JOURNEYS OF LIFE

The painting on the front cover entitled “The disciples of Emmaus” reflects our journey of hope. Jesus not only walks with us, but gives us the wisdom to perform our ministries and opens our eyes to see Him in the people that we are serving.

YOUTH VOICES • MOBILITY

ONE STEP AT A TIME

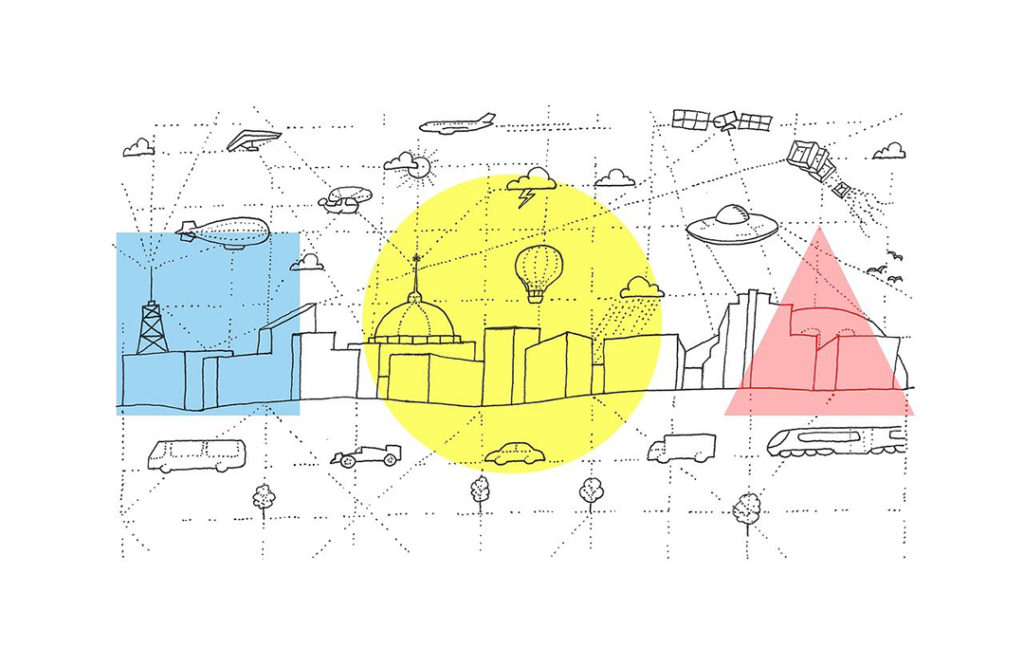

While the world’s population continues to grow rapidly, rising global warming is causing more frequent natural disasters and major havoc. The author of this article encourages the use and enjoyment of alternative eco-friendly and healthy ways of transport in our cities, instead of flooding our roads and highways with scores of individuals each making solitary use of his or her own car.

BY Jill Williams | Candidate Landscape Architect, Pretoria

FROM THE time we are born, we are constantly learning, growing and finding new ways of doing things. In terms of mobility, we progress from wiggling to crawling, from waddling to walking, from hopping to jumping and from jogging to running. Furthermore, we learn to ride, we are driven or flown. Mobility has no limitations—even if a person were to be stranded on an island, he or she would be able to create some form of water mobility in the form of for example a raft. Yet, the further we progress in terms of mobilising humanity, the more issues we face regarding sustainability. We have heard a great deal about the dire situation we face as a species on this planet. This means that everything we do going forward should be informed by environmental consciousness and action. We rely very heavily on the automotive industry to get from point A to point B. Understandably so, as this industry has radically changed the way we work and live, particularly since the Industrial Revolution. This transformation is, however, still a work in progress. The great leaps we have taken in technological advancement in the motor industry, for example, have not yet reached a level where this industry can develop a commercially viable, 100% environmentally friendly mobile mode of transport from production, to use, to decommissioning.

Sustainable and Eco-friendly mobility

The spaces and roadways allocated for vehicles are not always designed with the environment in mind. Often, large open spaces are allocated to parking lots—many devoid of green buffer areas or trees and shade structures. This results in large amounts of water escaping off these surfaces into storm water systems without being relayed back into the ground to recharge underground water supplies and sources. This means that we need to be responsible in the way we accommodate transport systems and the way we choose to be mobile. Though we cannot stop global warming by merely changing our attitudes towards transport and mobility, we can assist in the reduction of our impact on the environment by reconsidering how certain things are done.

When was the last time you walked to work or to the store, or went out for a leisurely stroll in your neighbourhood?

Using non-motorised transport or NMT means being mobile with what is perceived to be an environmentally friendly means of transport that does not necessarily involve an automobile. It entails the reduction of the impact of the transport system on the environment and on our health, in terms of pollution, the incidence of road accidents and on traffic regulation. In most cases, this is also the cheapest, most social, physically active and easily available means of transport. Examples include walking, cycling and using animal drawn carts/ carriages. While this may seem slightly out-dated and primitive, there is great merit in these traditional ways. Encouraging the use of NMT, in conjunction with a well-oiled public transport system, can be of significant benefit, particularly in developing countries, where obtaining one’s own vehicle may pose a real challenge. In countries like Bangladesh, the use of Tuk Tuks together with various forms of NMT such as cycling, walking and animal drawn carts are the order of the day. The use of Tuk Tuks is most fuel efficient; they even come in environmentally friendly electronic versions, with no fume emissions. In cities like Dakha for example, the lines between pedestrian walkways and roadways are very blurred due to population density. Therefore, multi-disciplinary approaches to mobility are required in order to ensure the safety of the population. NMT is however not applicable to developing countries only. The Netherlands, Japan and Germany are for example the highest ranking in terms of bike mode shares, as cycling and walking are very popular forms of NMT there.

When was the last time you walked to work or to the store, or went out for a leisurely stroll in your neighbourhood? What was it about that walk that made you think “I wish I did this more often”, or even “This was the worst thing I have done all day!”? The way streetscapes and open spaces are designed, greatly affects the way we experience even a simple walk through the neighbourhood. Factors such as lighting, upkeep and pathway and road widths affect one’s perception of safety and freedom in such spaces, which influences the walkability of streets and to what extent we enjoy spending time there.

Comfort seekers

Essentially, one has to evaluate one’s own lifestyle and needs to determine what the most sustainable and environmentally conscious way would be to live one’s own life. One example is the rise in popularity of E-hailing companies, such as Uber, Bolt and Taxify. Many people prefer this mode of transport to full-blown public transport, such as taxis, buses and trains, and they are therefore happy to pay a little extra, because of the availability, timeliness and ability of these services to pick you up and drop you off at any location, vs the scenario where you drive on a set route, as is the case with most public transport. Although this is a convenient way to get around, in terms of the environment this might not be sustainable when taking solo trips, as it is equivalent to driving one’s own vehicle to said destination. Shared rides and the use of public transport are less harmful to the environment, as less emissions are produced in transporting groups than individuals.

This brings us to the very heated internal debate on whether to use the stairs or take the elevator (or escalator) when needing to get to a higher or lower level in the mall or office building. Many of us choose the easiest, most convenient option that does not require much effort or the need for much exertion. This physical immobility, made possible by the availability and ease of technology which aids mobility, is crippling us in multiple ways. Immobility in this mobile world is more prevalent, particularly in urban areas, than one would think. The ability to order food, clothing, appliances, furniture and even educational materials online while remaining at home is both a blessing and a curse. COVID-19 showed us that it is possible to live and work from one place, without ever leaving one’s home or neighbourhood. Although this demonstrated how far we have come technologically, it also harboured a series of unhealthy behaviours. Many more young people prefer to “Netflix and chill” than to go out and be active. Having meetings online could mean long hours or even days of only seeing the inside of your house.

City designs

Sometimes, it is unfair to blame the mainly sedentary population. Looking at the way some streets are designed, it is very clear that the priority user is the person driving a motor vehicle. Often, sleek, heavily engineered roadways have little or no space for pedestrian use, forcing people to cross highways by dodging cars, or walking long distances to get to pedestrian bridges; particularly where squatter camps and townships have started creeping towards highways and road reserve areas, as seen in many parts of South Africa. There is little or no consideration for pedestrians in some cities as well, where no street lights, traffic lights or pedestrian crossings are in place to go through busy roads. According to the department of transport (2008), on a legislative and city-planning level, traffic calming measures such as speed bumps, traffic lights and traffic circles aid walkability and safety, as they reduce the speed of vehicles and thereby reduce the chances of pedestrian casualties.

Looking at the way some streets are designed, it is very clear that the priority user is the person driving a motor vehicle.

I have often experienced the necessity to travel using public transport or walking. Walking was the means used for shorter distances, such as in a 3km radius from home, with longer distances being covered by taxis and busses. I first started using the municipal bus regularly in 2021 and was pleasantly surprised at how efficient the system was. I would catch the bus at a stop near my home and be dropped off near work. This meant a mere 10-15 min walk was required to and from the bus stop. Cycling to and from work in the Pretoria CBD is possible, yet not necessarily the best option, as roads and walkways are not cycler friendly along my route. Neither is it safe to leave one’s bicycle in public areas.

Rational means of transport

In monetary terms, I would be paying half the money I spend on a car by taking a taxi, and I spend half of that taking a bus. I have not yet tried using the train (which would mean a 40-60 min walk to and from work), which is half to three quarters of the price of taking a bus. Although I have heard some negative stories about using the train, a colleague has indicated that it is quite acceptable. In considering the use of any transport mode, the amount of travellers should be taken into account, as driving a car full of people would cost the same or even less than having each person paying for a bus or taxi. Every now and then, protest action also occurs, which negatively affects busses and taxis in particular. This is why having multiple forms of mobility available to various income levels is a necessity in any society.

Finding a transport solution that is environmentally friendly, that promotes some form of physical activity and that suits ones’ own or family needs and preferences may involve some degree of trial and error. It is however possible. Each region probably has its unique and different solution that works best, but that does not prevent us from creating new ways of mobility. This is a necessity in order to prevent a world run by cars, resembling a ball of elastic bands, with highways stretching from one city or country to another, with little or no room left to simply take a walk.

References:

- Department of Transport. (2008). Draft National Non-motorised Transport Policy. Department of Transport. Republic of South Africa. pp. 38-39.