SYNOD ON SYNODALITY (2021–2023)

The cover illustration represents the exercise in which the Church is invited to engage in this process of synodality. Gathered by the Lord and guided by the Holy Spirit, through a journey of prayer, the people of God from all continents, representing diverse ages and kinds of lives, come together to listen to each other, including those marginalized, participating and reflecting on how to be transformed into an inclusive community sent to the mission in the world.

FRONTIERS • SUDAN

Credit: Comboni Missionary Sisters.

Indomitable Women of the Gospel

Celebrating the 150th anniversary of their foundation (1872–2022), the Comboni sisters wish to recall the heroic testimony of faith by some of their members who endured great suffering and persecution during the Mahdi’s revolution soon after the death of the founder St Daniel Comboni

BY Paola Moggi | Comboni Sister, Verona, italy

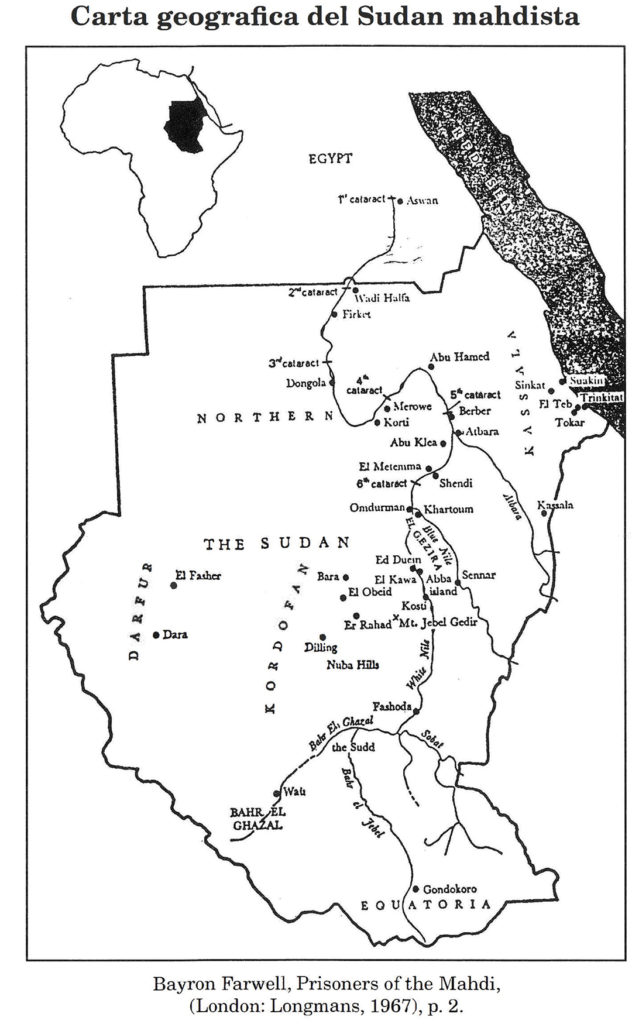

FROM 1881 TO 1898, the Egyptian Sudan was overwhelmed by an Islamist religious insurrection known as Mahdia named after its spiritual and political leader, Muhammad Ahmad, who called himself the Mahdi (which means well guided by God). His declared aim was to restore the purity of Islam, corrupted by prolonged contact with Europeans. However, the socio-political reasons for the uprising were others: to enact the widespread discontent with the Egyptian misrule and to restore slavery, an important economic resource in the region.

The Mahdi’s uprising

The Mahdi’s advance towards the central region of Kordofan took place while the staff of the Catholic missions—mourning for the sudden death of Daniel Comboni (10 October 1881)—paid little attention to it.

The Egyptian government, which was wagering on its twenty regular battalions, underestimated the insurrection. The Mahdi militias, supported by powerful slave traders and fed by numerous defections of government officials and soldiers, quickly conquered Kordofan.

In May 1882, the fighting reached the Nuba Mountains and Delen (or Dilling), the seat of a Catholic Mission. In August, the capital of Kordofan, El Obeid, was besieged and it surrendered due to starvation on 18 January 1883. Those who had not professed the Islamic faith had to embrace it under threat of death, so that missionaries became sought-after prey of the Mahdi to further fuel his mythical aura.

We answered that we were Christians and intended to die as Christians

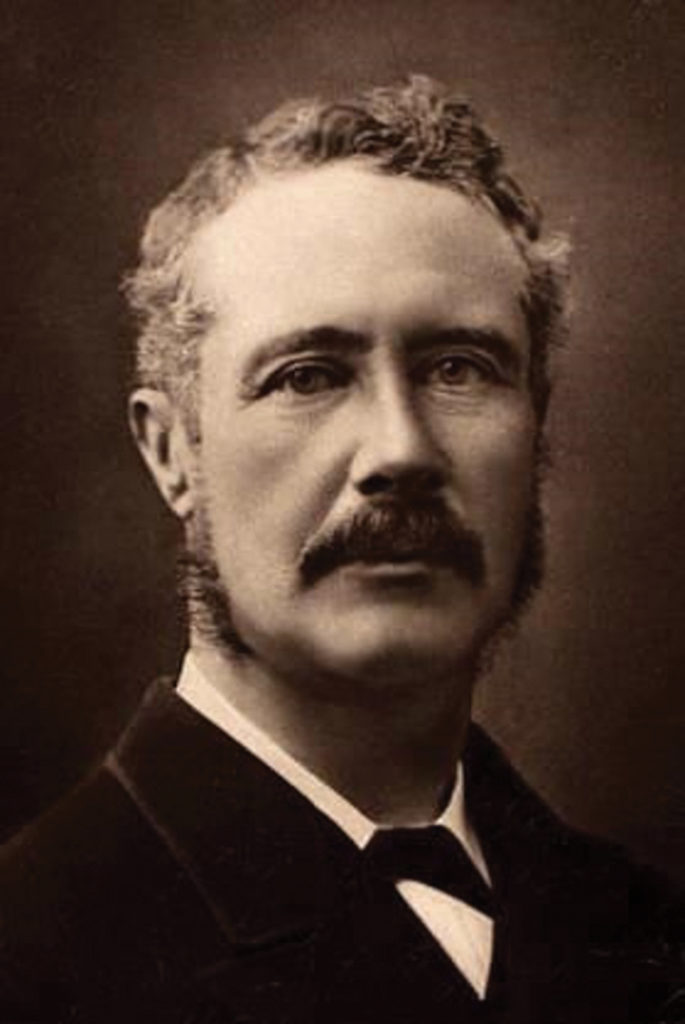

In an attempt to crush the insurrection and free the prisoners, the government decided to intervene with a mighty army, led by British General William Hicks. On 9 September 1883, 10 000 men, including infantrymen and cavalrymen, and 6 000 camels to transport ammunition and provisions, rifles and cannons, left Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, but “that great mass of Muslims led by a cosmopolitan Christian general of staff” (Gozzi 2010) had the seeds of defeat in it. Hicks did not know the region and relied on two fake deserters from the Mahdi, who led his army into an ambush. After two days of fighting, only a few hundred men survived. Charles Gordon, an anti-slavery British officer who had been governor of the Equatoria region from 1873 to 1876, was appointed governor of Sudan. Supported by Martin Ludwig Hansal, the Austro-Hungarian consul in Khartoum, he tried to negotiate with the Mahdi for peace and the release of his prisoners.

The capital falls

In April 1884 the Mahdi’s troops left El Obeid, concentrated in Rahad and began to march towards Khartoum. The British government was slow to send reinforcements and the Sudanese capital fell on 25 January 1885. Gordon and Hansal were slaughtered along with another 2 000 people. In a few years, the Mahdia controlled almost all of Sudan, but on 22 June 1885, Muhammad Ahmad died of typhus. He was succeeded by Caliph Abdullahi ibn-Muhammad. In this context, the conditions of those in captivity became dramatic, especially for the nuns, whose state of life was not contemplated in Islam. The difficulties became worse in 1889 due to a terrible famine that decimated the population of the entire Mahdist state, mainly due to years of war that deprived agriculture of its workforce.

“And this is the story, or almost the story, of all of them: how many lashes! The formula was taken when we were almost exhausted and out of our senses from the anguish, beatings and hunger, and half-dead. We shivered at the thought that the Mahdi would divide us among his leaders,” “And this is the story, or almost the story, of all of them: how many lashes! The formula was taken when we were almost exhausted and out of our senses from the anguish, beatings and hunger, and half-dead. We shivered at the thought that the Mahdi would divide us among his leaders,” (Teresa Gregolini in Maccari 1988)

The uneasiness among the population aggravated the tensions that had already emerged in the Mahdi’s succession and weakened the Islamic State, which in 1896 began to crumble in the face of General Herbert Kitchener’s military advance. On 7 April 1898 the Anglo-Egyptian army defeated a Mahdist army on the Atbara River and on 2 September 1898, conquered Khartoum.

The account of the witnesses

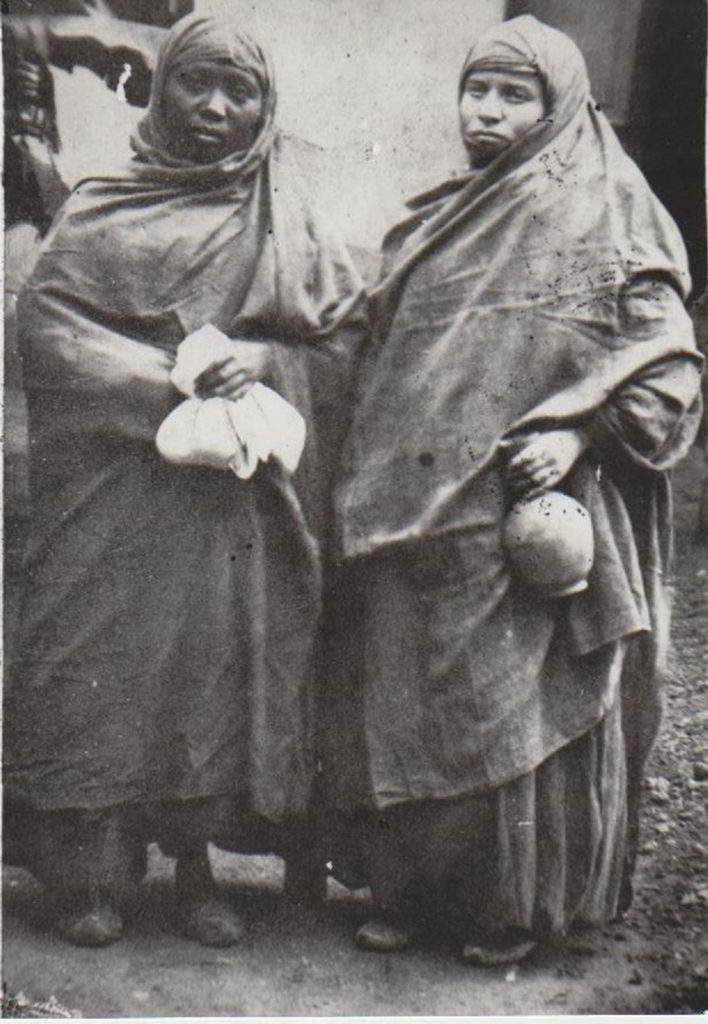

When the insurrection led by Muhammad Ahmad reached Kordofan, the Catholic missions became an important target: the staff, besides being Christian and of European origin, openly opposed slavery and gave shelter to those who fled from it. “Being a ‘woman, white, Christian’, and moreover unmarried, was a great challenge for every sister (Archive Madri Nigrizia 2011).

Those who remained in captivity suffered more repression because of the escape of the others, but those who returned to the community after years of unimaginable suffering also suffered

“The experience they were forced to live throughout their captivity was deeply traumatising, not only because they were foreigners and Christians, but above all because they were women, and consecrated women”, stresses Sr Maria Vidale (Archive Madri Nigrizia 2011).

From joy to tears

Easter Sunday on 9 April 1882, was a day of celebration in El Obeid; the Nubian, Fortunata Quascè, a former slave educated in Verona at Mazza Institute, became the first African Pious Mother of Nigrizia (Comboni Sister). A few months later, the city was destroyed by the Mahdi’s troops.

Teresa Grigolini, in charge of the sisters in Sudan, was worried; no news came from the mission in Delen and the Mahdi troops were marching towards El Obeid. It was urgent to leave: “We are in an unspeakable turmoil, we have packed our trunks to return to Khartoum, but the government is denying us the soldiers to accompany us,” she writes from that mission. With no reliable communication, the course of confusing news became an agony. She tried to convince Fr Giovanni Losi—acting superior while waiting for Daniel Comboni’s successor—to leave, but he delayed. He hoped that the staff from Delen would arrive, but they had already been made prisoners; so when Fr Losi decided to leave it was too late.

Siege and starvation

In August 1882 the population of El Obeid was invited to take refuge in the fortress. The nuns were hosted by a former slave girl, Marietta Maragase, and the male staff by Syrians. On 8 September, the first attack was repulsed by the garrison, equipped with cannons and rifles. If the Egyptian battalion would have exited the fortress to persecute the Mahdist troops during their withdrawal, perhaps these would have been defeated; but this did not happen and El Obeid fell, due to starvation after five months of siege. Teresa Grigolini recalls: “The poor, very numerous, were the first to die. The quarters were all cluttered with mats and rags, the little ones dying of hunger; skeletons stretched out their hands to ask for charity and died in that position.” In the meantime, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception was approaching and the sisters were ready to renew their vows, but Fr Losi did not allow them to do so and suggested to them to renew their “private vows” daily or every 15 days. Scurvy raged and Fr Losi himself died from it.

On 16 January, the Mahdi demanded the surrender of the fortress, still full of ammunition. The governor would have preferred to blow it up with the powder keg, but the officers refused to obey him to preserve their families, and on 19 January, the Mahdi conquered El Obeid with its weapons. Elisabetta Venturini recalled: “As soon as they went inside, like so many raging beasts, they took the (African) boys and girls we had with us. Then they went to Fr Rossignoli and Brother Locatelli; they threatened them that if they did not become Muslims they would have their heads cut off. They were immediately intimidated and abjured without the slightest resistance.” The nuns, despite slaps and beatings, refused: “we were left alone: we were Teresa Grigolini, the superior, Concetta Corsi, Caterina Chincarini, Fortunata Quascè and Elisabetta Venturini.”

In the Mahdi camp

Threatened and beaten, they were dragged before the Mahdi: “After so many flatteries and promises,” continued Elisabetta, “finding us as strong as before, he told us that the Lord would forgive us now and later we would see the truth.” The five sisters were reunited with the survivors of Delen: “Being together again after so many misfortunes, it seemed like a dream. One should see in what state we found them.”

“We stayed like this for about a year,” Teresa recalled, “spending our lives suffering and praying always in great trepidation for the future.”

In fact, attempts to free the missionary personnel continued for months, but were unsuccessful. They hoped for military action entrusted to General Hicks, but this failed tragically. A ransom was offered, which the Mahdi categorically refused, and a plan to escape was contemplated. A Syrian, formerly the mission’s procurator and now Mahdi’s ‘lieutenant’, provided the camels and everything was ready for 29 March 1884. On the eve of that day, the unexpected happened: “The Caliph Abdullahi appeared suddenly with a large retinue in front of our house and summoned Fr Bonomi, myself and Brother Giuseppe Regnotto,” wrote Fr Giuseppe Ohrwalder. “The sun had just disappeared when we saw about 30 satraps coming on horseback, declaring that they had orders to take the nuns away.”

Heroic weakness

It was night. They took the nuns to a hut near the Mahdi’s compound, and the next day began the interrogation repeated insistently until evening: “Do you want to become Muslims?” We answered that we were Christians and intended to die as Christians,” Elisabetta Venturini recalls. In the middle of the night, Caliph Abdullahi arrived with three of his men. Seeing that after so many questions they could get nothing, they took Sr Fortunata aside, tied her to a pole and whipped her until they were tired.” Then they raged on Teresa Grigolini, cutting off her lips. The long-awaited escape turned into a torture that continued for days. “Not being able to kill us, they vented their anger by dividing us up,” which happened on 1 April 1884, before leaving for Rahad. Each one was handed over to the women of the leaders who, amid threats and promises, continued to try to convert them “saying that we were lucky because the Mahdi and the Caliph loved us and would have married us if we had become Muslims. Imagine what happiness!” Don Luigi Bonomi states: “The usual threats and intimidations were renewed, and even more so to the sisters; the example of their heroism was for us the object of the highest admiration.” The Mahdi had in fact given orders to convert all the mission staff to Islam, but not to kill them.

Exhausted and unconscious

From El Obeid to Rahad, the sisters walked almost 60 km barefoot, without food and under a blazing sun. One evening, Sr Concetta, destined for the harem of Caliph Abdullahi, was attacked by two men who tried to rape her. Her cries attracted attention and they fled, but she was exhausted and asked for an audience with the Mahdi. It was 12 April 1884. To be admitted into his presence she had to pronounce the formula of adherence to Islam. The news spread immediately: a nun had succumbed. Teresa Grigolini understood the cause and decided to join her sister: “I was the second one brought before the Mahdi, and there I met Sr Concetta.” After days of threats, Elisabetta also left for Rahad in the retinue of Caliph Ali Dinar. To bend her will, they beat her repeatedly under the feet and dragged her with a rope around her neck during the journey; she did not give in, so they tied her to a tree and beat her for hours until they believed she was dead. The Mahdi then demanded that she should be taken to his house, where there were already four nuns. Maria Caprini, a veteran of the mission in Delen, also arrived. “After 40 days since our separation we are all united again, but what a painful and terrible reunion; in the house of the Mahdi! It seems to people that we have all become Muslims, but it is not true,” Elisabetta Venturini narrated in her memoirs, while for the European press they had all already become Muslims, except for two priests and three nuns.

Marriages to be made

The Mahdi announced to the six nuns that as Muslims they must marry. Teresa manages to let Fr Bonomi—still in prison— know this and at the end of June she is joined by Rudolf Slatin, a former government official and friend of the mission. With him were other ‘converts to Islam’: Isidoro Locatelli and some Greeks led by Dimitri Cocorompas. While waiting for their release, in order to prevent the nuns from being given in marriage to Muslims, Slatin persuaded the men to contract apparent marriages with them, which were officially contracted that same night in front of a Muslim representative. Teresa Grigolini was at Cocorompas’ house; Concetta Corsi, at Isidoro Locatelli’s; Caterina Chincarini, at Trampa’s; Fortunata Quascé was at a certain Andrea’s. Maria Caprini and Elisabetta Venturini were spared because they were already too weak from torture.

Everyone has found his liberation. The nuns in their convent, and all the others in their families and countries; I alone could find neither my convent nor my family, and my slavery would last until my death

In August 1884 the Mahdi, leaving Rahad, marched towards Khartoum but one of his caliphs, with Frs Bonomi and Ohrwalder in his retinue, was sent to El Obeid to govern Kordofan. So the six nuns stayed with their fake husbands and after five months walking they reached the Mahdist troops’ camp in Omdurman. An area was reserved for the ‘renegades’, those who had ‘forcibly’ converted to Islam after being captured; they lived under surveillance and had to provide for themselves. The clear separation between men and women, typical of that culture, facilitated the co-existence of the four sisters with their ‘husbands’, who worked at the market from morning to evening: “They sell some cotton cloth, some jackets that we sew at home and some other things. At midday we prepared lunch for everyone and sent it to Fortunata’s hut and there the men ate alone and we ate alone, according to the custom of the country”, read Teresa Grigolini’s Memoirs.

Waiting for liberation

Monsignor Sogaro, Daniel Comboni’s successor, tried in every way to organise the escape of all missionaries. An Arab reached Omdurman and delivered a message to Teresa Grigolini, but he was arrested as an English spy. Khartoum was under siege and fell on 25 January 1885. The messenger was liberated and, on 3 February, he managed to get Teresa Grigolini’s messages and reached Licurgo Santoni, in Dongola, an Egyptian postal official, in contact with Monsignor Sogaro. Teresa asked that all of them would be able to escape from Omdurman together, and specified that in Kordofan there were Frs Bonomi, Ohrwalder, Rossignoli and Regnotto: “Here in Omdurman there is Isidoro Locatelli, Domenico Polinari with six nuns: Concetta Corsi, Caterina Chincarini, Marietta Caprini, Elisabetta Venturini, Fortunata Quascè and Teresa Grigolini, all in good health. In order to avoid horrendous dangers, we the sisters are divided into three houses under the protection of three Greeks who do the charity of keeping us hidden by sharing the meagre bread with us.”

The letter was leaked to the press and created a great impression. Sogaro replied: “Passing as the wives of some Greeks was an industrious ruse; their behaviour was beyond praise.”

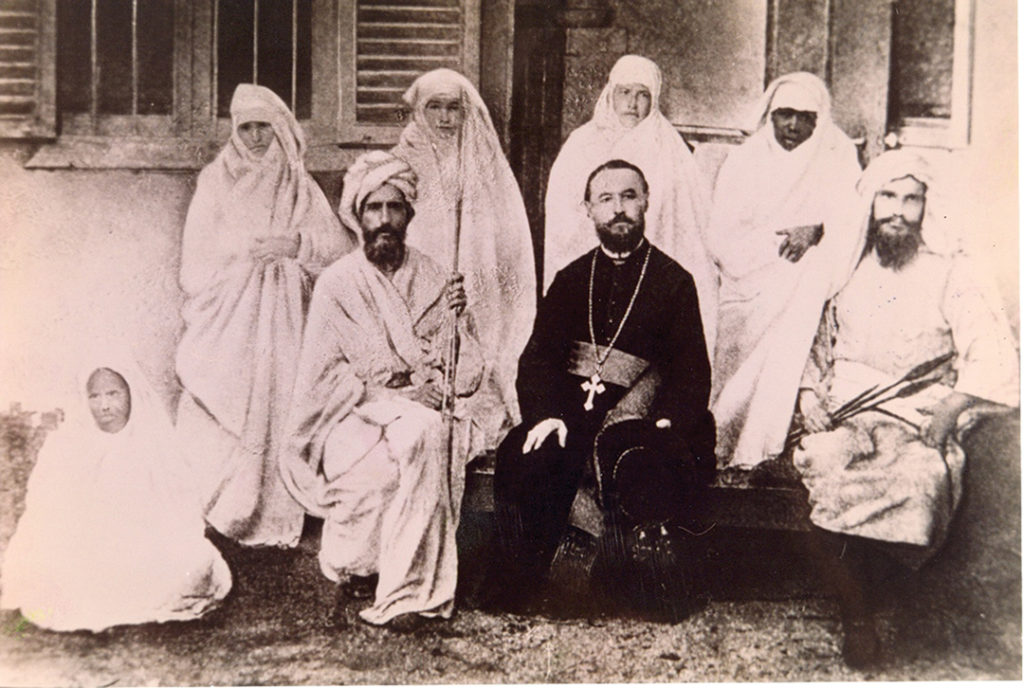

on his right, Fr Giuseppe Ohrwalder. Cairo, 1891.

Finally on the run

The first to escape was Fr Bonomi, on 25 June 1885, from El Obeid; followed, on 7 October, by Maria Caprini and Fortunata Quascé from Omdurman. They were all supposed to leave, but the messenger arrived with 16 camels when Concetta, raped by Locatelli, was pregnant and Teresa chose to stay with her and Caterina, who for health reasons could not endure days and days on camelback. Elisabetta, hosted at Cocorempas’ house and threatened by the Caliph to be given in marriage, had tried to escape on her own during those months. In 1886 Fr Ohrwalder arrived in Omdurman and officiated the marriage between Concetta and Isidoro in a Christian ceremony, but Isidoro fled at the beginning of 1887, leaving her with their young son. The other false husbands struggled to continue the charade and asked for money to maintain the nuns and not do violence to them.

She remains alone

From the end of 1888, famine raged in Sudan and, even in the ‘renegade’ neighbourhood, survival became difficult. Desperate, Teresa asked her brothers for help in 1889. The letter reached them in August and aroused indignation towards the Institute, which had abandoned the sisters, and increased the misunderstandings between it and those waiting for help.

To dispel the suspicion of a sham marriage with Cocorempas, Teresa herself was forced to marry in August 1890. On 3rd October 1891, Concetta died of typhus.

On 29 November, however, Elisabetta, Caterina and Fr Ohrwalder were finally released. The flight was strenuous, to the point that an exhausted nun fell off the camel. On 21 December they finally arrived in Cairo. On this occasion, Sogaro wrote to the Vatican: “The former Superior Teresa Grigolini was married to a certain Greek, Dimetri Cocorempas. There are, however, very serious reasons for not having to condemn her conduct; a victim all the more worthy of compassion, in that she was always of blameless innocence and exemplary character.”

The cost of martyrdom

Those who remained in captivity suffered more repression because of the escape of the others, but those who returned to the community after years of unimaginable suffering also suffered. Maria Caprini and Fortunata Quascè remained marginalised for a long time; Caterina Chincarini and Elisabetta Venturini were considered apostates, and Fr Ohrwalder was even asked to make a profession of faith in order to reinstate him as a priest. The most painful situation, however, was experienced by Teresa Grigolini Cocorempas. The mission tried several times to organise her escape, but as she was often pregnant, she could not escape. For her, liberation came on 3 September 1898, after the victory by Kitchener: “For a whole year I mourned my fall, but even more so on the day of liberation. Everyone, I said to myself, has found his liberation. The nuns in their convent, and all the others in the bosom of their families and their countries; I alone could find neither my convent nor my family, and my slavery would last until my death,” she wrote in her Memoirs.

| Dates To Remember |

|

June 1 – Global Day of Parents 4 – International Day of Innocent Children Victims of Aggression 5 – Pentecost Sunday 5 – World Environment Day 8 – World Oceans Day 12 – World Day Against Child Labour 13 – International Albinism Awareness Day 15 – World Elder Abuse Awareness Day 16 – National Youth Day in South Africa 17 – World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought 19 – International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict 20 – World Refugee Day 23 – International Widows’ Day 26 – International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking 27 – Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Day July 3 – International Day of Cooperatives 11 – World Population Day 15 – World Youth Skills Day 18 – Nelson Mandela International Day 24 – World Day of Prayer for Grandparents and the Elderly 30 – International Day of Friendship 30 – World Day against Trafficking in Persons |

Hi! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any problems with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing a few months of hard work due to no data backup. Do you have any methods to prevent hackers?