WORLD REPORT • GLOBAL AND SOUTH AFRICAN OVERVIEW

Credit: photo by PxHere.

The State of our Waters

“If a bucket contained all the world’s water, one teacup of that would be fresh water, and just one teaspoon of that would be available for us to use, from lakes, rivers and underwater reservoirs as groundwater” (Dr James Jenkins, University of Hertfordshire in Beneath the Surface: The State of the World’s Water 2019. Water Aid).

BY

Leevonia Ussi

| Journalist

Dr Rudo A. Sanyanga Hungwe | Freshwater Ecologist, Pretoria

THE EARTH, referred to as the “blue planet”, has more water than land, 70% and 30% respectively. In 1969, when Neil Armstrong landed on the moon, he described her as “a shining blue pearl spinning in space”—the blue being the earth’s surface water.

Freshwater resources are essential for all forms of life; they support ecosystems and contribute to civilization. Despite its importance, fresh water is an extremely limited resource. It makes up only 2.5% of the earth’s surface water, with saltwater constituting the other nearly 96.5%. Of this 2.5%, less than one third—coming from lakes, rivers and swamps—is available for human use; the rest is locked in the form of ice, glaciers and polar caps.

Despite its importance, fresh water is an extremely limited resource

Another vital source of fresh water is groundwater aquifers. They account for 99% of all liquid fresh water on earth and a quarter of all the water used by humans. Groundwater provides 50% of global urban domestic water—the other half comes from rivers and lakes—and around 25% of agricultural irrigation water.

When water comes out of a tap, there is no telling of its source and the processes undergone to reach its destination. For most urban dwellers, to get clean water out of the taps means raw water has undergone processes of storage, abstraction, and treatment, before distribution, at an immense financial cost and energy, and complex infrastructure is used.

Global freshwater resources

Globally, the agricultural sector uses 70% of the fresh water, with 25% coming from underground aquifers. Agricultural activities are crucial to feed the earth’s 8 billion inhabitants, employ over a billion people and generate over US$ 2.4 trillion per year.

As populations grow, the demand for food increases and more irrigation is needed. Half of the world’s wetlands have been converted into cultivated land, reducing natural habitats for animals and plants. The Indian Green Revolution of the 1960s was important in lifting the country out of poverty and food insecurity, owing much to crop irrigation, which relies mostly on underground water resources. Unfortunately, decades of overexploitation on irrigation have led to low levels of underground water, particularly in some regions in Pakistan, India and California in the USA.

While irrigation consumes the largest share of fresh water locally and globally; it also wastes approximately 60% of it through leaky systems, inefficient application methods and cultivation of thirsty crops. The unsustainable water abstraction levels from rivers and lakes have contributed to the drying up of freshwater bodies; with current examples being the Aral Sea in central Asia and Lake Chad in West Africa. The Aral Sea, once the 4th largest freshwater lake, is now a very small and salty water body.

According to the United Nations, approximately 2.1 billion people in the world lack access to clean drinking water; one billion of them in Sub-Saharan Africa, or about 70% of its population. Seventy-four percent of the global population have adequate access to safe drinking water, the majority being in Europe, Australia, and the Americas.

South Africa’s water situation

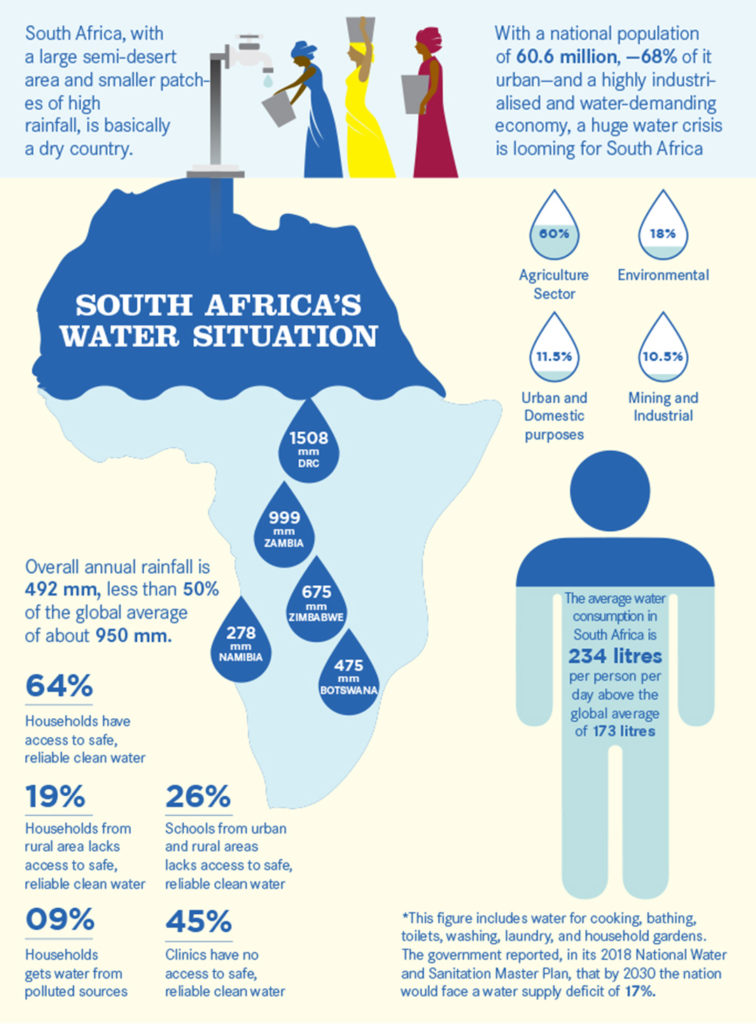

South Africa, with a large semi-desert area and smaller patches of high rainfall, is basically a dry country. Its overall annual rainfall is 492 mm, less than 50% of the global average of about 950 mm. The dryness of South Africa becomes starker when compared to the average rainfall of countries in the region, such as Zimbabwe (675 mm), Zambia (999 mm), and DR of the Congo (1508 mm); being only higher than Botswana (475 mm) and Namibia (278 mm). With a national population of 60.6 million, —68% of it urban—and a highly industrialised and water-demanding economy, a huge water crisis is looming for South Africa. At present, the agriculture sector consumes 60% of the water, and the rest is for environmental (18%), mining and industrial (10.5%) uses and 11.5% for urban and domestic purposes. The average water consumption in South Africa is 234 litres per person per day, above the global average of 173 litres. This figure includes water for cooking, bathing, toilets, washing, laundry, and household gardens. The government reported, in its 2018 National Water and Sanitation Master Plan, that by 2030 the nation would face a water supply deficit of 17%.

Water scarcity is worsened by the country’s ageing infrastructure and poorly maintained supply systems, pollution, growing demand and climate change. While 64% of households have access to safe, reliable clean water, 9% get water from polluted sources. Rural populations are worse with 19% lacking access to a reliable water supply. Worse still, over 26% of schools (urban or rural), and 45% of clinics, have no access to safe water.

In urban centres, 37% of treated water is lost through leaks and pipe bursts. Experts estimate that R1 trillion or more is needed to recapitalise the water sector in South Africa.

The quality of water in rivers, dams, lakes and aquifers is conditioned by human activities in their catchment areas

The distribution of water is very uneven, costly and brings other challenges. Millions of people, especially in Gauteng, drink water captured in reservoirs situated more than 400 km away. Gauteng’s water comes from the Vaal fed by two transfer systems, namely the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, and the Tugela-Vaal Water Transfer Scheme, from Kwa-Zulu Natal. Water transfer schemes are costly and alter the water quality. As water flows, it collects pollutants, evaporates and is stolen, apart from the cost of maintenance of the conveyance infrastructure. Gauteng water demands may sooner or later outstrip supply.

Pollution

Water pollution occurs due to harmful substances—often chemicals or microorganisms—which contaminate a stream, river, lake, ocean or aquifer, rendering it unsuitable for human consumption. Most of the supply sources in South Africa are under threat from pollution, becoming a major issue in the country and reducing the amount of available water. All sectors pollute, but agriculture, industry and mining are the main ones. Mining has been polluting groundwater sources for a long time—and still does, rendering some of the aquifers’ water undrinkable. Experts estimate that nearly half of the country’s water bodies are polluted.

Polluted water is dangerous to plants and animals. It affects people’s health, particularly for those who get it directly from a river or dam. The United Nations reported that globally 3 million deaths occur annually due to a lack of access to clean drinking water. People, who rely on contaminated water sources, face higher risks of diarrhea, cholera and dysentery, among other diseases, and in babies, genetic deformities, due to heavy metal pollutants. Polluted water is expensive to treat, as large amounts of chemicals are needed to bring it to potable quality. Urban dwellers have to pay this extra cost to municipalities.

The quality of water in rivers, dams, lakes and aquifers is conditioned by human activities in their catchment areas. Agricultural chemicals and fertilisers, and any other polluting or erosion-promoting activities will lead to poor water quality. Integrated catchment management is important to ensure healthy rivers and reservoirs.

Climate Change

Approximately 4 billion people world-wide live in areas experiencing water scarcity, with experienced shortages at least one month per year. Global warming, accelerated by human activities, affects rainfall patterns. Floods and droughts are now more frequent throughout the world. In polar regions, glaciers and icepacks are disappearing, with a devastating impact on freshwater supplies in the downstream regions which traditionally relied on them.

UNESCO reports that one third of the glaciers in the world, including the Swiss Alps and Yosemite National Park in the USA, will melt away in the next decades due to climate change. The glaciers that cap Mount Kilimanjaro will vanish by 2050.

In the last five years, South Africa has experienced droughts, fires and floods, costing human lives and causing huge destruction to infrastructure. Climate experts predict much wetter rainy seasons and drier winters, causing floods and droughts. Therefore, the nation must put in place strategies to mitigate climate impacts and improve its management of freshwater resources.

Conserving water and geopolitics

In order to meet the need for fresh water, both for people and ecosystems, water conservation is crucial; consciously limiting consumption, avoiding waste and recycling or re-using water as much as possible. This is all based on lifestyle changes.

Every individual can conserve water following simple domestic habits; such as turning off the tap while brushing teeth or shaving, running full loads of clothes when doing laundry, positioning sprinklers correctly in the lawn and garden, planting native shrubs and groundcovers less demanding in water compared to other exotic plants, allowing the lawn to rest for a few months, making compost out of food waste and applying it to the garden for better water retention, repairing leaking taps and pipes, upgrading to more water-efficient appliances, harvesting rainwater from rooves and re-using it to water gardens and rinsing vegetables in a dish of water instead of under a running tap.

World population growth is putting a huge strain on limited resources increasing competition for water. In transboundary rivers, lakes, and other bodies, higher water demands by an upstream riparian nation often leads to heightened insecurities for downstream countries which sometimes degenerate into conflicts. One of the examples is the dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia concerning the use of the Nile River water.

With the myriad of issues and threats to our freshwater resources, there is a need to educate, protect and conserve our water. The agricultural sector could address the water crisis with a world-wide reform. Mines require innovations to use less water and to be regulated to avoid surface and groundwater pollution. We all need to act now!