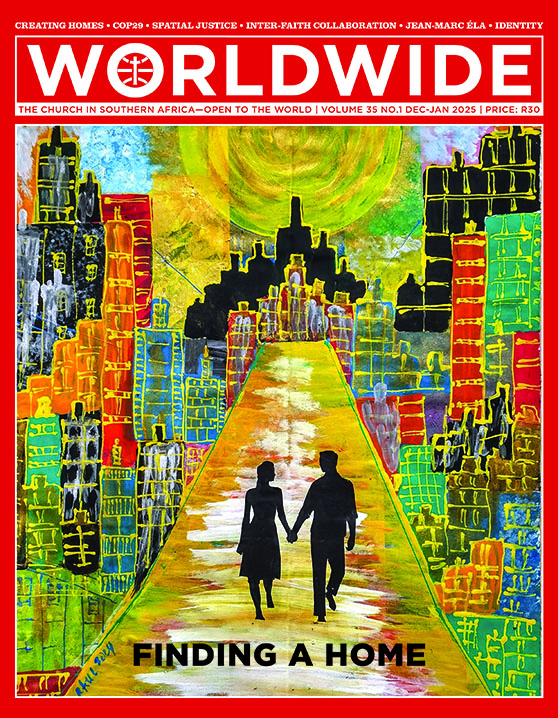

FINDING A HOME

This painting represents the reality of so many people in the world looking for a place to stay, especially as they flock into crowded modern cities, searching for jobs or fleeing from various situations of conflict. The need to create living spaces for them is acute. Like Joseph and Mary, who found no place at the inn, millions of people risk ending up unsheltered in the streets and deprived of a dignified dwelling which they can call home.

Painting by Fr Raul Tabaranza MCCJ

SPECIAL REPORT • TLF

CREATING HOMES IN TSHWANE

The Tshwane Leadership Foundation (TLF), a faith based Non-Profitable Company, seeks to create Pathways out of Homelessness for the most vulnerable communities in Tshwane (Pretoria). The author explores what churches could do to foster a ‘home’ environment in our democratic society.

BY LANCE THOMAS | CENTRE FOR FAITH AND COMMUNITY, PROJECT MANAGER, PRETORIA

WHEN PRESIDENT Cyril Ramaphosa announced the COVID-19 national lockdown in South Africa (Kiewit, Lester et al. 2020), people in the homeless sector where frantically wondering what would happen to those unsheltered. Being prohibited to be in the streets without a permit, would technically make homeless persons “illegal”. Fortunately, the President announced that a provision would be made for the homeless. In Tshwane, 2 000 homeless people were initially “dumped” in the Caledonian Stadium with limited access to running water and scarce PPEs. The total lack of social distancing placed these people at extreme risk. Providentially, a solution involving government and civil society was then found; within two weeks, every homeless person was housed in one of the 20 spaces found across the capital: in church spaces, town halls, unutilised offices, backyards and other vacant spaces. Special services were offered to the homeless communities by care workers.

The Inn

The TLF, together with Yeast City Housing (YCH), another faith-based social housing company, created 30 shared units available for old homeless people— those who could neither work nor afford accommodation on a state pension— at Hofmeyer House, a property owned by the YCH. The project was named The Inn, in remembrance of Joseph and Mary, who could not find accommodation at the Inn, in Bethlehem.

This project worked well until the YCH and the TLF started to experience financial constraints. Hofmeyer House may now need to be sold to a private property developer, putting the shelter of the dwellers of The Inn at risk.

Some background

The Tshwane Leadership Foundation was initiated on 18 January 1993 and was located in two old houses on Burgers Park Lane, Pretoria Central. Known then as Pretoria Community Ministries, it was started by a few individuals, with the support of six inner city churches: the Roman Catholic Church, the Anglican Church, the Methodist Church, the Dutch Reformed Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Congregational Church. They created a trust to fund this truly ecumenical project.

At that time, South Africa was preparing itself for the first democratic elections. People who had previously been excluded from the city, moved to Pretoria searching for a better life for themselves and their children, but instead they ended up on the streets.

The TLF’s response to this situation was Potters House, a program for women with children who often gathered outside churches asking for food assistance. However, without the skills needed for work, the streets would become their permanent “home”. A church hall in Burgers Park was used to train these women with basic skills. Parishioners were then invited to employ them once the training was completed. However, their low-income labour could not cover the cost of accommodation in the city. Many of these women were forced to live in townships around the city, far from job opportunities, spending between 60 to 70% of their income on transport, leaving home at 4am and only returning by 7pm, and spending little time with their families. The founders then decided to manage a nearby housing complex, previously inhabited by white people, and to accommodate them. They also built offices for their new projects, with apartments above, converted into subsidized rentals for those who were trying to find pathways out of homelessness.

With many churches in the inner city losing their congregations to “white flight”, the TLF proposed to also use their available spaces for social housing. Around 1997/1998 Yeast City Housing became the housing arm of the TLF. Listening to the homeless community through outreach work, the TLF initiated numerous programs and with God’s assistance, miraculously, spaces became available.

Initiatives

With the spread of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, hospitals started referring people home so that they could die with their families. The situation of the unsheltered people was not taken into consideration. The TLF developed the so-called Gilead and Rivoningo programs to care for homeless people with terminal illnesses or chronic mental conditions. Trained nurses and social workers provided holistic assistance to them maintaining the quality and dignity of their lives.

The Akanani program provides shelter and training for women, men and youngsters who flock to the city from rural areas seeking work. Often, they cannot find it, but are too ashamed to return home. Through outreach, the TLF journeys with them until they are ready to leave the streets. The TLF assists them in finding and keeping their jobs secure by providing them with a home, while monitoring these new job placements. Once a job is protected, they graduate from the program and find their first apartment with the YCH. Lerato House offers young, unaccompanied homeless girls on the streets a safe space, allowing them to finish school.

In 2000, the TLF celebrated its first annual ‘Feast of the Clowns’, which is the biggest inner-city festival, run in and around Burgers Park. The Feast is a playful protest where the challenges of the city’s most vulnerable dwellers are made visible in a colourful way.

The TLF has been extremely successful over the years, with the street in front of the TLF main office becoming a safe space and home for those who are not participating in any program. They have been using the TLFs offices to store their few valuables, to access food, receive health services and to find a space of ‘humanity’ without the random arrests and confiscation of their belongings by Metro police. (*)

The recent utterances by the Gauteng Premier and the clampdown by the Department of Social Development has left the TLF in a very vulnerable state and has emboldened city officials—who see homelessness as a choice and not the result of systemic failure— manifesting in a blatant anti-poor agenda.

Safeguarding

In December 2023, during morning prayers at the TLF offices, there was a scuffle between some TLF staff members and the Metro police, who were confiscating the belongings of the homeless. Tensions were high, as the TLF staff have lived experience of rooflessness and know each destitute person and their individual stories by name. They understood that with Christmas approaching, what the police saw as rubbish were in fact the only possessions the homeless had. To prevent the TLF staff from being jailed,it was explained to the police that what they perceived as rubbish were in fact items such as people’s IDs, medical cards and medication.

The homeless were then allowed to collect their important belongings. Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR), a longstanding alley, were on the scene shortly, trying to stop the eviction, but they were unsuccessful. A court case determined that the city had to find a safe space for this group. This meant that the homeless would then move to shelters in the townships —created with the collaboration of some non-profitable organisations —, thus outsourcing the city’s homeless problem to already overburdened townships. It appears that municipal authorities give priority to tourists and businesses who want a “world class city”, while the townships suffer the consequences of failed government policies. Brand (2021) argues that if we want to protect the homeless from arbitrary attacks by the state, we need to declare safe spaces on the streets as their home, which protects them from eviction under the constitution and the laws.

The over-all vision of the TLF is to promote healthy and vibrant communities, flourishing in God’s presence. Over the past 30 years, the TLF has actively been creating homes for people regarded by society as not worthy of their constitutionally enshrined dignity. Many people believe that homelessness cannot be solved, but literature and the TLF experiences prove otherwise. De Beer (2022: 1-2) states:

“In the City of Tshwane, a collaborative approach between the municipality, non-governmental organisations and the University provided 2 000 bed spaces to homeless people in ten days, in May 2020, something that could not be achieved in ten years… this showed that it was possible to provide decent and viable alternatives to people living on the streets in ways that were supportive of people’s full reintegration into society.”

If only we had the pollical will.

References:

- Brand, D and de Villiers, I. 2021. Street-based people and the right not to lose one’s home, in Facing Homelessness: Finding inclusionary collaborative solutions pp-95-124. (Ed. Valley and de Beer). Aosis. Cape Town.

- De Beer, S (2022): Homelessness IS a Housing Issue: Responding to Different Faces of Homelessness. A City of Tshwane Case Study, in South African Review of Sociology. Published online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2022.2026247

- Kiewit, Lester et al. 23 March 2020. Ramaphosa announces 21-day lockdown to curb Covid-19, in The Mail and Guardian, available online at https://mg.co. za/article/2020-03-23-ramaphosa-announces- 21-day-lockdown-to-curb-covid-19/

* The TLF has come to realise that political will is absent from protecting the lives of the most vulnerable in the City. Therefore, it is currently moving back to its church origins and is restructuring itself to be less dependent on government funding. Any assistance in this turnaround would be much appreciated. To volunteer time or skills to TLF please contact Ms Taryn Mntamo at taryn@ tlf.org.za.