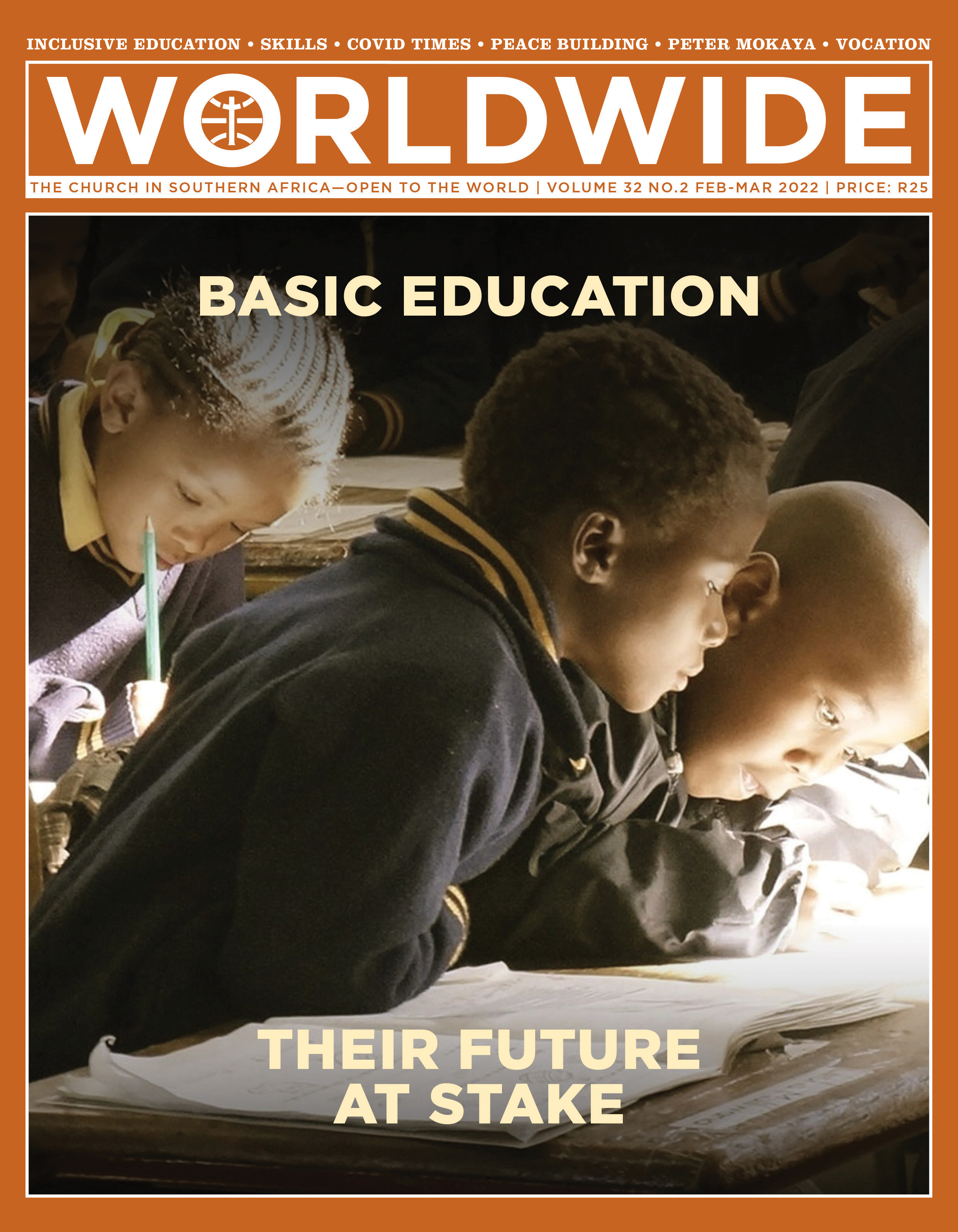

Basic Education Their Future At Stake

The front cover picture was certainly not taken during Covid times. We do not know its exact location, but it could be from any particular school in rural South Africa. What indeed the image of these children reflects is their eagerness for learning and doing it together. Their minds are surely full of dreams; their desires for a bright future cannot be frustrated. The task of offering them an inclusive and integral quality education can look gigantic, but each one’s contribution can make the miracle happen.

FRONTIERS • VOCATION

“My Dream Is To Share The Word Of God With Those Who Have Not Heard It”

Simon Yomkuey is a Comboni Missionary from South Sudan. He attends his second year at St Joseph Theological Institute at Cedara in Pietermaritzburg, Kwa-Zulu Natal. While spending some days in Pretoria, he shares with us his vocation journey

BY

Rafael Armada, MCCJ

Interview with Simon Yomkuey

Simon, what can you tell us about your background?

I was born in 1988 in Mayom County, Unity State in South Sudan. My parents were pastoralists, not rich but like other South Sudanese. We are four boys and two girls, all Catholics. My father died when I was about 8 to 9 years old and my mother died in 2006 when I was at the University.

I moved to Khartoum with my brother in 1993. We had a house in the area of Ordurman. I attended the Comboni primary school in Bahry. From childhood I was very active in the parish run by the Comboni Missionaries. I was an altar server, choir conductor, a member of the parish council and chairperson of the Legion of Mary, a strong movement in the Catholic Church of Sudan.

How did your interest in becoming a Comboni Missionary arise?

I began to know the missionaries in the parish, though at first, I had no idea of becoming one of them. We had a weekly session about callings where they would explain to us, boys and girls, the various vocations, and how to become one of them.

During secondary school, I started showing more interest in the Comboni Missionaries. When I finished school, Fr Norverto Stonfer and Fr Adam Dawd Abushok, a diocesan with whom I used to share my queries, advised me to continue studying: “You can always tell us if you are still interested, after the University. We know you very well; it will be very easy for us to recommend you.” So, I proceeded to the School of Management, Department of accounting and finance. In 2011, the referendum of independence of South Sudan was celebrated, and the University was transferred to its original place, Juba. I moved there where I graduated in 2013.

How was your journey into the formation stages?

I had spent my whole life in Sudan, so I did not know where the Comboni’s were in South Sudan. The opportunity to find them happened on a Sunday. A priest came to our Holy Rosary chapel. After the Mass, he said: “my name is Guido Oliana and I am a Comboni Missionary.” I told him that I was interested in meeting the Comboni’s and after some days, Fr Louis Okot—then vocation director—phoned me. I met him and he asked me for a recommendation letter. Fr Adom Daud, a diocesan and then my parish priest, wrote it and sent it to him. Fr Louis invited me to a one-year programme called ‘come and see,’ during which we used to meet many aspirants, boys and girls, in the provincial house, every last Saturday of the month. They would explain to us about vocations, providing booklets of the life of Comboni, and other materials. Sometimes we would go to Kajokeji, where the pre-postulancy was, and stay for a week. Fr Louis would say: “You pay your transport to reach there, and returning, I will see if I can take you back to Juba”. After a year, in 2014, I was admitted to the six-month pre-postulancy, followed by an experience in a parish. Then, I moved to Nairobi for the postulancy, where I study a three-year philosophical course, followed by a two-year novitiate in Namugongo, Uganda. I professed my first religious vows, on 23 May 2020.

After the novitiate, I was assigned to the scholasticate of Pietermaritzburg, in South Africa. I could not visit my family—I had not seen them since 2018—because Uganda was under Covid lockdown. While waiting, I took the opportunity to stay in the Comboni community who works with the South Sudanese displaced in Uganda. When the borders eventually opened, I returned to Juba and, before South Africa could close them again, I entered the country.

Why a Comboni?

Vocation is a mystery. I really admire some priests whom I have encountered. When I was in the University, I had a strange feeling, as if I was forgetting something, or something was missing in me, though I couldn’t name it. I used to prepare my school books, clothes and shoes for the following day, yet my mind kept telling me that something was missing. When the idea of joining the Comboni Missionaries came, suddenly, that strange feeling disappeared.

Their simplicity, kindness, sense of belonging, way of receiving, listening and trusting people inspired me

What inspired me, from the few Comboni’s whom I knew in my parish, was their simplicity, kindness, sense of belonging, their way of receiving, listening and trusting people. No one saw himself greater than others; there was an element of equality. I also learnt from their sacrifices. All this motivated me to join them.

I also got inspiration from Fr Lual, a South Sudanese Franciscan priest, who was working in Egypt. When he came to Sudan, he used to celebrate Holy Mass in my parish. His homilies, and how he could talk about unity touched me.

Has your perception of the Comboni’s changed from your first encounter up to now?

Not really. Though I have found different characters, I also discovered that goodness is something that a person cultivates and nurtures. In the end, what one nurtures is what matters.

What have you gained in these years?

I have learnt how to stay with people of different backgrounds, cultures and ideas. I have gained education: philosophical and theological studies, catechesis and knowledge about St Daniel Comboni and how he started this Congregation.

Comboni sacrificed a lot and put his feet in the shoes of others.

What attracts you most in Comboni?

Comboni was passionate about taking the Word of God to those who had not heard of it; he sacrificed a lot and put his feet in the shoes of others. His homily at Khartoum, after coming back from Italy, when he said: ‘I have come back among you today. I left, but my heart was still with you. Young and old, poor and rich, healthy and sick, I will be your servant,’ inspired me a lot. I try to imagine the area where he was staying, both in South and North Sudan, difficult places, a foreigner coming from very far—it was not easy.

The trips he made southwards through the Nile, against the water current, were really hard. At least, travelling from the South, the water flows towards the North and is better.

How is your experience of a multi-cultural community?

In our scholasticate, we come from ten nationalities and three continents. One has to balance one’s culture with others’ and use a universal language. If one is not sensitive, it can make life very difficult. For instance, in South Sudan we eat kesira, (paper food). It will be awkward if I intend to eat kesira every day because others also have their favourite foods.

I find this experience unique and enriching. It allows one to enter into oneself. If the person staying with you sees you as a brother, he finds it easy to come and help in your weakness or correct you. The challenge comes when you don’t see others as brothers, you lack trust and decide not to share your problems with them.

How were the periods prior, during and after independence in your country?

The South Sudanese fought against the Northerners for more than twenty-one years, demanding their freedom. Independence came, though people are still facing some challenges.

Prior to independence, when we were one Sudan, the South Sudanese saw themselves as brothers and sisters. Their unity was incredible. Whenever a Southerner was involved in problems with the Arabs, anyone would come to their help, being either a Southerner or a Northerner, their colour was enough in assisting to solve the problem. Then, when the police came, they would not differentiate who was or was not involved in the incident; if you were a Southerner, you would be taken to jail.

When Sudan was one country, in public transport, if a black person was not able to pay their fare, another black would pay the money, even if they did not know each other. If one did not have a place to sleep, others would welcome them in their homes. In schools run by the South Sudanese, they could not chase those unable to pay the fees.

In those times, the same hospitality was happening in the South; the liberation fighters were getting sustenance from farmers and pastoralists. The soldiers could come to a village and ask the local chief for food. He would go to each family and ask for their contribution of a cow or a goat. Even if the fighters were arrogant, people would remain calm. They knew their mission and their goal were one with them. When the South Sudanese voted for independence, the result was impressive.

Before independence, the South Sudanese saw themselves as brothers and sisters. Their unity was incredible.

I never expected that, later, something would change people’s minds and plunge the country into the current situation. It was like saying: ‘let´s remove our common enemy so that we can start fighting among ourselves’, killing each other. Death comes easily for those who yesterday were together. How can people hate each other like this? It is unbelievable. Though we say we are free, there are no good infrastructures in the country, for instance, roads, hospitals, schools, and insecurity is everywhere. Is it the money from oil and gold which becomes our curse? I cannot understand it.

What have you discovered in your faith journey during these years?

I have discovered that with God, nothing is impossible; there is always a possibility. I have also understood better my relationship with Him, my existence; that all comes from Him. When I think of the problems and situations I came across, I saw that it was God who was leading me through all these obstacles. He was working with me silently. When there is a glimpse in my path, He shows me the way. I believe in His actions, even now, during this interview, He is beside me.

Credit: Simon Yomkuey.

How does your culture accept the idea of celibacy?

According to my culture, not marrying and having children is taboo. I can understand it, but not those where I come from. They believe that such a thing cannot happen. If one says ‘I want to become a priest or a nun’, people will conclude that this person is impotent and is hiding it by going to the seminary. In my tribe, the Nuer, no one had joined the Comboni’s before, I am the first one, though Comboni was always passing my area in his journeys to Southern Sudan. That issue with my tribe was a big struggle. Cultures differ from one another, but now we are all happy with my choice.

My brother’s son wanted to get married. My brother told him: “no, Simon should marry first, then you, who are our children, will follow him”. I had to talk to my brother so that he would allow his son to get married.

What is your impression of the September 2019 peace agreement?

It is better than nothing. What is still at stake are those in the camps for internally displaced persons and the refugees in Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Congo and Sudan. They could come back, but they have lost hope and decided to remain in those countries where their situation is unpredictable. They have nothing to eat and they are homeless. UN supports them, but there is no guarantee for the future.

We cannot wait for the people to come to us; we need to reach out and motivate them.

The security is not good, people are attacked and killed on the roads, along the highway, not necessarily by rebels, but by hungry people who, not getting their daily bread, become robbers—a very unfortunate situation. There is also trauma in the minds of the people.

What is your experience in South Africa?

I have been in South Africa for one year. I like the country, their development, infrastructures—roads, good hospitals, schools; the government is trying its best to deliver services. The teachers in the theologicum are also highly qualified. What I don’t understand is the security issue; when you go to malls, you find guns being displayed; that shocks me. For the rest, I really appreciate the South African people.

What is your dream as a Comboni Missionary?

My dream is to share the Word of God with those who have not heard it. It can be physically, or through mass media. Technology allows us to reach far beyond our surroundings. My aim is to reach those that are abandoned, disowned, like those living in slums. We need to solve their cause of abandonment and engage also with those who try to isolate them from society. People need to understand that we are all the same, though with different talents. The only difference is how we use them. Those who consider themselves higher than others must comprehend that what they are now was not of their own making, but God was behind their success.

Are we, as Church, trying to transform the causes of injustice?

Yes. Injustice is one of the key issues in the downfall of our dramatic world. When we explain to the people that there should be justice in whatever they are doing, even at home, we make the world review itself. The Church tries to make the people of the world slow down and see what is going on around them.

Simon, wearing number 15, playing soccer with his companions of the Postulancy, in Nairobi, 2018. Credit: Simon Yomkuey.

Is ecology and Laudato Si’ a concern in South Sudan?

No. Laudato Si’ is something very far from the people. Maybe less than five percent of the population can understand what it really means to take care of creation. The majority are not educated, so, the idea is far from their minds.

Do you see the effects of global climate change in South Sudan?

Yes. No one is concerned with the consequences of human activities on climate change, which eventually affect people in a mysterious way.

In which direction should our congregation grow or improve?

We are lacking local investment. We have been depending on aid from outside. We are here in South Africa, Malawi, Congo and other countries, but we don’t produce locally to support ourselves and our congregation. Schools are very important too; through teaching, Comboni’s vision can be actualized and help others, not only to evangelise and baptise people. We need to review the method used by our founder who had tailors, shoemakers, schools for orphans, doctors, builders, clinics, boats and seminars. Do we have them now as a means of “saving Africa by Africa”?

Why do you think that there are few vocations in South Africa?

Some congregations have no vocation promoters, but still young people join them. I am wondering why. Instead, I asked myself: what is wrong with congregations that have vocation promoters? We cannot wait for the people to come to us; we need to reach out and motivate them. Laws and rules that we do not practise ourselves, we cannot demand from them. Distribution of publications about Comboni is not enough. One might have no time to read them. We may even block young people by saying that we only need those who have finished school. Instead, helping someone to complete their secondary school and incorporating them in our structures of formation may inspire them to find their vocation. In this way one attracts young people.

| Dates To Remember |

|

February 1 – Blessed Benedict Daswa 2 – World Day of Prayer for Consecrated Life 4 – International Day of Human Fraternity 6 – International Day of Zero Tolerance of Female Genital Mutilation 8 – International Day of Prayer and Awareness against Human Trafficking 11 – International Day of Women and Girls in Science 11 – World Day of the Sick 13 – World Radio Day 20 – World Day of Social Justice 21 – International Mother Language Day March 1 – Zero Discrimination Day 2 – Ash Wednesday 3 – World Wildlife Day 8 – International Women’s Day 15 – St Daniel Comboni’s Birthday 20 – International Day of Happiness 21 – International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination 21 – SA Human Rights Day 22 – World Water Day 24 – World Tuberculosis Day 24 – International Day for the Right to the Truth concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims 25 – International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade |

Awesome content and organization on your website dude, very useful to me and everyone.

Dear website viewer

Thanks a lot for your comments of appreciation and sorry for answering so late. I was not following properly the communications. My apologies. God bless you