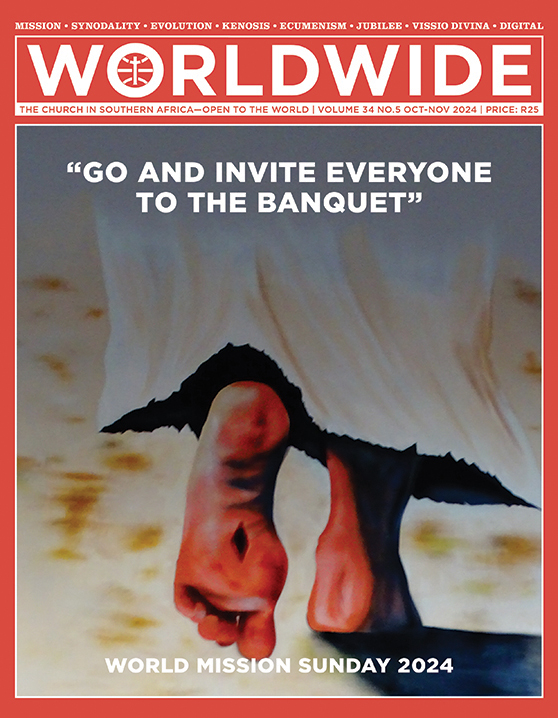

“GO AND INVITE EVERYONE TO THE BANQUET”

The image represents the feet of the Risen Jesus, in motion, showing the wounds of his Passion, yet ready to reach out and invite all to the banquet of his mercy. Likewise, Jesus invites to us to his mission in co-responsibility to bear witness to the power of his resurrection and to bring Jesus’ message of peace and fraternity to the whole world.

INSIGHTS • LIBERATION DIVIDEND

THIRTY YEARS – LONG ENOUGH?

BY MIKE POTHIER | PROGRAMME MANAGER, SACBC PARLIAMENTARY LIAISON OFFICE, CAPE TOWN

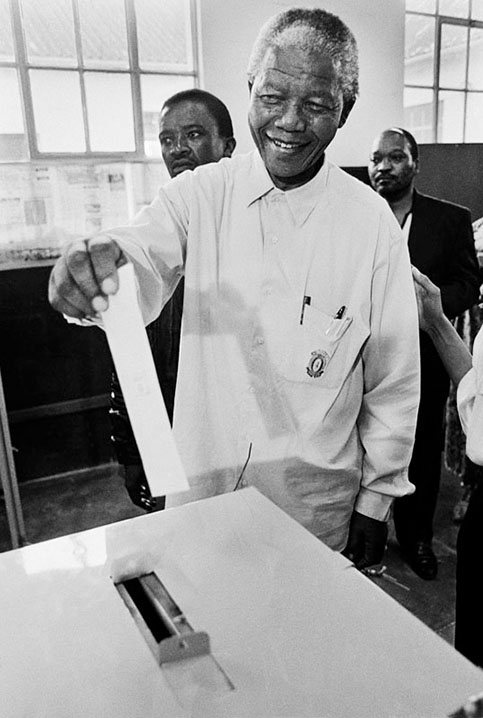

INTERESTINGLY, IN our recent national elections a majority of voters finally turned their backs, after 30 years, on the party that brought about their liberation—the party of Nelson Mandela and other heroes of the struggle, the ANC. Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it looked as if the ANC was in an immovable position, winning at one point 70% of the vote. This very strong showing was due, at least partly, to what is called ‘the liberation dividend’—the notion that the party of liberation enjoys a very high degree of loyalty and support from voters, even if its post-liberation performance fails to meet people’s expectations.

Thus, for a long time the ANC could get away with poor management of the economy, sustained high unemployment, and policies that, far from achieving true basic black economic empowerment, created instead a small layer of super-rich, often well-connected, individuals. It could also get away with an almost complete failure to address land reform issues, a continual decline in education standards, and an inability to provide the country’s youth with the skills that they, and the economy, need to prosper in the 21st century.

One could carry on listing such examples, though one could also, in fairness, list some genuine achievements—such as mass provision of access to electricity and clean water, and improved access to higher education for those who managed to make it through the school system. However, the point is that if it had come to power in one of the world’s old, established democracies, the ANC’s track record in governance would probably have seen it defeated electorally after at most ten or 15 years. It was the liberation dividend that kept ANC in office with a clear majority for so long.

But no more. After 30 years the voters, it seems, had enough. Thirty years is a significant period. It means that none of the voters between the ages of 18 and about 40 have any personal memory of the time of liberation, let alone of the apartheid era that preceded it. In our country, that age cohort makes up approximately 12 million of the 28 million registered voters, or 43%. For these voters, what happened three decades ago is obviously less important than it may be for their parents and grandparents; for them the disappointments of today outweigh the triumphs of yesterday.

Voters are sending a message that they will not put up with poor governance, corruption and arrogance from their leaders indefinitely.

In the early 1990s, roughly 30 years after the great wave of African independence in the 1960s, people in Zambia, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and some other African states also turned against their own parties of liberation. Admittedly, in most of these countries there had been one-party systems, rather than true democracies. Should voters have had the opportunity to choose other parties in free and fair elections, we do not know if they would have done it within the 30-year span. The fact is that the demand for multi-party democracy and free elections in these countries was led by younger people, for whom the great heroes of the 1950s and 60s, Kaunda, Kenyatta, Nyerere, etc., meant comparatively little.

In some other countries, liberation movements and dominant parties have managed to cling to power for much longer than 30 years, Zimbabwe being perhaps the prime example in Southern Africa. To do so, they have had to rely on the subversion of democratic practices—rigging elections, imprisoning opposition leaders, clamping down on independent media voices, and so on. Further to the north, similar processes are underway in countries like Rwanda and South Sudan.

Ultimately, the end of the liberation dividend is a sign of accountability—voters are sending a message that they will not put up with poor governance, corruption, and arrogance from their leaders indefinitely. This is something that is perfectly normal in established multi-party systems, where governing parties are regularly held to account for their faults—as has just been seen, for example, in the United Kingdom. It is a new experience in South Africa only because of the liberation dividend. Let us hope that, now that the electorate has done it once, it will realise that this is how democracies are supposed to work. The next opportunity is around the corner—the municipal elections in 2026 will take place 30 years after we first voted for our town and city councils back in 1996.