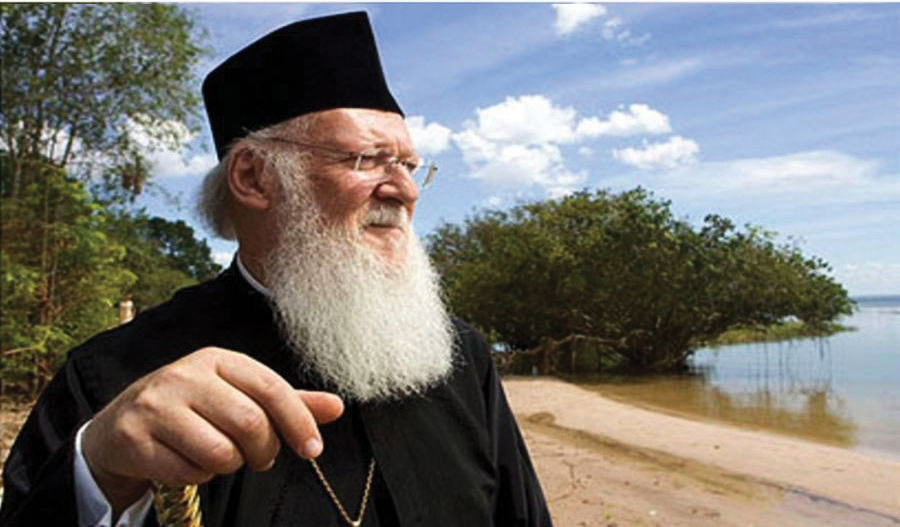

PROFILE • BARTHOLOMEW, THE GREEN PATRIARCH

Source: Jindrich Nosek (NoJin)/commons.wikimedia.

A PIONEER IN THE CARE FOR CREATION

In his long-serving ministry, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew has unreservedly committed himself to the protection of the environment and the cause of peace, justice and unity among all peoples, ceaselessly calling for effective solutions to the climate emergency

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI, SCOTLAND

INTERGENERATIONAL INJUSTICE. It’s a phrase we will hear more of in reaction to studies such as the one entitled, Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes by Wim Thiery, among a large number of international scientists, published in the journal, Science in September 2021. According to it, children born in 2020 will endure, in their lifetime, an average of 30 extreme heat waves—seven times more than someone born in 1960—, twice as many droughts and wildfires, and three times more river floods and crop failures than someone who is 60 years old today. They will experience all this even if countries fulfill their current pledges to cut future carbon emissions. Intergenerational injustice indeed. The study also affirms that only those under 40 years old today will live to see the consequences of the choices made on emission cuts. Those who are older will have died before the impacts of those choices become apparent in the world.

Vision for the future

There’s a proverb that says ‘A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they know they shall never sit.’ Some attribute it to the Ancient Greeks and has certainly been much quoted and adapted by everyone from Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore to a plethora of 21st-century social media philosophers. This seems an apt response to the disturbing summary of what our choices in reaction to the climate emergency must be.

The proverb—and the study—certainly would be well understood by His Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, the 81-year-old spiritual leader of the world’s 300 million Orthodox Christians, known worldwide as The Green Patriarch.

In harmony with Pope Francis, whose Laudato Si’ document has become a road map for the ecological changes needed to conserve our common home, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew said: “The world is not ours to use for our own convenience. It is God’s gift of love to us, and we must return His love by protecting it and all that is in it.”

Protection of the common good, of the integrity of the natural environment, is the common responsibility of all the inhabitants of the earth.

To be very blunt, neither the Pope nor the Patriarch will live to see the benefits of the ecological campaigns they have initiated. Their faith tells them that we must act now if we are to halt intergenerational injustice, cutting emissions that will lead to the climate extremes that already affect livelihoods, food security, and peace itself.

Published in 2011, and edited by John Chryssavgis, the third volume of Patriarch Bartholomew’s writings, On Earth as in Heaven: ecological vision and initiatives of Orthodox Christianity and contemporary thought is an engaging vehicle that brings together his statements on environmental degradation, global warming, and climate change. It is surely worth emphasising that date—published in 2011. These were not new writings, but those covering the first two decades of his ministry. Too many have taken too long to catch up.

Prophet of ecological conversion

In May 2011, the Green Patriarch, wearing his ‘ecumenical’ hat, asked Churches to reflect on God’s love for the world, saying of weapons of mass destruction and of the climate crisis:

“Our present situation is in at least two ways quite unprecedented. Never before has it been possible for one group of human beings to eradicate so many people simultaneously, nor has humanity been in a position to destroy so much of the planet environmentally. We are faced with radically new circumstances, which demand of us an equally radical commitment to peace”.

on 15 March 2019, drawing an enormous crowd estimated at 40 000 people, the vast majority being school students.

Source: John Englart/ Flickr.

This is a religious leader who is certainly no Johnny-come-lately to the issue of climate crisis. He has not jumped on the bandwagon as it trundles towards COP26, the conference seen to be the Last Chance Saloon for making changes that could save our common home. He has been talking and writing about this crisis for a very long time, and so is internationally recognised for his vigorous leadership on environmental issues. Moreover, he has not confined himself to theological arguments, but has raised the ethical aspects of the way the crisis must be addressed and offered practical solutions.

Of course, some people have been listening. In 2002, he received the Sophie Prize for his work on the environment, and in April 2008, he was included on the Time magazine list of the 100 most influential people in the world. Perhaps just not the right people have opened their ears. Those who exploit the planet and kid themselves, and the rest of us, that carbon off-setting schemes are ethical and effective, are still incredibly reluctant to take on board the realities presented by the scientists, the Green Patriarch, and Pope Francis.

of climate change. Istanbul, November 2009.

Credit: The Elders/Jeff Moore.

Since the Patriarch was unable to attend the talks leading to the Paris Agreement during the COP21 in December 2015, his ecumenical prayer for the preservation of creation was read in Notre Dame Cathedral by his eminence, Metropolitan Emmanuel of France. The Paris Agreement was adopted by 196 Parties (President Donald Trump would later withdraw the US signature).

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, emphasising not only his agreement with Pope Francis on the issue of climate change, stressed that his words, were not just for the political leaders gathered in the French capital, but offered as “an essential spiritual commitment”. He said: “the way we treat nature and the biodiversity of creation is directly related to the way we treat our neighbour.”

If the situation was dire in 2015, it would become even more catastrophic in the next six years that bring us to this year’s COP26. With truly prophetic words, he reminded his audience the need to address the reality that: “…creation is a gift that was given to us freely and we will be held accountable, not only to the future generations but also to the Creator God who placed it in our hands. The future of humanity will remain uncertain for as long as we are collectively unable to choose the common good”. He added: “The multiple crises affecting the world today act like the distorting prism of our own irresponsibility. Environment is a whole that goes beyond the safeguarding of wildlife and flora. It is also a question of justice, solidarity, fraternity, the constituent element of a humanism that needs to be rediscovered. As the prophet Micah wrote:

‘…what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God? (Micah 6: 8)’.”

Such powerful words—words to be expected from this man who ascended to the Ecumenical throne in November 1991 and immediately proceeded to work on his vision for a spiritual revival, Orthodox unity, Christian reconciliation, interfaith tolerance and co-existence, protection of the environment and a world united in peace, justice, solidarity and love.

Tolerance from Asia Minor

Coming from Turkey—that country on the edge between East and West—he perhaps was imbued with that spirit of tolerance, that desire for reconciliation, from his earliest years. Born on 29 February 1940 on the Aegean Island of Imvros, he was christened Demetrios by his parents, Christos and Meropi Archontonis. Is it too fanciful to imagine that he was exposed to philosophical debate from an early age in his father’s barber and coffee shop environment—those spaces where men put the world to rights?

He studied in Imvros and Istanbul, then graduated with honours from the Theological School of Halki in 1961. He was ordained to the Holy Diaconate that same year at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Imvros and given the name Bartholomew. However, for the next two years he was obliged to fulfil his military obligation in the Turkish army reserve.

He received his doctorate in Canon Law in 1968 from the Pontifical Oriental Institute of the Gregorian University in Rome before studying at the Ecumenical Institute in Bossey in Switzerland, and at the University of Munich, where he specialised in ecclesiastical law. Perhaps with this background, it isn’t surprising that Patriarch Bartholomew is fluent in Greek, English, Turkish, Italian, Latin, French and German.

When he returned to Constantinople in 1968, he was appointed assistant dean of the Sacred Theological School of Halki and the following year was ordained to the Holy Priesthood. Six months later, he was elevated to the office of Archimandrite in the Patriarchal Chapel of Saint Andrew.

Under Ecumenical Patriarch Dimitrios, he was appointed director of the Patriarchal Office, and on Christmas Day, 1973, Fr Bartholomew was consecrated a bishop and named Metropolitan of Philadelphia in Asia Minor. He remained as head of the Personal Patriarchal Office until his enthronement as the Metropolitan of Chalcedon in 1990. That same year, as Metropolitan Bartholomew, he accompanied Patriarch Dimitrios on a historic 27-day visit to the United States as his chief advisor and administrator.

Vocation to ecumenism

During this steady career path, he had been a member of the World Council of Churches Faith and Order Commission, acting as vice president for eight years. In January 1991, Metropolitan Bartholomew led the Orthodox delegation at the Seventh General Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Canberra, Australia. There, he framed Orthodox objections that the World Council was departing theologically from essential Orthodox beliefs —but that has not detracted from his strong advocacy for maintaining extended contacts with other Churches.

The way we treat nature and the biodiversity of creation is directly related to the way we treat our neighbour

These achievements meant that on the death of Patriarch Dimitrios on 2 October 1991, it was no surprise that Metropolitan Bartholomew was unanimously elected Archbishop of Constantinople, New Rome and Ecumenical Patriarch. There followed what reads like a ceaseless round of visits abroad and meetings with religious and political world leaders. And perhaps because the Ecumenical Patriarchate has that very special geographical and spiritual position between East and West, Patriarch Bartholomew has been able to nurture dialogue amongst Christianity, Islam and Judaism, and has extended the hand of spiritual friendship to the Far East, visiting China and Hong Kong.

A peace builder

Patriarch Bartholomew has been a trail blazer in terms of interreligious dialogue. Contributing to reconciliation in the Balkans, addressing issues of terrorism, and negotiating in countries such as Iran by addressing their governments on subjects of concern—in 2002 he spoke to Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs on “The contribution of religion to the establishment of peace in the contemporary world.”

Today, he and Pope Francis seem to be leading the world in their unremitting efforts to bring about effective solutions to the climate emergency. They sing from the same hymn book, with the Green Patriarch stressing that the ecological problem affects all humankind, and above all has a painful impact on the poor and the weak.

The world is not ours to use for our own convenience. It is God’s gift of love to us, and we must return His love by protecting it and all that is in it

Speaking this year on the World Day of Creation (a day initiated by Bartholomew’s predecessor in 1989 and adopted by Pope Francis in 2015), he said, “Protection of the common good, of the integrity of the natural environment, is the common responsibility of all the inhabitants of the earth”. However, given the failure of political leaders to make decisions for the good of the environment, he asked, “How much longer will nature endure the fruitless discussions and consultations, as well as any further delay in assuming decisive actions for its protection?”

We perhaps all fear, as climate activist Greta Thunberg has suggested, that all talk—all “blah, blah, blah”—and no action may be the outcome of COP26. We perhaps therefore must all pray that politicians will at last agree when the Ecumenical Patriarch says, “It is inconceivable that we adopt economic decisions without taking into account their ecological consequences”.

If we agree with him—as Pope Francis clearly does from the teaching in his encyclical Laudato Si’—that care for creation is an act of praise of God, while “destruction of creation is an offence against the creator”, then perhaps we can even yet influence the COP26 negotiators.