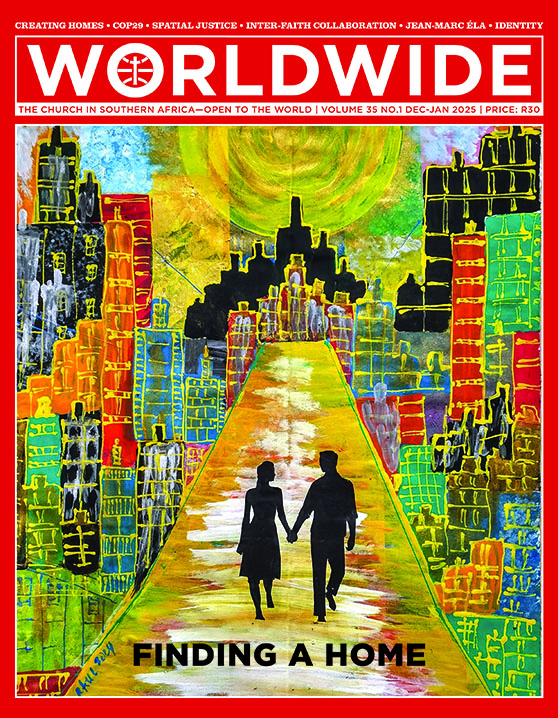

FINDING A HOME

This painting represents the reality of so many people in the world looking for a place to stay, especially as they flock into crowded modern cities, searching for jobs or fleeing from various situations of conflict. The need to create living spaces for them is acute. Like Joseph and Mary, who found no place at the inn, millions of people risk ending up unsheltered in the streets and deprived of a dignified dwelling which they can call home.

Painting by Fr Raul Tabaranza MCCJ

SPECIAL REPORT • SOCIO-SPATIAL JUSTICE

HOUSING: A VERB AND A PLACE

The word ‘housing’ does not just refer to a place, but it is also a verb. It is an active process of homemaking, of mediating access to the city, of ensuring that all people, regardless of vulnerability, income levels or special needs, have a place to stay. ‘Creating home’ is an on-going task, which will only come to its conclusion once nobody is unhoused or homeless.

BY STEPHAN DE BEER | DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRE FOR FAITH AND COMMUNITY, AND PROFESSOR OF PRACTICAL THEOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA*

HOUSING IS an expression of socio-spatial justice. Without access to a basic, tenure secured, affordable and well-located space, it is virtually impossible to make provision for schooling, healthcare, employment or emotional well-being.

In South African cities, and those in the developing world and the global south in general, housing is a commodity for the wealthy; millions live on the outskirts of cities, perpetually vulnerable and struggling to make ends meet.

A just city will be one that secures housing for its poorest and most vulnerable inhabitants. Anything less makes it to be inequitable and unjust, often for large percentages of its population. Even well-branded attempts at housing and neighbourhood improvements—if persistently on the urban margins and disconnected from urban opportunities—should be critiqued and dismantled for the perpetuation of the unjust city.

Self-help housing

Where the state and conventional housing developers fail to produce housing that works for the urban poor, the poor create their own housing solutions. Informal settlements are made up of self-help housing, where people incrementally develop their land, once they are able to secure legal rights to their space. Sometimes, vacant or abandoned properties are occupied by unhoused or precariously housed people, as survivalist or activist political strategies, to claim a right to the city and urban housing, making visible the precarious exclusions of unhoused populations.

The tip of the iceberg

Homelessness is the ultimate form of a housing challenge, causing millions across the globe to live unhoused, ‘under the sky’, under bridges, in cardboard boxes, or in temporary spaces from where they can be evicted at any moment. Homeless families are particularly vulnerable in every imaginable way. Some people may opt for homelessness, to escape abusive family situations, to be in proximity to possible employment, or to access desperate medical care. Innovative housing solutions need to be crafted in partnership with unhoused people, contextually responsive to their pathways into homelessness.

Theological and pastoral issue

The incarnation of God stands in deep solidarity with millions of unhoused people and migrant refugees. Jesus and his parents could find no place to lay their heads, and soon after birth, they had to become refugee migrants in Egypt. ‘There is no room in the inn’, should be heard as the universal cry of millions of people displaced across the globe. The Christmas story should reconnect us to the God who became human in the form of an unhoused migrant.

The Church that is not practicing the solidarity and humanity of its founder, is a Church alien to Jesus. He was a stranger and unhoused, but the Church has failed to embrace him repeatedly. Through our preaching, liturgies, pastoral care and social concern, we should shine a light on the inhumanity and indignity of the world’s unhoused or precariously housed populations. We should lament the Rafah in Gaza, and in our own backyards. We should work relentlessly to prevent and overcome the housing crises which all our cities face, even in the global north. We should reclaim a right to the city, for all its inhabitants, including those who are internally displaced as well as those who have fled from across our borders.

‘A fit for everyone’

Yeast City Housing (YCH) has, since its creation by the Tshwane Leadership Foundation, addressed the challenges of low-income and vulnerable inner-city populations. It has pursued a “yeast” effect in the city, forming new households from the grassroots, rising amidst exclusion, and welcoming anyone who has never been welcomed anywhere else. Over the years, YCH has developed 1 400 units to accommodate more than 4 000 people per night. Its housing includes differently sized apartments for low-income families, single rooms and forms of communal housing. In addition, YCH has recognized the special housing needs of some particular groups—older persons who rely solely on social grants; people who have become physically frail with nowhere to turn to; those with chronic mental illnesses; women or children, victims of violence or abuse; and homeless persons in general, who are trying to find a foothold for themselves in the city.

In addition to rental housing options in apartments or communal housing, YCH has created supportive housing for the above-mentioned groups; palliative care for terminally ill people; and transitional housing for those who are recovering from trauma or are re-establishing themselves in jobs.

Housing solutions can never be ‘one size fits all solutions’, as people have very specific and diverse needs, family sizes, and aspirations. We need therefore to acknowledge and offer diverse housing solutions. Other groups falling through the housing cracks now are LGBTIQ+ individuals who experience homelessness and stigmatization from shelters; chronic substance abusers who are not yet rehabilitated; and refugees and migrants from across our borders. The verb “housing” needs to be practiced; the harvest is plentiful.

Obstacles to innovation

To house the city’s most vulnerable populations requires innovative uses of space and resources, supported by enabling policies and understanding government officials. Sadly, from an initial situation when innovation in housing was rewarded, those tasked with leading government initiatives have regressed to cookie-cutter approaches that advocate ‘one size fits all’ housing projects, often leaving large numbers of people out in the cold.

Among the obstacles are the cost of land and the unavailability of property for innovative, affordable and just housing solutions. The fact that housing requires a complex set of technical, managerial, and social skills, which often come at a price, does not make it easier.

Creating our own tables

It is high time that the Church as collective rises to the occasion. In the South African context, the Church is one of the largest landowners, yet often does not account adequately for the property it owns, nor stewards it in ways that address the deepest needs of our people.

Our Church land and properties can become multi-purpose facilities which include various housing forms. We can use our air space to build high rises that offer a range of housing options, from penthouse apartments at market-related prices, to social housing and housing for those with special needs. Experience has shown and proved that the assumption that people in various income situations cannot share spaces, is false and has been refuted in many situations through well-managed and innovative housing solutions.

The Pauluskerk in Rotterdam is but one example of a Church accommodating both wealthy people, others in social housing, unhoused people, and undocumented and asylum-seeking individuals. The arms of the Church should be as wide and embracing as the arms of God in the way in which it constructs its vision and creates its own tables of resource and possibility, to sustain innovative and sustainable housing forms.

Many people with the necessary technical, managerial and social skills needed to make housing work, are sitting in our pews and generating their salaries from the skills they have. What about summoning their talents and gifts as a broader vocation, serving unhoused populations and those precariously housed, as we journey towards a new land? Could we center the cry for housing as part of our church’s mission agenda? What if we could indeed meet Jesus in the stranger, the unhoused, and those on the fringes of the city, trying desperately to make ends meet, on land not yet their own?

God’s shelter

Instead of promising only spiritual shelter to those who are unhoused, whilst we are sure where we will be sleeping tonight, we should perhaps read Psalm 91 together with the unhoused populations, in a new and material way: ‘to find shelter and rest in the shadow of the Almighty’; ‘to find refuge and a fortress in God in whom we trust’; ‘to be saved from the snares of the street and the unhealthy state of being homeless’; ‘to be covered under the wings of God’s faithfulness’; ‘to find a safe dwelling because God loves me’; ‘to be protected from trouble, because God saves me’. The salvation-liberation of God starts with Jesus becoming human, without a place to lay his head, a stranger in a foreign land. Such is the salvation-liberation message Christ wants to announce: for all those who are unhoused or precarious, under God’s wings they might find protection —spiritually, emotionally and physically— not only in the household of faith, but in homes that are safe, affordable and tenure secured, because God loves us.

*Stephan de Beer is passionate about sustainable alternatives to homelessness, and the potential role of faith communities in mediating sustainable housing solutions for and with the urban poor. Stephan.debeer@up.ac.za