SPECIAL REPORT • XENOPHOBIA

THE PERVASIVE DISREGARD AND VIOLATION OF HUMAN DIGNITY

Xenophobia, as a pervading attitude, erodes human dignity. Conversely, a sense of humanism respects every person’s right to build a future in peace and freedom

BY RAMPE HLOBO SJ | CHAIRPERSON OF MIGRATION COMMISSION OF THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN PROVINCE OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS, JOHANNESBURG

SINCE THE unceremonious expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden and the obedience of Abraham to God’s call to leave his home for a foreign land as narrated in Genesis 3 and 12, respectively, migration has been part of human existence.

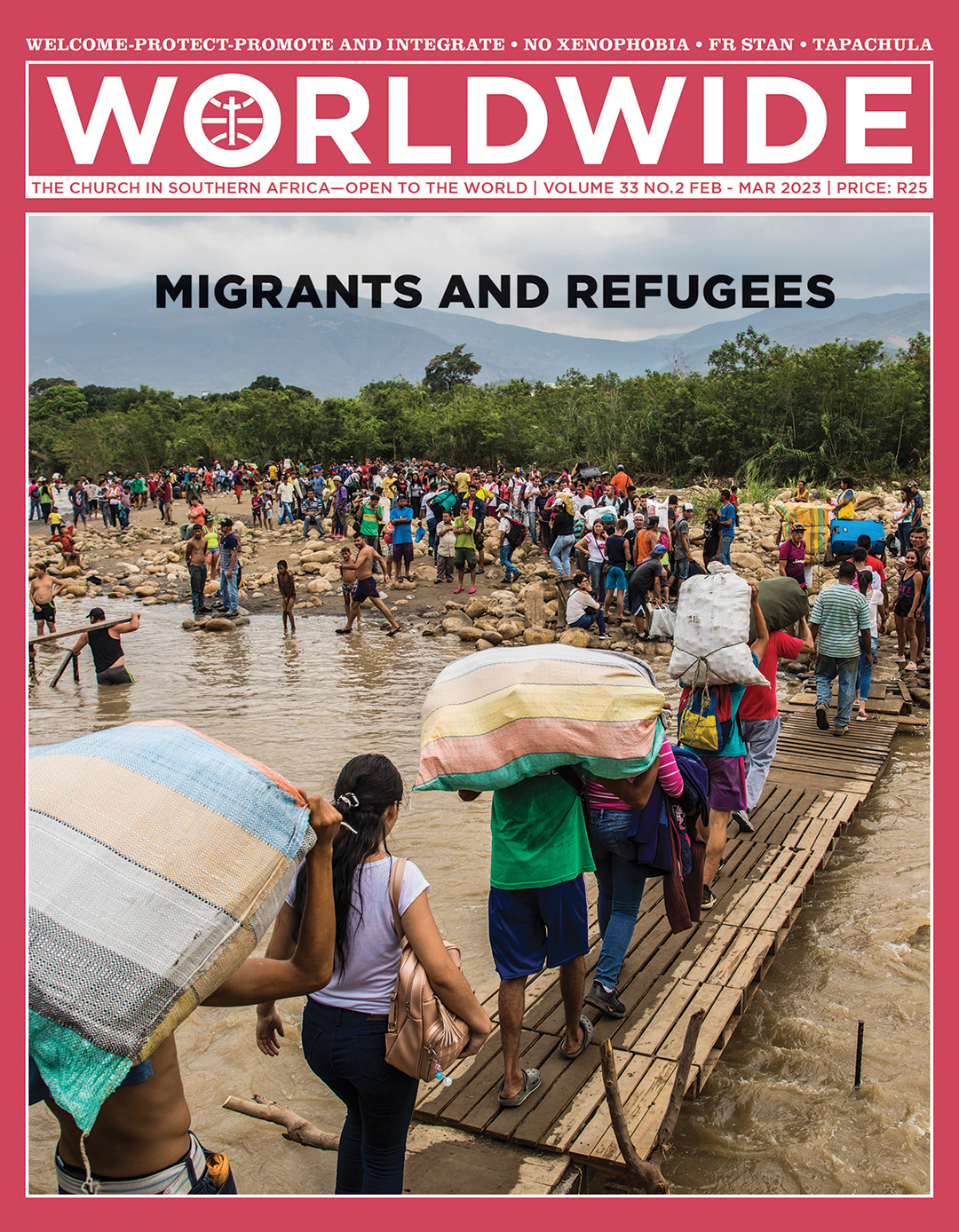

The twenty-first century has seen the number of people living away from the place they would call home, rise to a staggering 290 million. Many of them—because of the economic imbalances and unfair distribution of resources—have been forced to go and seek greener pastures away from their provinces or countries. Many more—41% of whom are children—have been forced to flee because of extreme weather patterns, human rights violations or wars. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), by the end of 2021, just over 89 million people were forced to abandon their homes due to conflicts, violence, fear of persecution and violations of human rights. Six months later that number had risen to over 100 million.

These statistics may often make one numb and subsequently lead to a disregard for the fact that these are not just statistics, but human beings with their dignity; men, women and children forcibly displaced, who experienced calamitous social, political and environmental circumstances which threatened their welfare, their lives, their very humanity and inherent dignity.

This indifference toward intrinsic human dignity—emanating from the belief that we are created in the Image of God (Imago Dei), has, in most instances, led to many being treated as subhuman. In many countries, in which migrants and forcibly displaced persons live, there is an inordinate and reprehensible hyper-allegiance to religious or cultural communities which wrongfully justify the corroding of respect and human dignity due to non-nationals. This attitude has led to some individuals responding unfavourably to the critical needs of their fellow human beings, simply because they come from across the border or are of a different nationality.

Despite the many calls, by religious leaders and people of goodwill, for solidarity with migrants and the forcibly displaced, especially the vulnerable ones, many only find hostility and limited tolerance if any. The number of incidents of violence, sometimes even fatal attacks against non-nationals—just for being foreigners—has become frighteningly high. These instances of xenophobia, have been carried out by individuals, communities, social groups and institutions, including those that are legally and morally obliged to protect the victims. Often, these deplorable reactions, which are almost always targeting black Africans, have been widespread and unfortunately manifested in both violent and non-violent forms.

Xenophobia in South Africa

South Africa—the El Dorado of the African continent and for a long time a magnet for migrant workers, especially mine workers, has been notoriously labelled the most xenophobic country on the continent. When it comes to violence against nonnationals, it is probably among the worst in the world. Since that notorious 1998 incident, when a Mozambican and two Senegalese were thrown out of a moving train for being foreigners and blamed for the rising unemployment rate and many

other social ills, violent xenophobic attacks have been on the rise in South Africa. Regrettably, with the high level of impunity and a general perception of non-nationals as the source of rampant unemployment

and other social ills, the problem continued and, a decade later, in May 2008, South Africa experienced one of the most barbaric and unspeakable xenophobic riots in the post-apartheid period, starting in

Alexandra, Gauteng and then spreading to other locations across South Africa, causing at least 62 deaths.

Although many migrants and forcibly displaced persons from other countries, especially African countries, have experienced horrendous and violent hostilities in South Africa, it is equally noteworthy that the problem of xenophobia is not unique to South Africa. Nevertheless, what

seems to be generally distinctive to South Africa is the high level of violence with which these incidents are carried out and the accompanying fatalities. Furthermore, thanks to tracking structures, freedom of the press and an active and vigilant civil society, xenophobic cases in South Africa are mostly detected, documented and reported. Agencies such as Xenowatch have been excellent in making statistics

and facts on xenophobic incidents readily available for anyone concerned or interested. This practice, however, is lacking in many African countries. Hence there are few if any records or documentation of xenophobic incidents in them.

Afrophobia

Numerous other African countries have been found wanting when it comes to migrant and refugee reception and protection. Contrary to the popular belief that Africa is a hospitable continent, there is enough empirical evidence, dating as far back as the 1960s, to prove the opposite. One example that stands out is the hostility that many Ghanaians and Nigerians harbour for each other. This probably stems from the expulsion of the Yoruba migrants from Ghana in 1969 and

the infamous 1983 expulsion by Nigeria of two million allegedly undocumented migrants, half of whom were apparently Ghanaians. Since then, there seems to be no end in sight to the love-hate relationship between the two West African countries. That 1983 incident led to the popular, movement nicknamed ‘Ghana must go home.’

Experience and reports show that many other countries are struggling with lowlevel or physically non-violent xenophobic incidents and inhospitable sentiments towards foreigners as well. In 2020, Voice

of America reported that Egyptians were found to be not only hostile to Ethiopians living in Cairo, but the Ethiopians also complained about the intensifying incidents of racism they were experiencing. Many Africans have for a long time enjoyed refuge in Egypt, but in recent years many have complained about the rising racist harassment and even violence that Libyans and Syrians do not necessarily experience.

The Egyptian context is not totally unique in the Afro-Arab world. Morocco is another country where African migrants have experienced unspeakable hostility and racism as well. Tensions of inclusion and exclusion, based on nationality and or race, have been a prominent feature in many countries, notably in South Africa, Egypt and Morocco. Chad Williams (2022), a journalist of IOL News, reported that a World Population Review, recently published in May 2022, described Africans as fairly racist towards one another. Consequently, this hostile bigotry has fueled conflicts which subsequently have become the root cause of further forced displacement.

Some countries, with their ‘encampment policies’, have deprived asylum-seekers and refugees of the dignity and freedom of movement, and consequently their livelihood activities as well. Xenophobia and hostile sentiments are widespread across the African Continent and it is a challenge that needs to be dealt with decisively before it reaches uncontrollable levels.

Service delivery and borders

Development, or lack thereof, has been seen in many cases as one of the major reasons for people leaving their homes, is also connected to innumerable incidents of xenophobic attacks in several countries, notably in South Africa. On many occasions, the failure of the government to provide essential services and rising unemployment rates have led to violent public protests which have left migrants and refugees as scapegoats and victims of those protests.

Men and women of goodwill remind us that humanity is not dependent on nationality or one’s background

The importance attributed to borders and nationality over and above respect and protection of human dignity, has regrettably landed the international community in a situation of undesirable diminishing humanity. Men and women of goodwill remind us that humanity is not dependent on nationality or one’s background but, as David Hollenbach (2019) explains: “To act in accord with humanity is to act with inclusive concern toward all men and women, especially those who face persecution, oppression, or suffering. The borders separating people according to their ethnic, religious cultural or national differences do not set boundaries on the moral duty to respect human dignity.”

Pope St John XXIII (1963), using both religious and secular warrants, underscored that moral duty or obligation is not limited by national boundaries: “Every human being has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the confines of his own State. When there are just reasons in favour of it, he must be permitted to emigrate to other countries and take up residence there. The fact that he is a citizen of a particular State does not deprive him of membership in the human family, nor of citizenship in that universal society, the common, worldwide fellowship of men.” (Pacem in terris 25).

Despite all that and many more appeals for hospitality towards non-nationals, we have seen not only a rise in hostile attitudes towards non-nationals but xenophobic atrocities towards them as well.

It is crucial for host communities to be reminded that the persistence of hostilities and xenophobic reactions towards migrants and forcibly displaced persons is not only the protraction of human suffering but fundamentally the pervasive violation of intrinsic human dignity, the foundation of human rights.