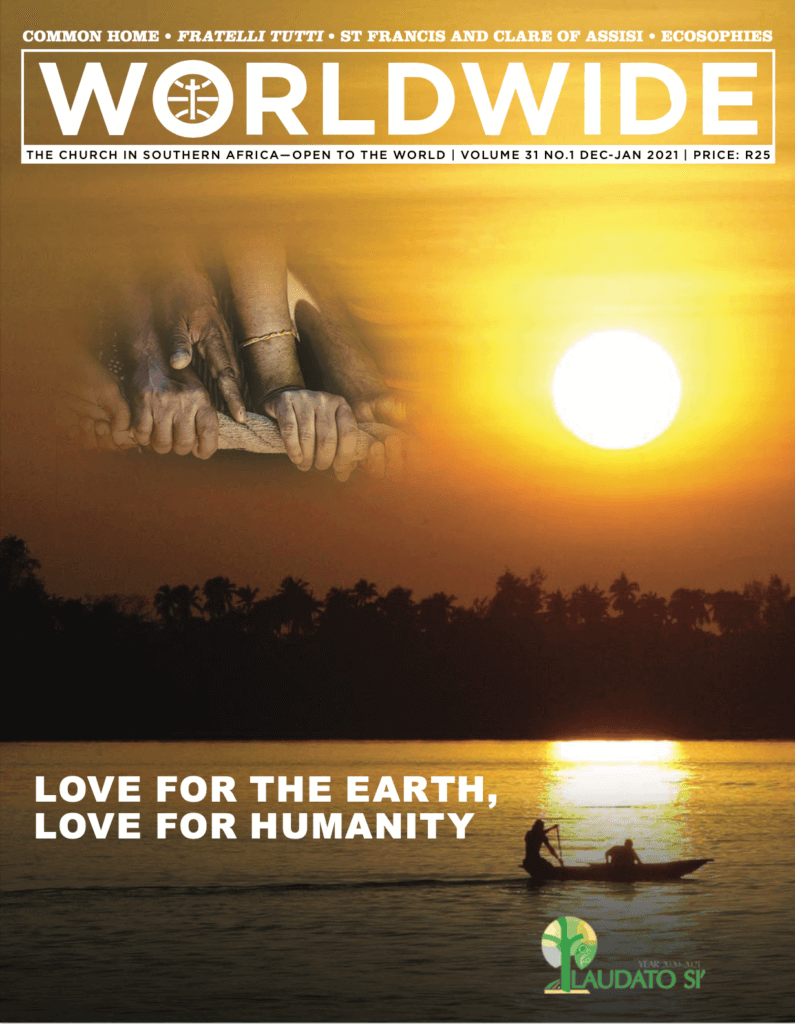

Love for The Earth,

Love for Humanity

The bright light of the rising sun represents the luminosity, the beauty inherent in each human being and our capacity to transform evil into good and to establish authentic human relationships. The closeness of the celebration of Christmas envisions the coming of the Light and Peace for the world, the One that fulfils the greatest aspirations of any person and leads us all to God.

A WALL FOR A GREENER AFRICA

The first idea of creating a green barrier against the growing desertification of Africa was conceived in 2005 during a regional Conference of African Heads of States in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Two institutions, the African Union (AU) and the Pan-African Agency for the Great Green Wall (PAGGW) for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative, are currently leading this programme, aimed at reforestation

BY MARTA GATTI | ITALIAN RESEARCHER AND JOURNALIST

THE GREEN great barrier would consist of a 15 km wide strip, from Senegal to Djibouti, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, for a total length of about 8 000 km, across 13 countries in the Sahelian area. It aims to regenerate 100 million ha of degraded land by 2030, capture 250 million tons of carbon from the atmosphere and create 10 million jobs in rural areas, directly contributing to the UN’s sustainable development goals. The Wall has promised to be a compelling solution to the many urgent threats—notably climate change, drought, famine, conflict and migration— facing not only the African Continent, but the global community as a whole.

The way to achieve that ambitious mission has been planting trees to stop the advance of the desert, reverse land degradation and to help curb the impoverishment of the population. It aims also at boosting food security, and through an eco-sustainable economy, support local communities so as to adapt themselves to climate change.

Various actors are also involved in the project, the UN Organization for Food and Agriculture (FAO), the World Bank with The Sahel and West Africa Program (SAWAP), the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the European Union as well as other African

regional organizations.

The initiative has now been expanded to a vaster territory, surrounding the Sahara Desert: north of the Sahelian belt, and in the south, up to Benin, Togo and Ghana, countries initially excluded. It involves, at different levels, a total of 22 countries and 232 million people who live in the area surrounding the Sahara and would benefit from the project.

RESULTS

It is difficult to understand what the achieved results actually are. According to www.greatgreenwall.org, a website managed by the UNCCD, a decade in, and roughly 15% of the total final objectives would have been reached. The site states that the initiative is already bringing life back to Africa’s degraded landscapes at an unprecedented scale, providing food security, jobs and a reason to stay for the millions who live along its path. Once complete, the Great Green Wall will be the largest living structure on the planet, three times the size of the Great Barrier Reef. There is, however, no mention of the number of jobs created. (https://www. greatgreenwall.org/).

The figures vary a lot if we use the PAGGW as the official source: three million hectares regenerated in 11 countries and 11 000 permanent jobs created. The records are still different if we take into account the numerous programmes created in support of GGW.

A COMMON STRATEGY AND THREE CRITERIA

In 2012, the Harmonized Regional Strategy, still in force today, was adopted by the leading institutions of the project, aiming to standardize and provide guidelines to the acceding countries. According to this document, the project intentions to conserve, develop and manage natural resources and ecosystems, strengthen the infrastructure and potential of rural areas, diversify economic activities and improve the living conditions of the communities. These are, therefore, multi-sectorial actions which must be integrated.

In the opinion of the scientific and technical director of the PAGGW, Abakar Zougoulou, there is still a problem of a misunderstanding among the many institutions that follow the inspiration of the project, but whose actions are not part of it. “In order to be considered part of this initiative, three criteria indicated in the Harmonized Regional Strategy must be respected. The first is about the geographical space, the circum-Sahara, from the Maghreb to sub-Saharan Africa. The second refers to the portion of territory in each state: i.e. areas with the lowest rainfall, from 100 to 400 mm. This has been identified by the African scientific community as a priority area for intervention.

Up to now, 28 million ha of land have been regenerated and 12 million trees have been planted in five of the twenty-two countries that have joined the project

The third criterion applies to the species of plants used. “About 200 species have been identified, based on their adaptability. Not having enough funds available to cover the entire part of the countries, priority areas had to be chosen. All institutions that want to be part of the project must take this into account, but often they have not done so”,

says Zougoulou.

According to him, only recently have the partners understood the need to act first in the low rainfall areas and then expand their action outside. Considering the three criteria mentioned above, many World Bank projects would not fall under the GGW initiative because their actions have touched areas of the countries outside the indicated rainfall zone.

THE KEY IS AGROFORESTRY PASTORALISTS

The ecological rehabilitation of this area must take into account several factors, not the least, the access to land. Farmers and shepherds are the main protagonists of the Green Wall. Hence, the project must involve the community farms in the natural reforestation process.

In Ethiopia, for instance, to combat depopulation, the World Bank has envisioned making some rural areas more attractive so as to retain their inhabitants. In Niger, agroforestry systems, combining tall trees and annual crop production, have been adopted. FAO has focused its projects on introducing various agricultural techniques and technologies as well as developing local skills and competencies. Native plants that are useful to communities, as a source of timber, food, fodder and as a sale product, have been incorporated. In particular, initiatives with gum arabic, forage, seeds and oils of local species have been developed. FAO ventures have focused on agroforestry systems that guarantee food, income and market. “The main beneficiaries are women involved in the processing and sale of plant products”, points out Nora Berrahmouni, regional head of FAO for Action Against Desertification projects in Africa.

FOR THE PEOPLE AND BY THE PEOPLE

The motto of the PAGGW has been ‘for the people and by the people’, a multisectorial, inclusive and ecologically based approach that involves people in an active, conscious and voluntary way. These are community farms originated from a village or a group of villages. Up to now, there are six active projects that have to be replicated. In farms of about 3 000 ha, horticulture, beekeeping and small animal breeding are developed. The venues are identified on the basis of the three mentioned criteria: geographical, social and cultural homogeneity of the populations, the amount of rainfall in the area and the adaptability of the species to be included. The reforestation programmes involve areas between one village and another and include the cultivation of plants considered strategic, such as gum arabic, moringa and spirulina (commonly called spirulina algae, a cyan bacterium rich in proteins). Water management takes place through the conservation of rainwater and the construction of large wells.

The Green Wall area includes community gardens, pasture areas, spaces for fruit and income trees, beekeeping initiatives, among others, multisectoral activities that guarantee an additional income to the local populations

In some cases, specific technologies have also been introduced, such as the Vallerani System, a mechanical tool made up of a plough and a tractor that allows the tilling of arid and semi-arid soils in order to rehabilitate degraded soils. This technology also optimises the conservation and the rational use of rainwater. Technologies are not always welcomed at the level of individual countries; sometimes fear of losing jobs replaced by mechanical tools, emerges.

In other cases, GGW has appropriated local techniques used by farmers and shepherds. This is the case in Burkina Faso where the zaï system has been adopted and even exported. It consists of small holes made in the ground, enriched with manure, in which water is collected, making the soil more fertile. This is a traditional technique made famous by the Burkinabe farmer, Yacouba Sawadogo. Among the methodologies adopted by the projects, assisted natural reforestation is also used.

It provides for the protection of indigenous tree species which are normally cut or burnt to fertilize the land used for

agricultural production.

SOCIAL REHABILITATION

Among the difficulties encountered, the main actors involved in the GGW mention the insecurity in some areas of Sahel, the conflicts in spaces where water resources are very scarce and the abandonment of the countryside. To avoid the emergence of conflicts within the communities affected by the projects, the PAGGW has adopted the above-mentioned criteria of homogeneity; a system that may also risk exclusion

instead of inclusion.

The right of access to land was one of the issues raised, particularly taking into account the logic of transhumance and the involvement of nomadic users of the land. “Often the aim is to close the spaces of use, without attempting to reconcile the different activities. In cases where the land aspect has not been taken into account, the project has failed”, stresses Mélanie Requier-Desjardins, a researcher at the Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Montpellier. She took part in the drafting of the document, The African Great Green Wall Project: what advice can scientists give? edited by the French Scientific Committee on Desertification. According to the researcher, moreover, it must be clear that the ecological rehabilitation of a territory must also be matched by a social rehabilitation: “If free access land is transformed into areas forbidden for some, inequalities are generated. For example, when the rehabilitated areas are assigned to farmers who have many animals, we lose the small shepherds”. The initial project focused mainly on agricultural communities according to Mélanie.

Abakar Zougoulou has a simple solution for involving nomadic populations too: “Shepherds can use the undergrowth pasture and collect forest products. They can produce straw and fodder to store and use them in the dry season”. FAO has focused on plants that are useful to shepherds, integrating the interests of each productive activity, to avoid conflicts. In some cases, the solution found, mentioned by the PAGGW, was that of fences. The debate is still open.

In Senegal, the only country to have started reforestation on the whole 15 km wide strip of land, a change of strategy has been made. Youssef Brahimi, a former member of the UNCCD Global Mechanism, an institution created to assist countries to mobilize financial resources to address desertification, land degradation and drought, states: “They started with reforestation, but afterwards they realized that the itinerary included villages and communities. Therefore, they also included vegetable gardens, with a particular contribution by women”.

In the Harmonized Regional Strategy, explicit reference is made to ensuring fair access to land resources for all the populations living in the arid areas. Brahimi participated in the drafting of the document: “The securing of land has been promoted not only on an individual level, but as a common good, through community management. We felt pressure from institutions to develop national land legislation that would allow individuals to have a right to land—but we know that where there is an individual property right, it serves to put the land up for sale. That is why most projects have set up community management committees. Action Against Desertification projects, for example, are carried out on community land, in agreement with municipalities and mayors. The land is identified by involving the population and the local administration. “The existence of a management committee is important because it allows to locate the land and to record its use in an official way”, points out Nora Berrhamouni, FAO regional co-ordinator.

it has been adopted as a global symbol for all actions oriented to combat climate change

and soil degradation through the valorization of trees and green natural areas.

PRIVATE PARTNERS

In regard to the entry of private capital, not all the partners of the GGW share the same attitude. According to the PAGGW, private capital is not needed because “they would take most of the hectares”. The FAO is not of the same opinion, as it has produced a document aimed precisely at private individuals who want to invest in land redevelopment activities. The call for private capital has also been launched by the African Union and the World Bank.

In any case, in most countries, land belongs to the state and it is the state that decides its use. Abakar Zougoulou explains well what this means: “If oil is found in an area where reforestation has been carried out, it is unlikely that trees will remain”.

Could the Pandemic Create a Less Exclusive Economy?

THE COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the global crises that were already there, the recognition of a dysfunctional economy and the driving force behind highly unequal societies—which favour new paths, fears and hopes, but the future remains unknown.