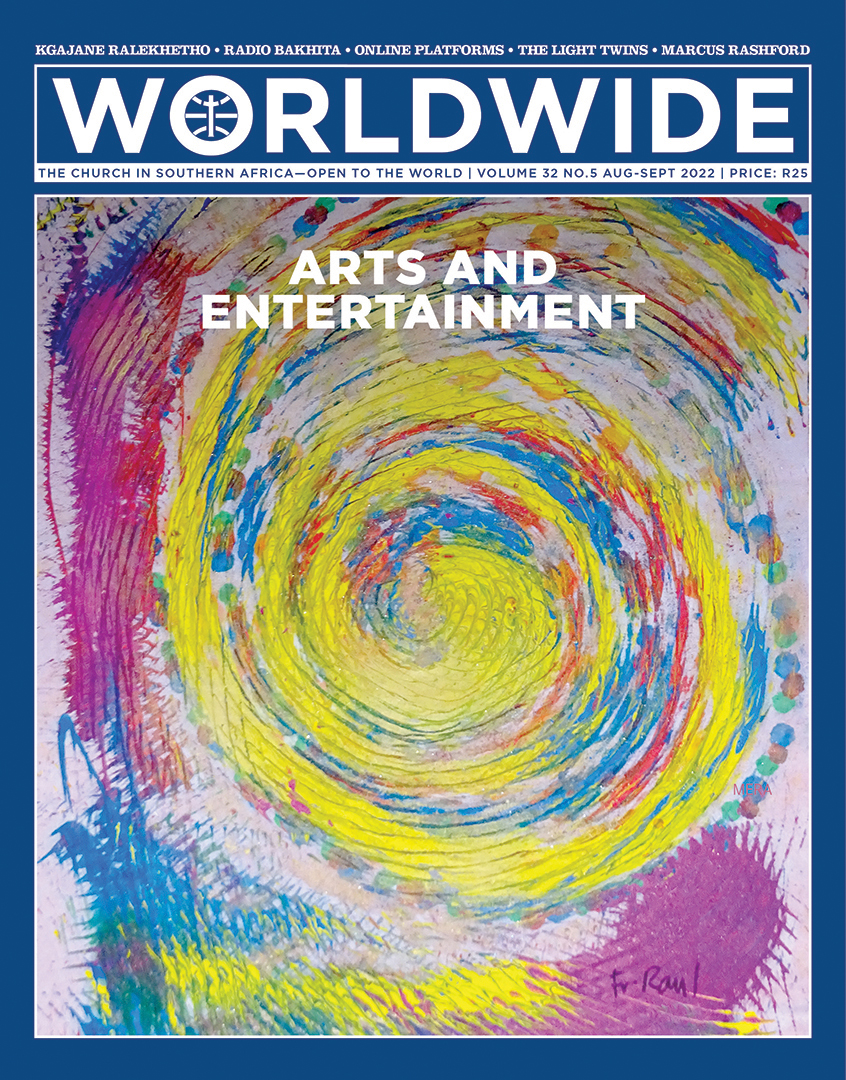

ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT

This painting represents the turmoil experienced during a time of crisis. Typhoon is a symbol of anxiety, chaos, destruction and struggle. However, once those trial moments are surmounted, the inner energy of the typhoon brings transformation, putting life in order and strengthening one’s spirit. Emotional typhoon seems to tear life apart when it hits. One can’t turn away from it, but once it is over, it brings new potential; visions become clear and one sees brighter days ahead.

PAINTING BY FR RAUL TABARANZA MCCJ

INSIGHTS • SOCIAL MEDIA

Empowering people’s politics?

BY MIKE POTHIER | PROGRAMME MANAGER, SACBC PARLIAMENTARY LIAISON OFFICE

A LOT has been written about how social media has undermined the powers of oppressive governments, and strengthened the voices of ordinary people. When the Arab Spring—the popular uprisings against undemocratic regimes in North Africa and the Middle-East—swept various dictators from power in the early 2010s, it was claimed that Facebook, Twitter and similar platforms were crucial in mobilising people, co-ordinating protests, and keeping the momentum going.

But the same platforms can be used for destructive purposes. Here in South Africa, when President Jacob Zuma was sent to prison last year his supporters used social media to orchestrate the riots and looting that so badly affected KwaZulu-Natal and parts of Gauteng. Likewise, every party congress or internal election sees millions of messages, for or against certain candidates, flashing from phone to phone across the country—some of these may contain helpful information, but many are simply an attempt to shout up one side and drown out the other.

There is also the problem that governments know very well how to use social media for their own purposes. In Russia, for example, social media channels are being employed to spread huge amounts of misinformation—‘fake news’—about the invasion of Ukraine. Repressive states can track social media messaging as a way of keeping tabs on activists, and of building up evidence against them.

They can also simply switch off, or ban, platforms they don’t like. The internet is regularly blocked by regimes which don’t want their people to have access to certain kinds of information. Facebook is banned in Iran and North Korea, as well as China—which also bans YouTube, Instagram, WhatsApp and a host of others.

So, in the political world, social media is on the one hand, obviously a tremendously powerful tool for sharing information and organising people; but on the other hand, most platforms are pretty much as vulnerable to state interference as older, pre-digital age communications were.

Another limitation is that, while social media is great for immediate communication and for spreading messages, it doesn’t necessarily help to build structures. Genuine political organising needs time, hard work and commitment. After all, it is about service—or at least, according to Catholic Social Teaching, it should be. There is a saying along the lines that it is all very well signing an online petition, or re-tweeting someone’s clever comment, but if this is all you do nothing will change.

While social media is great for immediate communication and for spreading messages, it doesn’t necessarily help to build structures

This brings us to perhaps the biggest danger with social media in politics—that it encourages superficiality and promotes simplistic approaches to complex issues. The most notorious tweeter in politics was probably Donald Trump (before Twitter banned him for continually lying about his 2020 election loss). Firing out dozens of tweets every day, many of them personal attacks on his rivals and anyone who happened to disagree with him, may have delighted his supporters, but it certainly didn’t help them to understand the issues. It also failed to give them any sense of the nuances and grey areas that are almost always present in political debates. On Twitter and many other social media platforms, things are simply black or white, right or wrong.

Our own Helen Zille has fallen victim to this tendency on more than one occasion. Her infamous tweet about the benefits of colonialism was a case in point, as was her tweet about ‘economic refugees’ coming to Cape Town from the Eastern Cape. In both cases she tried to squeeze complex arguments into Twitter’s 140-word format—and it didn’t work. It’s a bit like reading someone’s short-hand notes—only the writer knows what they really mean.

So, as with any form of technology, social media can be used with good or evil intentions, and its results can sometimes be quite the opposite of what was expected. Will it really transform our way of doing politics? Will it reduce the power of professional politicians and give more influence to us ‘ordinary’ people? Maybe—but it is worth noting that none of the countries that experienced the Arab Spring have yet become stable democracies. Social media may have gone some way to initiating the spring, but it could not, by itself, bring in the summer.