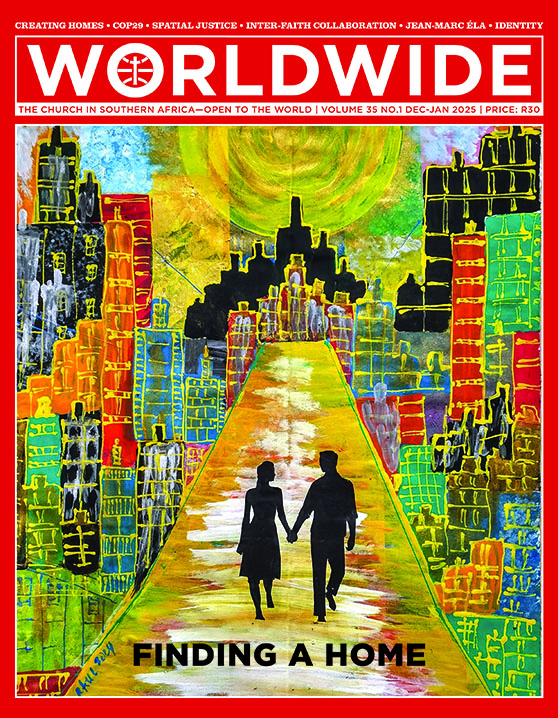

FINDING A HOME

This painting represents the reality of so many people in the world looking for a place to stay, especially as they flock into crowded modern cities, searching for jobs or fleeing from various situations of conflict. The need to create living spaces for them is acute. Like Joseph and Mary, who found no place at the inn, millions of people risk ending up unsheltered in the streets and deprived of a dignified dwelling which they can call home.

Painting by Fr Raul Tabaranza MCCJ

SPECIAL REPORT • BRINGING PEOPLE TOGETHER

CATHOLICS WORKING WITH ALL FAITHS TO SERVE THE HOMELESS IN DURBAN

There are many examples of Catholic parishes around the world which help the homeless. Some run soup kitchens or hand out sandwiches; make their halls available for people to sleepnin during winter or collect and distribute second-hand clothes; some are even involved in running training programmes or in helping unsheltered people find work and become self-sufficient. However, the Denis Hurley Centre in Durban adds an extra dimension to this ministry.

BY

DR RAYMOND PERRIER

| DIRECTOR OF THE DENIS HURLEY CENTRE, DURBAN

PHOTOS BY DENIS HURLEY CENTRE

PERHAPS OF all social issues, homelessness is the one that is a very natural fit for Catholics. We often have big facilities available in inner-city areas (which were once prosperous and are now run down); we have the inspiration of saints who have sided with the homeless (the Franciscans, the Jesuits and the Sisters of Mercy were all founded by people who left rich households to live on the streets); and we have the words of Matthew 25 ringing in our ears: “I was hungry and you fed me, naked and you clothed me…”. When Pope Francis was elected and declared that he wanted us to be ‘the Church of the poor’, few Catholics found that surprising.

A homeless called Jesus

Many years ago, as a Jesuit novice, I was helping in a very poor parish in central Glasgow and we had an old, bearded, homeless man who would come in and spend his days taking refuge in the church—Hollywood could not have created a more stereotypical scene. The parish priest would say to me ‘Has Jesus come in today?’ or ‘Have you given Jesus a cup of coffee?’ So, I asked him why, when talking about someone other people would call a tramp or a vagrant or a para, he called him Jesus. “I call him Jesus,” the priest replied, “just in case he is.” Matthew 25 in action!

At this time of year, we are especially conscious of the plight of the homeless because of the image of the Holy Family. Although Christmas cards, nativity scenes and traditional carols have tried to sanitise the scene, we remember that the family of the new-born Messiah found themselves homeless when they turned up in Bethlehem: sleeping with the animals was less about tinsel and fairy lights and more about the smell and noise and filth that a houseless person often has to face when planning to ‘lay down his sweet head’.

At the Denis Hurley Centre (DHC) in Durban, accompanying unsheltered people throughout the year is the lifeblood of what we do. We serve meals (170 000 this year), we provide primary healthcare (seeing 2 000 homeless and refugee patients each month) and we assist with family reunification, drug rehabilitation, training and job-seeking.

Inter-faith ministry

Many churches have inspired similar programmes, some larger and some smaller than ours. What is unusual about the DHC is that, although named after the man who was the key figure among Catholic Bishops in Southern Africa for almost 60 years, ours is a place where Christians of all denominations and people of all faiths come together to serve the unsheltered.

In April 2020, reporting on Durban’s response to protecting houseless people during the COVID lockdown, the following comment appeared in several newspaper stories:

“A Christian NGO serves breakfast for 1 500 homeless people, a Hindu corporate provides lunch, Muslim community groups deliver supper—and the Jewish club provides refreshments for all the workers.”

Durban in fact has a well-founded reputation for interfaith collaboration—not only the churches, mosques and temples but also NGOs, corporates and community groups.

The DHC is right next door to Emmanuel Cathedral, but on the other side of the DHC is the historic Grey Street Mosque. The sound of the muezzin calling the faithful to prayer mixes with hymns coming from the Cathedral.

This inter-faith collaboration expresses something that has been true of the city since its founding. Durban is not a Christian city that the Muslims arrived at, but rather a place where all religious groups arrived within a few decades of each other and which they thus created side by side.

We each draw sustenance from our different roots but, by working together, our branches are broad and strong.

Funding for the DHC comes from all the faith communities and all segments of the Christian community. How can one explain this interfaith and ecumenical collaboration? It would be great to be able to say that this is a defining feature of people of faith: an extension of Tertullian’s famous remark: ‘See how these Christians love one another!’ All faith traditions motivate their followers to do good works for the poor. But they usually see these good deeds as having to be done separately, not in partnership. In fact, whilst the Qur’an discourages rivalry between people of faith, it encourages competition when it comes to charity: ‘Compete with one another in good works’ (Quran 5.48).

Collaboration

Our own Catholic faith tradition has a good record of serving people of all faiths, but a bad record of collaborating with people of all faiths. The 1989 vision statement for the Catholic Church in South Africa was ‘Community Serving Humanity’. The openness of ‘serving Humanity’ is rightly applauded—but what is not remarked on is the emphasis that it is a particular [Catholic] Community doing the serving.

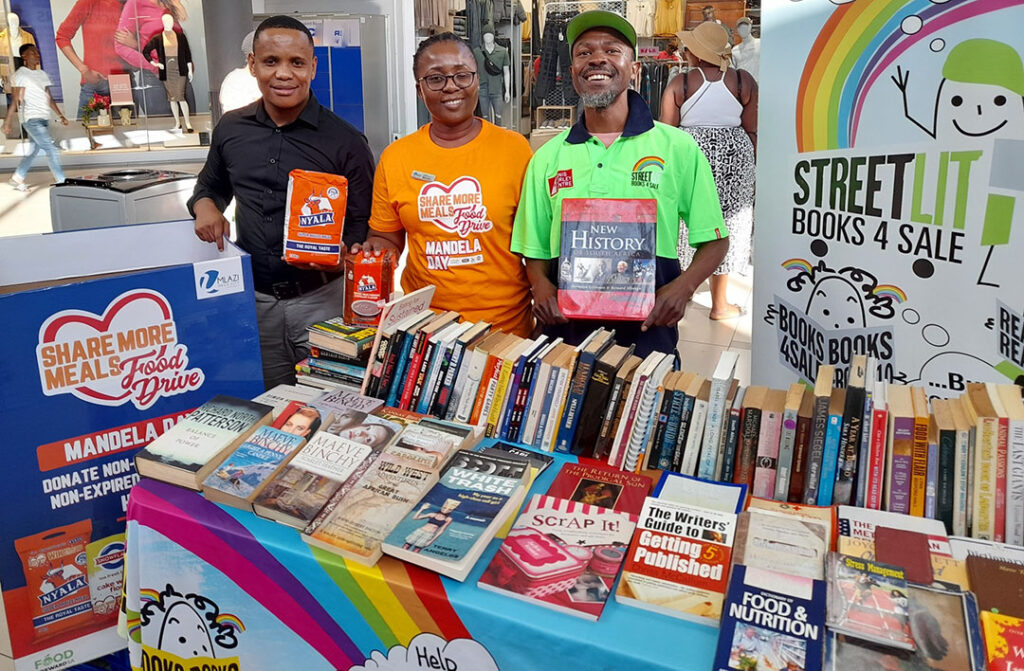

The one project that has worked is called Street Lit, in which houseless people become self-employed booksellers.

In Durban, it is different. The presupposition is that, however, much one community might be able to achieve, it can do much more when it works with other communities to serve humanity. This is due to the fact that no one faith dominates the history of the city, but it is also part of a general culture of collaboration in Durban. Prayers at meetings of the Durban Homeless Network draw on a wide range of traditions but seem to be able to inspire everyone. We each draw sustenance from our different roots but, by working together, our branches are broad and strong.

We need to respond to the immediate need of feeding people, but it is also vitally important how we feed them. We have a simple rule: we only serve food that we would be happy to eat ourselves; to show respect for the Muslim homeless who come to our door, ours is a halaal kitchen—as far as we know the only one in the world in a building named after a Catholic Archbishop!

Self-employment

The Human Sciences Research Council conducted a comprehensive survey in 2016 about homelessness in Durban. It substantiated what is very clear from a drive through the city—that the vast majority of houseless are young South African men (of all colours) who came to the city looking for work, did not find it and ended up on the streets. So, it is important that we help homeless people become financially self-sufficient. To be fair, we have tried and failed with a host of projects: eco car washing, casual manual labour, newspaper selling.

The one project that has worked is called Street Lit, in which houseless people become self-employed booksellers. Churches, mosques and temples promote and facilitate the collecting of books (usually in middle-class suburbs); volunteers help sort and store the books, and also train homeless people to take over this task; the entrepreneurs then cultivate trust between themselves and selling venues (art events, schools, shopping malls and churches) and trade the books to make money! This also shifts perceptions because now, instead of looking down on homeless people (who are shining our shoes or cleaning our streets), we look them in the eye as people who enjoy the same books we do.

Intermingling

Another example of a positive interaction is that from the outset, our kitchen has been staffed with homeless volunteers who work alongside the housed to prepare meals. Thus, homeless people are given a chance to be more than just recipients— not victims, but agents in their own welfare. The fact that regular volunteers serve alongside the unsheltered has an element of advocacy in it. Our centre is not situated in an area which middle-class people come to very often, but we have acted as a bridgehead that gets them back into the city centre. In this way, we are challenging perceptions of the city. Once they realise that they are working alongside the very people they came to serve, their perceptions of homeless people are challenged.

I recall an older, middle-class white woman who had been volunteering to feed homeless people and who confessed to me that she had initially been anxious because she was nervous of ‘the homeless at the traffic lights’. ‘But’ I asked her, ‘are you nervous of Vusi? (a young man from the streets who had been working alongside her that morning). ‘Of course, not’, she immediately replied. ‘I don’t see him as homeless; I see him as Vusi’.

So, we encourage groups from companies, private schools and government departments to come in and volunteer—not only for their willing hands but to help open their minds.

Advocacy

We also need to change the minds of those running eThekwini Municipality; their attitudes and policies towards the houseless have been dismal. At best, they have completely ignored them. But sometimes they have also introduced policies that unintentionally disadvantaged the homeless (such as closing 24-hour toilets). And at worst, they have funded especially harmful activities—such as night-time raids to pick up people off the streets and dump them outside the city.

Each year the atmosphere becomes more relaxed, and ‘reconciliation’ does not become a big theological act but a small human gesture of a shared conversation, a song or a dance.

In the face of this, we have pursued a relentless strategy of drawing media attention to these human rights violations with television exposés, features in newspapers and by constantly making sure that these stories are told. As St Oscar Romero would put it—our role is to be ‘a voice for the voiceless’.

Meal of Reconciliation

There is one annual event which is, in many ways, a culmination of our vision as an organisation. In South Africa, 16 December is a public holiday that, since 1994, has been promoted as a unifying event: a Day of Reconciliation. Most faiths have at their core a meal as a symbolic act of reconciliation—the Christian Eucharist, the Jewish Passover, the Muslim Ifthaar during Ramadan. By definition, these meals are all reserved for people within each religious tradition. None of them considers the heavenly vision of a meal in which all the righteous join together in one communal gathering. So, for the Day of Reconciliation, we have established an annual Meal of Reconciliation. This is not a meal in which the rich serve the poor, but a meal at which the rich and the poor are served together, sharing the same meal at the same table.

We are not in heaven yet, so it is far from perfect. Housed people like to run around and help—partly to be useful, but also to avoid talking to others. Homeless people, so used to ‘eating and running’, need to be encouraged to stay for a dinner party. Differences of faith are usually not a problem but, being South Africa, differences of colour are an issue, at least initially. But each year the atmosphere becomes more relaxed, and ‘reconciliation’ does not become a big theological act but a small human gesture of a shared conversation, a song or a dance.

We are not disguising the differences that exist between people but, we hope, providing a context in which those differences do not get in the way of people discovering what they have in common.

We are each nourished by our own faith roots—but the tree that we all inhabit has wide branches, big enough to accommodate even those who thought they had no place to call home. ‘The Lord of hosts will prepare a lavish banquet for all peoples on this mountain’ (Is 25:6).