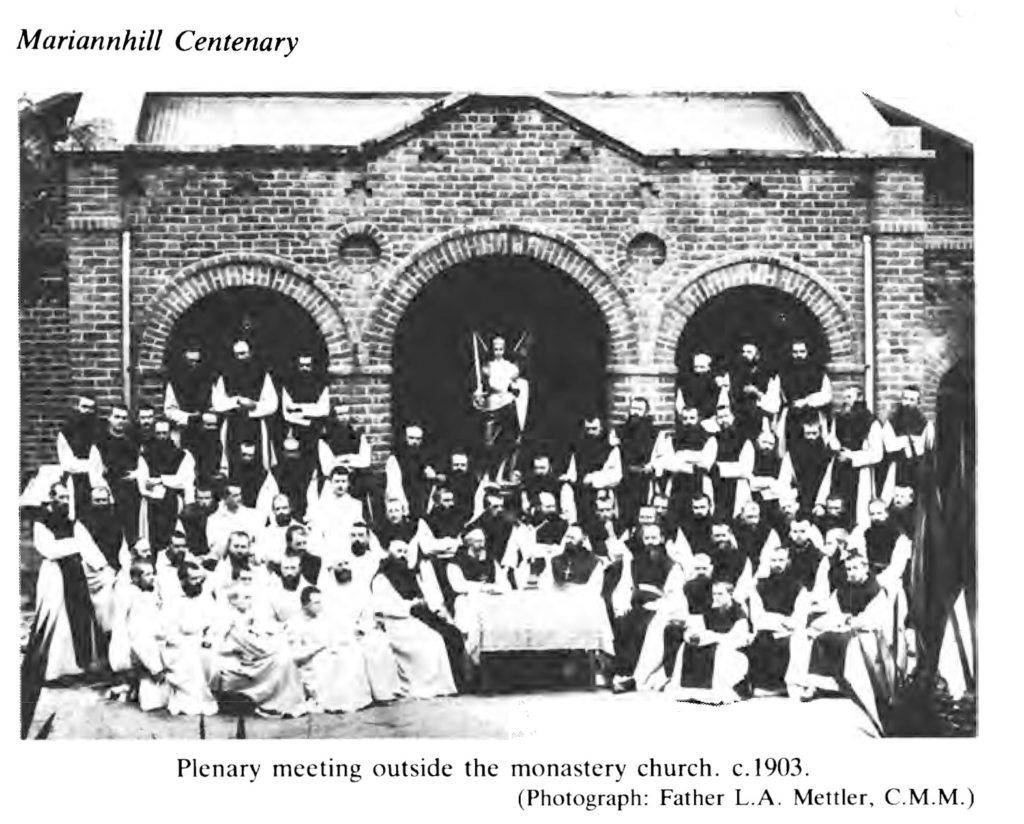

The establishment questioned the Austrian-born Abbot and found him wanting—but his legacy is the beautiful Mariannhill Monastery, which he established on the periphery of Durban in 1882 and which continues to flourish. Both Comboni and Pfanner seem to have won the day, if the photographic evidence is anything to go by. A plenary meeting pictured at Mariannhill in 1903 shows a sea of white faces. Move on some 120 years and the men photographed for the Mariannhill website are predominantly black.

Just as Daniel Comboni aimed to save Africa with Africa, Pfanner’s ideal was to promote the integration of the indigenous Zulu people in the white society of the then Transkei region. He was far-sighted enough to understand the importance of education—for girls as well as boys—of health, of sustainable employment, and even of promoting the role of the laity.

For all of this, the gaunt man with the long beard was censured.

Where had his ideas developed? What turned a red-haired boy who teased his contemporaries in the village of Langen, near Bregenz in Austria, where he was born on 21 September 1825, into a missionary with what was seen by some as too much zeal?

Trappist with a missionary call

Abbot Pfanner’s birth name was Wendolin and his twin brother was Johann. Johann from the outset seemed the one who would follow in the farming footsteps of their parents, while Wendolin was clearly a scholar, winning prizes and going on to university. His post-graduate course in philosophy at Padua University in northern Italy was, however, put on hold when he fell ill and was confined to a sanatorium. Some say he suffered from pneumonia and meningitis, others that tuberculosis was the root cause of his illness—and certainly, having been raised on a farm where he would have consumed unpasteurised milk, TB is most likely to have been an underlying condition.

God, moving as always in mysterious ways, chose this moment in Pfanner’s life—lying in a sanatorium with weakened lungs—to inspire him to be a missionary. It seemed impractical, but he began the process by studying for the priesthood and in 1850, at the age of 25, he was ordained. Despite succeeding in his work in a problematic parish, his bishop turned down his request to fulfil his calling to missionary work and instead posted him to a convent in Croatia—neighbouring on northern Italy—to oversee the nuns there. Another success story, but again, his health let him down and he had to take time off to recover.

It was then that he sought to join the Trappist Order, officially the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, which demands hard manual labour, silence, a meagre diet, isolation from the world, and renunciation of most studies. This request from a priest who was passionate about evangelization was a strange one, but apparently, Pfanner believed he was destined for an early death and that joining the Trappists would prepare him for this. The bishop was doubtful, but eventually agreed to send Pfanner to the Trappist Mariawald monastery in western Germany. It was there that Wendolin became Franz, taking the name—as Pope Francis would do in the 21st century—of St Francis of Assisi.

Fr Franz, as he now was, recovered his health under the regime of the Trappists—the hard labour and vegetarian diet suited him. Ironically, as it turned out, his over-enthusiasm for the strict rules upset his confreres and he was ordered to leave Mariawald and set up a monastery elsewhere. He travelled to the Holy Land and to Rome, but in time it was at Banja-Luka in Bosnia that he set up the monastery of Mariastern: Star of Mary.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, his verve soon saw him create a mill, a fruit-drying plant, bridges and roads, a school and an orphanage. The monks were not allowed contact with females, but Pfanner solved the problem by introducing Sisters to teach at the school and orphanage. With hindsight, this seems like a blueprint for the work he would do in South Africa. The frequent tolling of bells (Pfanner had smuggled bells into Bosnia, which did not allow bell ringing, to call brothers to prayers) upset the neighbours as the monastery lands expanded to meet the Trappists’ need for self-sufficiency. This led to the first official rebuke—the bishop who received the complaints told him to curb his “unruly spirit” and limit further development. Moreover, in a strategy we have seen develop in industry in the intervening years, Pfanner was moved sideways by way of a promotion. Appointed Abbot, he was no longer in a position to be in the thick of the hard labour and the promotion of self-sufficiency.

A new mission in South Africa

Or so his superiors thought. He still wanted to be involved in missionary work, and when at a meeting of the Trappist Order, Bishop James David Ricards of the Eastern Vicariate in South Africa asked for monks to open a mission station at Dunbrody in the Eastern Cape, it was Pfanner who responded: “If no one will go, I will go.”

The offer was accepted, and Abbot Pfanner and a group of monks were soon sailing to South Africa. It was not, of course, an easy journey, and the location of the mission station was unwelcoming, but the “hard manual labour” ethic kicked in and the men cleared the land to achieve their aim of self-sufficiency. They had brought with them a printing press, and Pfanner used this to create fund-raising leaflets to send back to Europe. Despite the debilitating seasickness he knew he would experience, he went on fund raising missions to Europe, making the kind of compelling addresses that brought in the cash needed for the work in South Africa. The vow of silence did not seem to get in his way—and it is said that he never let such “man-made” rules get in the way of God’s work.

Those funds that were raised were not, however, used for the Eastern Cape project, where drought persisted. Pfanner asked, then, Bishop Jolivet in Natal if he could take his mission to that diocese. Could turning down the area the bishop suggested have set Jolivet against Pfanner’s future projects? Instead, he successfully bid for a farm that was up for sale near Pinetown and moved the whole operation there by rail and ox-wagon, arriving in December 1882.

And there, on 26 December, this Trappist missionary with his visionary ideals established Mariannhill Monastery on the edge of Durban. He intended to promote the integration of the native Zulu people into white society by opening schools, health clinics, craft workshops, printing presses and farms providing work for hundreds of monks, lay missionaries, nuns and natives. It was a whole new approach to missionary work in South Africa. An approach that opened up aspirational horizons for a rural community; that gave young black boys and girls, men and women, educational opportunities, both academic and vocational.

The monks began building work and farming that called on their own manual labour—that core Trappist tenet. They set up the first school—again bringing in nuns to teach the girls—and they taught a range of trades as diverse as carpentry, bookbinding, printing and tailoring.

Mariannhill Abbey

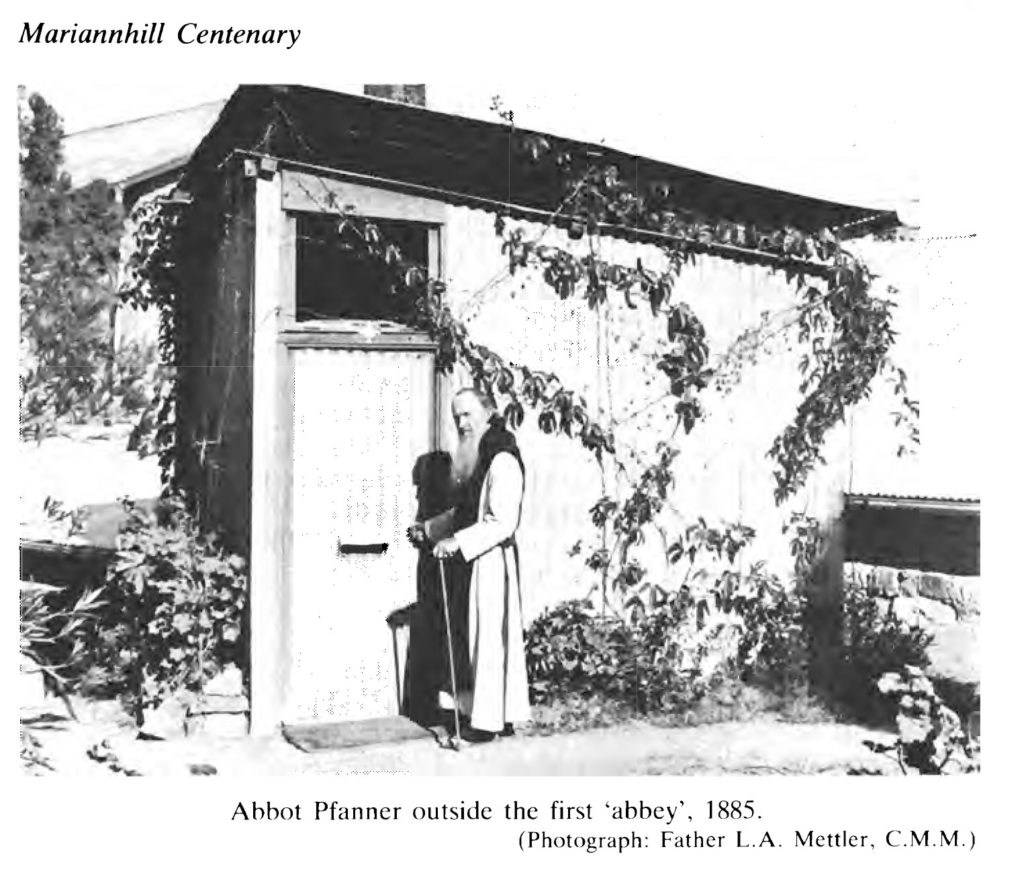

Almost miraculously, by 1885 the magnificent building that is the Mariannhill Monastery was not only up and running, but given abbey status, with Pfanner appointed as its abbot. For him, this was just the start. Throughout the 1880s, he spread the Word by building a network of mission churches throughout southern Natal. Each was built on a farm that could sustain clergy and laity alike.

If that sounds exciting and ahead of late 19th century thinking, consider this from Pfanner: “All boys in our institute receive free bed, board, and instruction, regardless of whether they are pagan, Muslim, Protestant, or Catholic, white, black, or coloured, English, Dutch, German, Italian, Indian or local African.”

Pfanner wrote in 1890 in his Principles for Mission that the aim of Marriannhill was “to pursue and bring about an equal status for black and white people”

This 19th century Francis was laying down the ideas that our 21st century Francis has expressed in Fratelli Tutti—that we are all brothers and sisters; that no one should be marginalised; that all are equal.

Pfanner wrote in 1890 in his Principles for Mission that the aim of Marriannhill was “to pursue and bring about an equal status for black and white people”. He would have been deeply disillusioned by how that worked out in the 20th century—and surely greatly saddened that in the third decade of the 21st century there is still a desperate need for the ‘Black Lives Matter’ campaign.

Under scrutiny

Of course, he may have had an inkling how things would progress. Although by 1887 he had sent the first Mariannhill candidates to Rome to study for the priesthood (and the first Zulu Catholic priest would be from Mariannhill); although supporters in Europe appreciated his work sufficiently to send generous donations for his work; although his outreach scheme was so obviously a success, Pfanner was under scrutiny because he was failing to follow the Trappist Rule. To enable continued success, he asked for the rules to be changed—to officially allow Zulu-speaking novices to teach at outlying missions, Sisters to teach girls in the schools, extra food given to sustain the hard-working brothers. He even distorted the description of Mariannhill, trying to get round the difficulties—it was not a mission, he suggested, but a base for missionary activity. But underlying this are those comments from Bishop Jolivet, that snide letter in the newspaper. Was this all about attempted integration rather than Trappist rules?

An inspection of his work resulted in Pfanner’s suspension. He spent that year in Lourdes in the Eastern Cape and offered his resignation, which was turned down. Meanwhile, all the dispensations he had put in motion were reversed and outreach stopped. In 1893 at the age of 70 he moved to a farm near Lourdes for a new life.

Perhaps not entirely new. He spent his time there drafting a statute for a new missionary society, to be responsible directly to Rome, adapting Trappist rules to be compatible with mission work. Mariannhill liked his ideas, but not until February 1909 would Pope Pius X approve the separation of the Mariannhill Missions from the Trappist Order. That approval allowed Pfanner to die in peace just three months later—and also allowed Mariannhill Missions to spread, taking the idea that we are ‘fratelli tutti’ around the world.