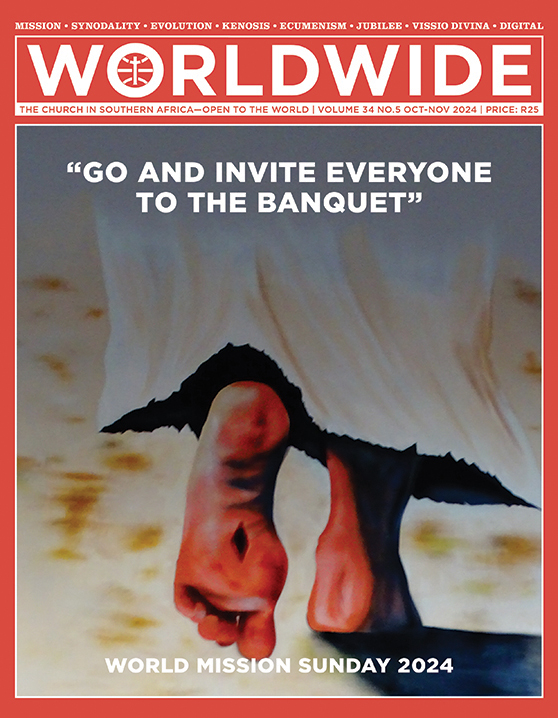

“GO AND INVITE EVERYONE TO THE BANQUET”

The image represents the feet of the Risen Jesus, in motion, showing the wounds of his Passion, yet ready to reach out and invite all to the banquet of his mercy. Likewise, Jesus invites to us to his mission in co-responsibility to bear witness to the power of his resurrection and to bring Jesus’ message of peace and fraternity to the whole world.

PROFILE • JACQUELINE HUGGINS

BRINGING HOME SCRIPTURE

To enable congregations of any missionary endeavour to read and hear the Word of God in their own tongue is absolutely essential. Jacqueline Huggins became the first African American woman to translate the New Testament. She chose as her beneficiaries a minority group, the Kagayanen people of the Philippines.

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

VERY NEAR where I live in the Diocese of Argyll and the Isles in the west of Scotland sits Carnasserie Castle, an ancient ruin with an interesting history. It was there that The Book of Common Order—a book of prayers by John Knox of the Reformed Church—was translated into Scottish Gaelic by Séon Carsuel (John Carswell in English), Bishop of the Isles, and printed in 1567. This is considered the first printed book in Scottish Gaelic. It wasn’t until 1767 that a Gaelic translation of the New Testament was printed, and in 1801, a full translation including both the Old and New Testaments was published.

I won’t go into the details of that very complicated period of Scottish history, but my research into the social history of Argyll and the Isles confirms for me the importance of taking the Word of God to people in their own language.

Disseminating the Word in local languages is surely vital to the core of missionary work.

My connections with Africa bear out that theory. Disseminating the Word in local languages is surely vital to the core of missionary work. The language we speak from infancy shapes how we understand the world—and that emphasises the importance of translating the Bible into languages spoken by minorities. Although indigenous peoples now account for just 6.2% of the world’s population, they speak over 70% of the world’s languages. Those languages are key to indigenous cultures, philosophies and traditional knowledge, and if we are to share knowledge and beliefs, we must respect them, learn them and translate into them.

Faith in one’s own language

This is why people like Jacqueline Huggins play such an important role in today’s concept of “mission.”

According to Faith News Network, 6,912 languages are spoken in the world today, and of these, the Bible is only fully translated into 426. Jacqueline Huggins spent more than 20 years translating the New Testament into the Kagayanen language, which is spoken in the Philippines by just 25,000 people. It was published in 2008, to much acclaim by Wycliffe, the specialists in Bible translation.

The publicity was as much because Huggins was the world’s first African American female to ever complete a New Testament translation as to the fact that this ethnic minority now had access to the New Testament in their own language. Huggins was keen to emphasise that this had been teamwork—and that it might never have happened at all if she had listened to one warning. She said at the time of publication, “I knew God was calling me to Scripture translation. Incredibly, one church leader attempted to discourage me from pursuing that call, saying, ‘You won’t be accepted by Wycliffe because you are black. And you are a female.’”

Teamwork

She added, “It became clear that divine intervention brought this diverse team together—with our distinct gifts and abilities—to complete the translation project and serve those who speak the Kagayanen language.” It’s clear that her stress was on the importance of the translation to that minority population.

It’s clear that her stress was on the importance of the translation to that minority population.

The team included three translators and three support staff, comprising Americans, Malaysian Chinese and Singaporean Chinese. Huggins spoke at length at the 1997 Missions Conference about the complexities of such a translation. It had, after all, taken her a couple of decades to complete the task.

What led her on the path to the Philippines? She had, she admitted herself, been decidedly anti-religion in her early life—a life that had not been easy.

Journey towards God

She was born in Philadelphia in the US on October 22, 1949, to Fenton and Doris Wilson. There were two siblings: an older brother, Mark, and a younger sister, Janice. Jacqueline was fostered out to two different families by the age of nine. She got married later, had two children, and in her late 20s became a fortune teller. Her early life was one of poverty and abuse, and it was little wonder that she very consciously rejected any kind of faith involvement.

She actively discouraged others from their faith, and according to Wycliffe Bible Translators (2017), “When a chance came up to go to a Bible study, she saw it as an entire audience of misguided Christians that she could set straight.”

But this plan was not to be. Her pet cat died on the evening of the Bible study event, which made Huggins question her philosophy. A voice told her to look for the Bible a relative had given her. It took some finding, but when she did, that “voice” suggested she look up the word “repentance.” That led her to Romans 2:4, where she read about God’s tolerance and kindness. It was then that she wondered, “Wouldn’t it be something if there really was a God, and I’m the one that’s wrong?”

This encounter with the Holy Spirit—she described it as such—occurred in 1977. It was life-changing. Instead of trying to persuade others to turn away from God, she decided to try talking to Him. Before long, she found herself studying at Bible college.

Bible studies

Her first stop was Fort Wayne Bible College in Indiana, which later became Taylor University. She majored in missions and Biblical languages, learning both Greek and Hebrew. There were short missions, including a spell with Haitian migrant farm workers in 1981, and then in 1982 she joined Teen Missions International, co-leading 30 students to build a church in the Philippines. Little did she know that in a short while, the Philippines would become a permanent base for her life’s greatest task.

She had become aware of Wycliffe Bible Translators—the organisation she was warned wouldn’t entertain her because she was Black AND a woman—while she was at college. Her qualifications made her an ideal candidate to train with them at the International Linguistics Centre in Dallas, Texas. In 1984 she became a member of the Wycliffe Bible Translators and in 1986 she returned to the Philippines and began her life’s work in earnest in Cagayancillo in the province of Palawan, which today has a population of 6,884 people. This work involved being a language consultant and Bible translator, and the translation of the New Testament into Kagayanen would eventually take two decades.

Translation: A spiritual work

At a Missions Conference in 1997, she spoke to delegates about the process of translating the Bible. It is not, she told them, just about having a grasp of languages:

“Number one prerequisite for a Bible translator is that you have a knowledge of the author of the Scriptures. That you know God. This is a spiritual work. Yes, it’s a technical work, but it’s also a spiritual work. And unless you have a personal relationship with God and the Holy Scriptures, you’re just doing a mechanical thing, and the Holy Spirit is not involved. And I can tell you there are times in the translation process that you have to totally rely on God for answers, on how to say something in that language that you’re translating into. And you may have a lot of linguistic background, a lot of linguistic training, but sometimes it is the Holy Spirit that will give you an answer to a difficult problem. And if you don’t know Him, you’re really going to be stuck.”

In two decades, she had transformed from the woman determined to prove to believers that there was no God, into the woman persuading a packed conference hall that however much linguistic training they had under their belts, they would get nowhere without God’s guidance.

Of course, she emphasised the need for high-grade language qualifications, but the essence of what she told those delegates can be found in Pope Francis’s Fratelli Tutti encyclical, and she saw that ethos as being of overriding importance.

Translation: A spiritual work

She said: “You have to have preparation in non-western living. You have to actually divorce yourself from your cultural grid in the way you are used to seeing things and begin to look at things in another way. The people that you minister to, they’re not backward. They’re not primitive. I still hear words like that today. We are going to people who do things differently.”

Huggins is suggesting that we are all brothers and sisters, as Pope Francis’s document says:

“The world exists for everyone, because all of us were born with the same dignity. Differences of colour, religion, talent, place of birth or residence, and so many others, cannot be used to justify the privileges of some over the rights of all. As a community, we have an obligation to ensure that every person lives with dignity and has sufficient opportunities for his or her integral development.”

Huggins stressed to that 1997 audience of would-be translators that they wouldn’t be embarking into a translation job as soon as they arrived in the area they had been sent to. They were going to get to know their brothers and sisters by learning their language from the bottom up.

She said: “You’re going to study that national language and culture first. It could be Swahili if it’s an African nation, or Tagalog if it’s in the Philippines or Pidgin or Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea or whatever the national language is. You’ll learn that first for a few months just so you can get around, go shopping, and survive.”

And she told them to do what she had clearly done: make friends with local people, be part of the community, learn how things are said and the different ideas used to express feelings and actions.

The translator must get into the very bones of the people speaking that language.

Sackcloth and ashes may well not hold any significance for the people of Papua New Guinea, and Huggins knew that to make sense of the New Testament’s 8,000 verses, the translator must get into the very bones of the people speaking that language.

She would go on to become a Language, Education and Development consultant, assisting translation teams to compile dictionaries, having gained a PhD in Linguistic Anthropology from the University of the Philippines in May 2016.

The young woman who had to turn her home upside down to find a Bible, learned over time that to translate the New Testament in a way that would be completely meaningful in Kagayanen, her team had to make sense of words like repentance, sanctification and salvation.

She did it. She achieved this new trend of mission.