Love for The Earth,

Love for Humanity

The bright light of the rising sun represents the luminosity, the beauty inherent in each human being and our capacity to transform evil into good and to establish authentic human relationships. The closeness of the celebration of Christmas envisions the coming of the Light and Peace for the world, the One that fulfils the greatest aspirations of any person and leads us all to God.

It is older, more radical, intimate, and more original to us than our own evil.

SPARKS OF A LIGHT FOR A WOUNDED BEAUTIFUL WORLD FALLING IN LOVE

WITH REALITY

The first to fall in love with reality, with trust and defenceless love, is God the Father. From his incurable enthusiasm for life, a project of love takes shape, declined with the alphabet of beauty. Sharing the same enthusiasm we, children of such a Father, can see the world with His eyes and fall in love with humanity, with nature, with everything that exists, as Jesus His Son did. We not only dream of the birth of “a new earth and a new heaven”, we also share it and make it happen

BY ERMES RONCHI OSM

CHRISTOS YANNARAS, a Greco-Orthodox theologian, wrote these words about falling in love: “If you fell in love once, you now know how to distinguish between real living and survival. You know that survival means life without meaning and sensitivity, a crawling death: you eat bread and can’t stand up; you drink water and don’t quench your thirst; you touch things and don’t feel them by touch; you smell the flower and its scent doesn’t reach your soul. But, if the beloved is beside you, everything suddenly rises again and life floods you with such strength that you feel the clay pot of your existence is unable to sustain it. That fullness of life is Love. Such love is not the privilege of the virtuous or the wise: it is offered to all with equal possibilities and it is the only foretaste of the Kingdom” (Yannaras, Christos. 2005.Variations on The Song of Songs. Holy Cross Orthodox Press, Massachusetts).

Reality is not only what you see, but all that can be put under this name, as long as it is not fictitious, but made up of people, eyes, stars, blades of grass, olive trees, birds, flowers, feelings, music, colours. How can you fall in love with reality? Two things are necessary: pure eyes and a spacious heart1 . For impure eyes can never see reality, and the hardened heart can never embrace it.

1 The author is referring to the Hebrew expression ‘rōhab lēb’, that is a listening heart, able to comprehend the fullness of the world phenomena, thus becoming a ‘spacious heart’. [editor’s note]

THE KEY OF BEAUTY

God, the Creator, sees and interprets reality with the key of beauty. Six times God cries to reality: “How beautiful!” The seventh time, seeing man and woman, He shouts: “What unattainable splendour!” The Creator of the universe is filled with wonder. He is not all-mighty God or all-knowing God, but all-loving God and all-embracing God.

We can all draw from this spring of divine wonder, at every dawn, which at times is so full of darkness. Made in God’s image and likeness, we too can embrace all reality, leading us to God himself, for all creatures are characters of a revelation.

When we talk about falling in love with reality, we think of the light and beauty that we see in it, and that must be enjoyed and transformed into sources of prayer and loving action. ‘The most beautiful thing is he whom you love’—the object of your love. “Beautiful is my beloved”, repeats The Song of Songs because the rule, the norm of beauty is love. Beauty and good come first, and are deeper than evil. This makes me fall in love with God’s plan, scattered in syllables on every face, in every womb, in every blade of grass, in every musical note. But… As the Irish poet Anne Brontë expressed: “There is always a ‘but’ in this imperfect world”.

but to human beings as well, who are discarded as waste.

DARK HOLES

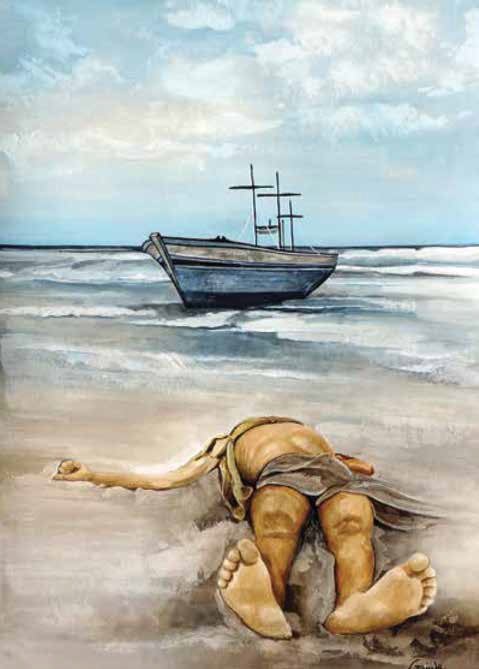

Reality is complex, made up also of dark holes: millions of jobless people, waves of refugees, burnt forests, spreading deserts, violence, famine, migrants drowned at sea, violated children. Dark holes are in the fabric of the world: Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the Rwandan genocide; the Apartheid regime; the all too many forgotten modern wars; the separating walls erected between one state and another, or between a social class and another, or between a rich city and its miserable suburbs. The dark holes are also the monstrous atrocities that occur at present: the raped woman, the suffering child and the old grandparent considered uneconomic, and hence, discarded.

The reality is not always understandable,

but is always embraceable and loveable.

Pope Francis’ ecological encyclical Laudato Si’ (LS) does not use the expression dark holes, but describes the situation in which our planet is moaning and succumbing to. Its first chapter draws a picture of the problems of the world, namely what is happening to “our common home”. After a period of “irrational confidence in progress and human abilities” [LS 19], we have to ask ourselves whether this is the right way to go. The “throwaway culture” [22] is shown as opposite to how nature works in sustainable cycles; this label does not refer only to material goods, but to human beings as well, discarded as waste, when they are no longer useful to support the needs of the rest.

Pope Francis’ encyclical offers the reader a depiction of climate change, The reality is not always understandable, but is always embraceable and loveable. Dark holes are in the fabric of today’s world. This label does not refer only to material goods, but to human beings as well, who are discarded as waste. 26 worldwide dec-jan 2021 worldwide dec-jan 2021 27 recognising that it “represents one of the principal challenges facing humanity in our day” [25], mainly affecting developing countries, the poor and more vulnerable populations, more dependent on natural ecosystems, and with less capacity to adapt. The text also presents other elements of the environmental crisis, such as the pressure on water resources or the loss of biodiversity.

Considering that the human and natural environment deteriorate together, Pope Francis turns the discussion to the poor, the excluded, those who suffer first and foremost from the effects of environmental degradation. “A true ecological approach always becomes a social approach” he says, and therefore, issues of justice have to be integrated into environmental debates, “so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” [49].

“A true ecological approach always becomes a social approach, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor”

The ecological crisis presents huge economic and ecological challenges, but Pope Francis sees it also as an opportunity for humankind to show its best while giving enthusiasm and encouragement to people. “Let us do it”, he says, “with the joy of knowing that it will be a beautiful collective effort that, beyond saving our common home, will make all of us become better human beings”.

The key to Pope Francis’ encyclical rests in his plea to “acknowledge the appeal, the beauty, the immensity and the urgency of the challenge we face” [15]. He sees an alluring beauty in our commitment to fight for the salvation of “the earth, our home, which is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth” [15].

TO LOVE IS TO GIVE

What can I do when confronted with these dark holes in history? How can I love them?

Scripture suggests one verb, concrete, proactive, and accomplished by hands: give! In the four Gospels, ‘to love’ is translated with ‘to give’. Jesus says: “There is no greater love than to give one’s life for one’s friends” (Jn 15: 13); and also: “I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink” (Mt 25: 35). Listening also with a spacious heart we discover the surprising truth in the

following verse:

“Whoever gives even a cup of cold water to one of these little ones… will certainly not lose their reward” (Mk 9: 41). What reward? God does not reward with things. God cannot give anything less than Himself—He is the reward. A glass of water— something close to nothing, which even the poorest person can offer; but there is a genial wing-beat, characteristic of Jesus: water must be fresh, good for the great heat; it must be the best water you have, with the echo of your heart inside it. Faced with this reality, disfigured by dark holes, we must fall in love with the cry of the poor and the cry of Mother Earth´.

“Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground” (Genesis 4: 10). Abel’s blood cries out to God. If we listen well, we will feel the pain for the cosmos, where crowds are killed, chased, driven into the pit, left alone, sick, frightened. Are they far away? No, if the heart is everywhere. How can I love them? I can give my sincere readiness to listen to their cry and let it enter my spacious heart. Then, a little big change happens: in an instant, I am made aware that I am not one who does something for them, but ‘I am they’, ‘I am theirs’. I am these people, threatened, frightened, hunted. I am here in their stead. I am Abel and Cain. I am the nameless man or woman who, at this moment, cries out in the forests of Africa, or in the war of Azerbaijan; is thrown back into the Mediterranean Sea from the satiated coast of the opulent West, or is blown up in Kabul. I am that man. That woman is my mother.

COMBATIVE TENDERNESS

Then, it is not a matter of giving alms, topdown, with the attitude of the conceited superiority of a rich man who deigns to part with an ounce of his smug selfishness to help someone who is sick and suffering, but of beginning to say: “I, in place of all the wretched of the earth” cry out in protest: “No! You don’t throw him overboard. Because that child is my son”; and in doing this with combative tenderness— a wonderful oxymoron created by Pope Francis (The Joy of the Gospel 85).

Honestly, what does this tenderness solve? What solution does it bring in the terrorism of Isis or Al-Qaida, in the stonehard hearts of politicians, in the havoc of hurricanes, in the ravenous exploitation of natural resources, in the mad pollution of the atmosphere, in the

desperation of migrants?

Tenderness can be tough. It never gives up. It always resists, and makes the world start again and again. Tenderness is intelligence and alertness. It is the U-turn of the vessel at the first signs of the approaching hurricane—for, if the ark of our history continues its journey in its present direction and with ever-increasing speed, it will

crash on the rocks.

Tenderness cries out: “Love each other… or you will destroy yourselves” (Gal 5: 14, 15). This is what the Gospel is all about, and it is the revolution. The response of Christians to persecution has never been a like-minded retaliation, but disorienting gestures, like turning the other cheek, offering a glass of fresh water, breaking their bread to the hungry, clothing the naked, and opening the doors of their houses to the unsheltered poor. Tenderness is the relentless patching up of the continually torn fabric of the world.

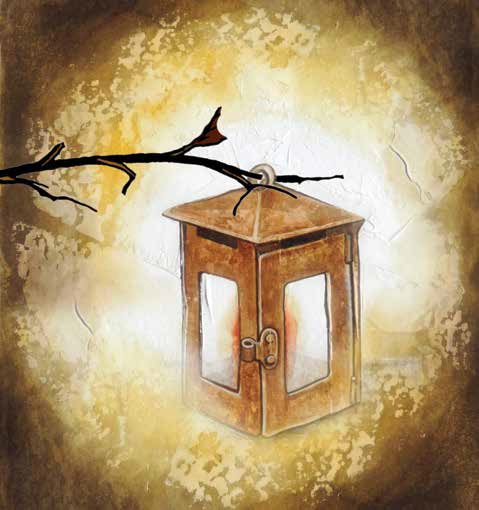

LUMINOUS HOLES

In opposition to the dark holes, we too offer the luminous holes, the possibility to escape from the present mortifying and moribund system of ours, and the chance to imagine putting the first bricks of an alternative scenario in place. If the dark hole is the space at the end of everything, the luminous hole is at the beginning of everything—a space of freedom on a human scale. It could be the bottom of the folder where the child hides its figurines, or the wall of the cell where the deportee writes messages of love and resistance, or a hermitage where a new road to God is traced, or a person who has stolen himself from the system of uniformity, a poet, a writer, an artist, a film director, a pianist, whoever they are, free and creative for themselves and for those

who approach them.

Our task is to find our luminous holes, our spaces of resistance, which very often are small (a corner of the garden, a book, a line of a poem, a church, a small Christian community, a friend), but all able to speak to us with ancient and new words, pregnant with light and truth. The strength of this luminous place is that of a little crack that works slowly and, in the end, makes the building collapse, without letting anyone die in it; a crack almost invisible, so small, but powerful enough to surprise you.

In this world of consumerism, you enter a supermarket, and, if you are free, you are no longer at the mercy of those who have prepared the shelves. You can decide what to buy, with a power that neither destroys the shelves nor shoots the supervisor, rather it sets out alternatives. You may buy a Cadbury chocolate or another bar produced with less human exploitation, and where the money that you pay goes to the co-operative of peasants and only a small part to distribution. With that little gesture, almost insignificant in most people’s eyes, you are pronouncing a strong alternative word and above all, thinking that there are alternatives. By choosing to buy that product, you act against the murderous economy that prevails in today’s world. You vote every time you open your wallet, not only during elections, and choose the type of world you

want to live in.

A luminous hole, no matter how small and pale,

teaches us that the world is still capable of amazing us

A luminous hole, then, is the idea that the world is also made of spaces for diversity, where not everything is standardized and the unexpected is possible. It implies not accepting the idea that everything is just the same, nothing will ever change. It means refusing to believe that it is no use trying: all are accomplices, aligned, cheaters, scared; this is falling in love with reality; having passion for the possible— the possible smile, the possible peace, a possible different world—is to believe in goodness. We must have pure eyes to spot it and spacious hearts to embrace it, to multiply it in myriads of luminous holes where the unexpected will open up for another economy, another community or way of praying, another humanism, other smiles.

in a mild, silent, subdued and free fashion.

THE WITCH OF ENDOR

We find luminous holes in Sacred History. The Spirit acts against the giant Goliath with a shepherd’s slingshot; contravenes Pharaoh’s decree, teaming up with two midwives, Shiphrah and Puah; puts his words in the mouth of a prophet that does not know how to speak, since he is too young. How beautiful our God, who works wonders with little things!

After the death of Samuel (1 Kings 28: 3–25), King Saul has banned from the land of Israel all mediums and those who consult the spirits of the dead. Soon after, he sees his kingdom falling apart. The Philistine army attacks his reign and he becomes frantic with fear. So, he goes to an old witch, able to consult the spirits of the dead. He meets her in a cave in Endor and asks her to summon the spirit of the prophet Samuel, who made him king so that he may ask for his advice. At first, the old witch is suspicious and thinks that the king has set a trap to unmask her and put her to death. The king swears: “As surely as the Lord lives, you will not be punished for this”. Evoked by the woman, the prophet appears and, with extreme harshness, announces to Saul his end and that of all his children. King Saul falls, full length on the ground, paralysed with fright because of Samuel’s words. He is also faint with hunger, for he has eaten nothing all day and all night. The old witch, knowing she is risking her life because her trade is forbidden, leans over the king and takes care of him. She takes her fattened calf and butchers it at once for him. She takes also some flour, kneads it, bakes bread without yeast, and breaks it for Saul. This old woman overcomes her bad trade, is transformed, and her loving hands and comforting words raise Saul up. She shows us that we are all potentially capable of doing better things and saying better words than those life makes us say every day.

It is a gloomy scene, taking place in a dark cave, but there is a ray of light— ‘an ounce of light’—that illuminates the cave, and we are witnesses of an intense moment of pity, created by an excommunicated witch, which beautifies the entire scene. What is it that makes her capable of light and piety, if not the Spirit of God and the deep humanness that is primordial in her and in us all (‘the beauty that is more original than original sin’) and is able to illuminate any anathematised woman or man and make them believe in goodness?

INFINITE PASSION

Infinite humanity of the Bible! It was ‘the last supper’ of King Saul. The words of the woman were the last living words the great king heard—words that life (Samuel and God) had denied him. The Bible is infinite also because of the gestures it narrates of ordinary men and women, often considered sinners and, therefore, discarded. These gestures allow the biblical word, at times, to be more human than the words spoken by the prophets, and the very words of God spoken by

his official emissaries.

Dark holes are there, but there are also unexpected luminous holes. When you approach a person with pure eyes, you discover cracks that open up to infinity. The person you thought was lost is, instead, a wayfarer. There is sickness and death around us, wars, fake news, lies, violence, and rejections, a haemorrhage of humanity in the world, which is groaning everywhere, with open veins. However, there are also witches who become merciful mothers. If I look at anything that exists with pure eyes and a spacious heart, I then become passionate about what exists in all its forms.

Passion means both being fond and suffering. Faith opens the heart to suffering and makes one passionate for everything that lives. An infinite passion is a never-finished relationship that leads you to love heaven and earth with the same intensity. You cannot sing hymns in a church and, outside, be indifferent to the rubble and the beauty of history.

I can fall in love with reality because I feel that it is not only

a problem to solve, but also a joyous mystery, a mystery

I can enjoy to the point of falling in love with it.

TIRELESS SEDUCTION

The surrounding reality often comes to us as suffering, a scratch, a claw mark on the heart, but it also reaches us with a tireless seduction. Take the mouth of a new-born baby. It is only a few minutes old, and yet it already knows the fundamental philosophy of life: reality is not made of thought, but of body and soul. Even before reaching the mother’s breast, the mouth sucks the emptiness, confident that the breast will appear, because it exists. The baby’s reality is made of emptiness and fullness, of desire and contentment (St Augustine would add: “… and of a restless heart and God”). Life comes as a gift and as a grace, from a reality that

is external.

There is a second lesson we learn from the baby’s lips. The mother’s breast is not only the hill of milk and a means of subsistence. It is an object of enjoyment. By sucking the breast, the child enjoys the blessing. The same holds true for reality, which is not only what keeps us alive and without which we could not live, but it is also a principle of delight.

We find this aspect of reality—as a joyous mystery—looking at some attitudes of Jesus in the Gospel, what we could call ‘the pedagogy

of Jesus’.

Let us take the parable of the sower. The man may seem unwise to us as he threw the seed on brambles, thorns and stones but in doing so, he showed one truth: God embraces the imperfections of the field. Nothing is discriminated against and excluded. No one is just a trodden path, a rocky place, or thorns.

We are all like the field of the parable, wounded, dull, hard, stony, thorny, unfinished. Yet, the loving hand of God continues his creative work tirelessly, certain that this imperfect humanity of mine is fit to give life to the seed of His word. Imitating this divine generosity, the sower widens the gesture of his arm and breathes better, because he believes, not in a nicer, almost perfect reality, but in one more true and authentic.

It invites us to fall in love with a field where good wheat grows with weeds, and with a bush though it is sprinkled with brambles; not a cornfield where the rows of the stalks are perfectly aligned and the ears have the same number of grains, where pesticides have killed every type of grass. Instead, we fall in love with the imperfect field, the defective tree, the flawed vineyard where vine diseases are shown on the leaves. In perfect vineyards, you will never find powdery mildew: just empty jars of poison, labelled with a dead man’s skull, not a single luminous hole enfleshed by a goldfinch with its note of freedom and joy in the air, not a squirrel, not a flower, not a broken branch, not a grape embellished with the visit of a butterfly.

The Gospel is full of seeds, shoots and buds swollen with life, whose territories are unfinished, unstable and in-the-making. We, too, are not in the world to be immaculate, but to be on the move; not to be perfect, but to be fruitful—at least of a gram of light. Called to be children of light, we must not fear night too much, but love it a little, because the most important things happen at night. Do we not celebrate the night before Christmas and the night that turns into the Easter dawn? Does not the night transform men and women into lovers? At night—in every night of the world—there is a role for us.

the initial, fresh, rising moment of the Gospel”.

(“He taught them in parables”, watercolour by Maria Cavazzini Fortini)

SUBVERTING LAMP-BEARERS

Lamp-bearers are always there; little prophets who explore new trails. It is fascinating to see the world with the gaze of Jesus, not from the top of a castle or from the pinnacle of the temple, but from our house garden; read the Gospel from below, or rather, from the ground, to annul, thanks to a mustard seed, the distance between God and the earth, and to realise that the divine transpires from the depths of every being.

It is fascinating to see the world with the gaze of Jesus;

read the Gospel from below, and to realise that the divine transpires from the depths of every being

The Gospel of Jesus—the Good News of Jesus who loves the earth—subverts all norms: it encloses the great in the small, the high in the low, the contents of faith in the secular language, the sky inside the earth; it leads us to the school of the vine, of the blade of grass, of the fig tree, because the laws of the spirit and nature coincide. The norms that govern the coming of the Kingdom of God and those that nourish the life of creatures are the same; and you perceive that it is proper of nature, of plants, of God and of man to offer fruits, shelter, coolness, rest.

From Jesus’ parable of the sower, read from a new perspective, emerges a beautiful vision of the world. What is this history of ours if not a sowing, a germinating, a sprouting, a growing, a grain filling,

a ripening, a harvesting?

Everything, with its mysterious rhythm, is an ever-growing trust and a joyful surrender to life on the way towards fruitfulness, the unknown divine power of the smallest seed. If, at every spring time, one is able to marvel at the ‘wisdom of the earth’, then it will be clear that there are good forces at work in the world. Someone cares to keep them alive and multiply them, despite stones and thorns.

SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL

Jesus is in love with smallness as it runs through the whole Bible. It represents its deepest soul: the master seed, Abel, the first human seed hidden in the earth, sterile mothers with tears of humiliation, Joseph sold by his brothers, Amos, a herdsman and a dresser of sycamore trees, Jeremiah, young, shy and sentimental and moreover stammering, Mary, the little servant of the Lord, Bethlehem, “the smallest among the clans of Judah” (Micah 5: 2), Golgotha, little rock of the crucified God, YHWH a “thin voice of silence” (1 Kings 19: 12).

Taking the economy of smallness seriously leads us to wade the world in another way, to look differently at our wounds, and to seek out the kings of tomorrow among the discarded and the poor of today. It will enable us to take the young people and children very seriously, to find merits where the economy of greatness—the economy of scale—sees only demerits.

When Samuel goes looking for a king in the house of Jesse, all his sons are there. Only David is absent, the youngest, grazing the flock. The prophet sends for him. God wants him. Work is not the obstacle to discover our vocations. The most important theophanies and the greatest vocations simply happen while we are inside reality—grazing the flock, or fishing in the lake. To understand our place in the world, we can do nothing better than continue to be inside reality through our little work. God’s love encloses the great in the small, the universe in the atom, the tree in the seed, man in the embryo, the butterfly in the caterpillar, and eternity in the moment.

Faced with the darkness of history and of many hardened hearts, the combative tenderness cries out “No! You cannot do this; that forest, that river and that lake belong to all humanity; that man is my brother and that woman is my sister and mother.

OPPOSING DEATH HOLES

During the Special Laudato Si’ Jubilee Year, we are invited to open our eyes and dilate our hearts, to see, feel, and understand reality, by increasing the capacity for attention, curiosity, openness and creativity. Our present problem is that of having shrunken hearts, scaled down to the measure of one’s self, of one’s hunger, of one’s needs. Pope Francis urges us to reverse this course of death.

Faced with the darkness of history and of many hardened hearts, the combative tenderness cries out “No! You cannot do this; it is not lawful for you to do that; that is against the common good; that forest, that river and that lake belong to all humanity; that man is my brother and that woman is my sister and mother”.

that proliferate inside the dark holes of history, ready to risk, with inventiveness and freedom.

So, with infinite tenderness and tireless combativeness we can continue our battle against all the dark holes of history, in favour of all possible luminous holes, many already present but kept hidden or impeded from shining. This battle against evil will make us fall in love with good more and more. And, as lovers of good, we will free the best and most constructive energies, embrace the imperfection of the world, and live a deep communion with the whole. These are the necessary conditions to give existence to a positive new world narrative.

Could the Pandemic Create a Less Exclusive Economy?

THE COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the global crises that were already there, the recognition of a dysfunctional economy and the driving force behind highly unequal societies—which favour new paths, fears and hopes, but the future remains unknown.