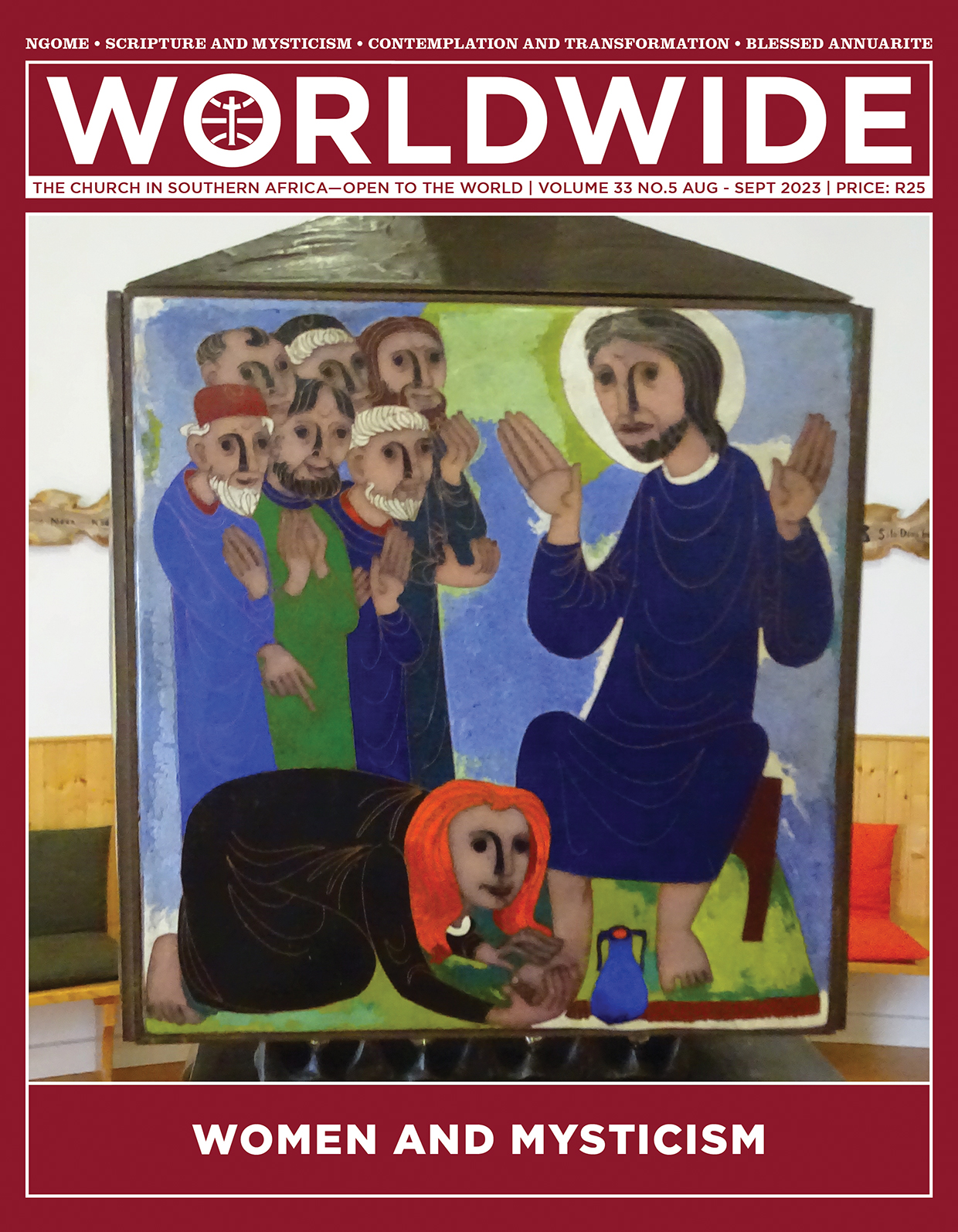

WOMEN AND MYSTICISM

Mary anoints Jesus’ feet at Bethany (John 12:1–8). The scene is part of a series which represents passages of women with a prominent role in the Scripture. The decorations are placed around the sides of the Tabernacle in the Chapel of Meditation at the University of Mystics in Avila, Spain.

Mary listens to and manifests her love for Jesus. Contemplation becomes the mesh in which her Spirit-led actions find their meaning and support.

SPECIAL REPORT • ELISABETH OF THE TRINITY

Scripture and Mysticism

What is ‘mysticism’ and how does it impact our understanding of Scripture? Is it possible that one’s spirituality can be enriched by a mystical approach? In this article, an attempt is made to answer this question, with reference to the biblical mysticism of Elisabeth of the Trinity

BY PROF CELIA KOURIE, PHD THEOLOGY | UNIVERSITY OF SOUT AFRICA (UNISA), PRETORIA

On Mysticism

Mysticism, unfortunately, has often been associated with abnormal phenomena, pathological states and religious sentimentality. However, the following definitions can shed greater clarity as to the meaning of mysticism: (i) Mysticism is a particular type of ‘awareness’; the doors of perception are thrown open, leading to a consciousness of union with the Divine, or the Ground of Being, or Ultimate Reality; (ii) It is a radical surrender to the loving embrace of self to the Other; (iii) It is an immediate contact with the Transcendent; (iv) For Christian mysticism, the consciousness of the divine presence, can be expressed as either oneness with God, unio, or fellowship with God, communio; (v) Mystical experience often exhibits a feeling of timelessness, bliss or serenity. This introvertive mysticism can be distinguished from extrovertive mysticism, for example, nature mysticism, in which nature is seen with unusual vividness and clarity, and a holistic rapport with the world is experienced.

Mysticism does not imply merely having an isolated experience which has no bearing on consequent life and behaviour. On the contrary, it is a manifestation of a deeper, permanent way of life, in which the purifying, illuminating and transforming power of God is experienced, effecting a transformation of the mystic’s entire being and consciousness. Mystics can be seen as paradigms of human authenticity; in many senses, they are pioneers, opening the windows to a life lived at greater depth, shedding light on what is often hidden, and pointing to a passionate encounter with Reality. They witness to the active infusion of Infinite Spirit into finite spirit, or perhaps more accurately, an awakening to the inner actualisation of the same.

Mysticism and Scripture

A mystical hermeneutic of scripture is one in which a direct experience of God, or Ultimate Reality, or the One is the end result. The difficulty of trying to express the inexpressible, to put into language that which is totally beyond language and even beyond thought, cannot be overestimated. Nevertheless, this does not deter mystics of all traditions from attempting to describe their experience and articulate its reality. In spite of the ineffability of the experience itself, mystics offer an array of texts in which the experience and its meaning are described. An interesting facet of a mystical reading of scripture is that whilst in certain cases, mysticism is clearly seen as an alternative to organised religion, there are, on the other hand, telling examples of mystical experiences

that resonate with the mystic’s religious tradition. In the latter case, there is a linkage of personal experience with revealed truth, in which what was known and described in the scriptures is experienced personally. A mystical reading of scripture witnesses to the life-giving power of the texts. The text breaks the spell of previously-held presuppositions, correcting and revising established views, and thus provoking a new self-understanding, effecting transmutation of character and daily life. The text is now more readily acknowledged as a mediation of meaning which takes place as an event in the reader and provides as it were a ‘door’ between different dimensions of consciousness. Often the journey into new dimensions necessitates entering into the silence, the void—the inexpressible. Word and silence are irrevocably intertwined. A clear example of scriptural mysticism is found in the life and writings of Elisabeth of the Trinity (1880-1906), in particular her insights into the teaching of Paul.

Elisabeth’s emphasis is on the illuminating function of scripture which confirms and explains experience

A Mystical Reading of Paul: the insights of Elisabeth of the Trinity

Elisabeth Catez was born into a French military family and after her father’s death in 1887, the family took up residence close to the monastery of the Discalced Carmelites in Dijon, where Elisabeth eventually began the life of an enclosed Carmelite in August 1901. Early in 1905, symptoms of Addison’s disease presented in her, and in the spring of 1906, Elisabeth was permanently installed in the convent infirmary, where she died on 9 November 1906, at the age of twenty-six. Elisabeth’s mysticism has been gleaned from what can be considered a few occasional writings and retreats. In addition, three hundred and forty-six letters by Elisabeth have been preserved. Elisabeth was canonised on 16 October 2016.

Credit: Willuconquer/commons. wikimedia.

How can Elisabeth contribute to a mystical reading of scripture? Her scriptural formation was almost non-existent. There is no evidence to suggest that any courses on scripture were offered to the Carmelites at that time, or that Elisabeth had access to commentaries on scripture. Elisabeth had access to the New Testament, but only to the book of Psalms from the Old Testament. Nevertheless, many references to the latter are to be found in her writings: these would have come from her spiritual reading and various retreat conferences. Nevertheless, Elisabeth is a scriptural mystic par excellence, and scripture provides the authority upon which her spiritual doctrine is built. Elisabeth’s emphasis is on the illuminating function of scripture which confirms and explains experience. Elisabeth, in accordance with her own Carmelite charism, was selective in her choice of scriptural teaching. Her choice of texts would have been influenced by the spiritual exegesis of her mystical mentors, inter alia, John of the Cross, Teresa of Avila and Jan van Ruusbroec. Elisabeth’s mystical reading of Paul, in particular, is a constant thread in her writings; as articulated in her mystical conformity to Christ.

Conformity to Christ

The centrality of Christ in the life and thought of Elisabeth is axiomatic from even a cursory survey of her writings. She was captivated by Paul, in particular, his teaching on conformity to Christ (Rom 8:29). As expressed in her poetry, Jesus is the ‘Splendour of the Father’ who incarnated in the individual, leads her to the intra-Trinitarian life of glory and praise. For Elisabeth, Jesus teaches what it means to know the Father in mystical simplicity and to live life in a divine way. It is noteworthy that Elisabeth had inscribed on the back of her crucifix at her religious profession, ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me’ (Gal 2:20b)—a clear indication of her desire to be transformed into the image of Christ. Jesus is firstly a model par excellence for her life as a Carmelite nun. Secondly, for Elisabeth, Jesus is not only a model and paradigm but also the exemplar and enabler, who shows what it means to be in the image and likeness of God. Jesus is the One who effects a radical transformation of the total person, a ‘Christification’, which leads to human authentication and divinisation.

novitiate, August 2, 1901. Credit: Willuconquer/commons. wikimedia.

The quintessential way in which Elisabeth interprets the tenets of scripture is by interiorisation, by assimilating and actualising them in her own life. The Christification process takes place within the depths of her being. Interiorisation forms a major principle by which Elisabeth interprets the historical events of Christianity and transmutes their meaning into a meta historical realm. For Elisabeth, the powerful Pauline expression ‘in Christ’ or ‘in Christ Jesus’ determined her life as a Christian and as a Carmelite. This formula is a synthesis of her entire doctrine, and transformation in Christ forms the bedrock of Elisabeth’s scriptural mysticism. This is effected in everyday living: a quotidian mysticism. It does not presuppose extraordinary states of consciousness, although there may well be ‘mystical touches’ at times, when the window of eternity is opened, and the fresh breeze of the Spirit allows a glimpse into Reality.

Elisabeth realised that the road of the cross is at the same time the way of beatitude

Redemptive suffering

True to the spirit of Carmel, Elisabeth saw suffering as the patrimony of her order, the salvific efficacy of which was seen to radiate beyond the confines of the cloister to help effect the redemption of humanity. Allusions to suffering pervade her mystical doctrine. With the progressive deterioration of her health, Elisabeth’s identification with the suffering Christ intensified. Owing to her scriptural understanding of the meaning of the cross, she bore her excruciating pain with deep patience and love. The secret of her strength is to be found in the fact that, in line with many mystics of her time and ours, Elisabeth realised that the road of the cross is at the same time the way of beatitude. For Elisabeth, therefore, it is not a question of mere reflection on the words of Paul, or speculation regarding the mystery of suffering. She teaches that pain and suffering can be transfigured; more exalted states of consciousness can exist contemporaneously with intense states of suffering. It is important to remember that Elisabeth would have been influenced by the passion mysticism that was a hallmark of late medieval piety and which continued to influence the religious consciousness of Western Christianity, particularly in France in Elisabeth’s time. A certain conditioning of consciousness regarding the desire for suffering would have been part of the milieu in which Elisabeth grew up. This approach is not emphasised to the same degree within contemporary spirituality, which is more holistic concerning health and wellness. However, for Elisabeth, identification with Christ crucified enabled her to find meaning in her suffering. As a result, suffering loses its enslaving power (Rom 8:35-39). Elisabeth’s acceptance of her own personal ‘crucifixion’ epitomises the summation of a life which consistently sought to be divested of self. Therefore, although Elisabeth did not read learned works of biblical exegesis, she discovered the transformative power of a mystical reading of scripture. Hers was not merely a passive reading, but a personal involvement with the text, allowing herself to be ‘described’ and ‘narrated’ by the words of the Bible, particularly the teaching of Paul. Elisabeth’s mystical lens, characterised by a freshness of approach, and a keen selectivity and perspicacity, illustrates the breadth and depth of the richness that is scripture. The illuminatory and existential significance of scripture is given due recognition. Thus, Elisabeth helps us return to our mystical roots, and rediscover our mystical heritage. This will open doors to a more translucent understanding of the ancient texts, an understanding of which will impact positively, not only in our own lives but also in society as a whole.