FINDING A HOME

The cross is also the anchor of our hope as it appears in the Jubilee logo embedded onto the lit candle. The lower part of the cross is elongated and turned into the shape of an anchor, which is lowered into the waves and stabilizes the ship amidst the storms.

In addition, the cross is bent down backwards towards the four human figures. This indicates God’s act of compassion, seeking us out and offering surety of hope.

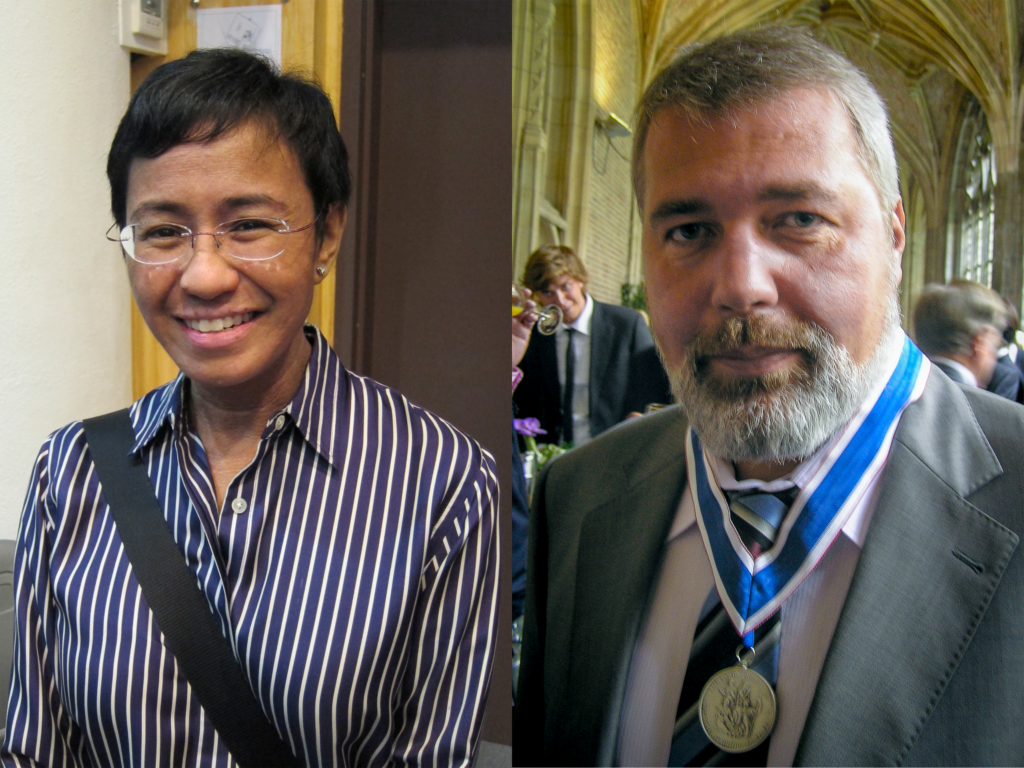

PROFILE • MARIA RESSA

COURAGE AND PERSEVERANCE FOR THE SAKE OF THE TRUTH

In the context of this Jubilee Year, Filipino-American journalist and 2021 Nobel Laureate, Maria Ressa, is celebrated as an outstanding example of courage and vocality, denouncing oppression and corruption. Despite suffering serious attacks and various forms of abuse, she has remained committed to truth and justice.

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

FROM THE very start of the latest conflict, Israel banned foreign journalists from entering Palestine, and particularly Gaza. That has meant that the world has had to rely on reports from Palestinian journalists operating in increasingly difficult circumstances, and on the ‘citizen journalism’ accessed through social media.

The running total of Palestinian journalists killed since October 2023 is 196—and sadly, that total may be higher by the time you read this.

Attacks on Journalists

This censoring of news, for that is what it has been, has had the ability to radically shift the perception of public and indeed political opinion. And yet the risks for journalists are not confined to the Middle East. Back in 2003, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported that the number of journalists killed in the world stood at 42, the highest since 1995. They added that ‘the general trend is towards the deterioration of the working conditions of journalists in periods of armed conflict.’

According to the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), 129 journalists and media workers were killed in 2023, making it one of the deadliest years since 1990, when the IFJ began tracking journalist mortalities. Most of those deaths occurred in the Gaza war.

The ICRC (2006) has said:

“…Covering a war is becoming more and more dangerous for journalists. Added to the traditional dangers of war are the unpredictable hazards of bomb attacks, the use of more sophisticated weapons against which even the training and protection of journalists is ineffective—and belligerents who care more about winning the war of images than respecting the safety of media staff. So many factors that increase the risks of war reporting…”

Let us not think, however, that it is only in instances of war that journalists are under attack.

Censoring the Truth

While there is no overt conflict taking place in the Philippines, for instance, journalists there are under daily threat should they report facts which the government wishes to hide from the population.

Maria Ressa, a Nobel Laureate in 2021 for her services to journalism, is someone who has been threatened with personal injury, with rape, and with death, simply by ensuring that Rappler, the media organisation which she founded in 2012, holds those responsible for corruption accountable for their actions.

The death threats cannot be dismissed as bluster by a government under scrutiny. In November 2009, in the province of Maguindanao, 32 journalists were among the 58 victims massacred and buried in a mass grave by members of the Philippines’ political dynasty, angered by a political challenge.

As we go forward as Pilgrims of Hope in this Jubilee Year, one of our aspirations must surely be to support journalists such as Maria Ressa; to support the very concept of a media able to generate unbiased, honest reports on politics, on conflicts, on our lived experience.

The Unfolding of a Role Model

Journalists worldwide look to Maria Ressa as a role model. She has spent a lifetime bringing truth to power, and the awarding of the Nobel Prize in 2021 has been just one of many prestigious rewards that reflect her commendable efforts.

She was born on 2 October 1963 in Manila in the Philippines. Her family moved to the United States when she was nine years old, and her education there took her to Princeton University. She subsequently returned to the Philippines to study for a master’s degree at the University of the Philippines Diliman. Ressa then worked for CNN, reporting on increasing terrorism threats in Southeast Asia in the 1990s.

In 2012, she helped to co-found the Rappler online news site. She became known as an investigative journalist, defending freedom of expression and spotlighting the abuses of power, violence, and growing authoritarianism of President Rodrigo Duterte’s regime. Perhaps one of the most dangerous aspects of her work was her focus on President Duterte’s so-called anti-drug campaign.

As victims themselves of fake news on social media, she and the Rappler agency have reported fearlessly on the way that social media allows and facilitates the distortion of facts, particularly in the political arena.

Maria Ressa became known as an investigative journalist, defending freedom of expression and spotlighting the abuses of power.

That bravery has led to the threats to her freedom and her life.

Accounting to Power

Maria and her Rappler staff found themselves under attack as soon as Rodrigo Duterte came to power in 2016. The new president enjoyed popular support, but Rappler revealed alleged evidence of corruption and the widespread use of fake social media accounts to manipulate the news. One Rappler focus point was Duterte’s violent war on drugs. The government’s own estimates record that over 6,000 people died at the hands of the police. That number could in fact be doubled—a figure even Duterte would be hesitant to boast about.

And so, in 2018, charges were filed against Rappler in a Philippine court and its business licence was revoked. Allegations were made about tax offences by both Ressa and Rappler. Ressa was granted bail and has denied and fought back against all charges made against her and Rappler.

In 2021 she and the Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov, editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta, which investigates human rights abuses, were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, for “their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.”

Amnesty International’s Agnès Callamard (2021), said in response to the award:

“Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov’s Nobel Peace Prize win is a victory not only for independent, critical journalism in the Philippines and Russia, but for the fight for justice, accountability, and freedom of expression all over the world.”

She added, “For more than three decades, Maria Ressa has worked tirelessly as a journalist in the Philippines, carrying out vital investigative reporting on corruption, abuses of power, and human rights violations in President Rodrigo Duterte’s deadly so-called war on drugs. As the co-founder of Rappler, a highly lauded and uncompromising online news site, she’s opened the world’s eyes to the brutality and pervasive impunity in the Philippines. Put simply, she is a global icon for press freedom.”

Attacks from Social Media

Ressa’s Nobel citation also noted that “she and Rappler have also documented how social media is being used to spread fake news, harass opponents, and manipulate public discourse.”

Social media can be most threatening. The most harmless and unbiased post can elicit scorn and threats.

Since that citation, social media has been most cruel to her. The International Centre for Journalists, a non-profit professional organisation which promotes journalism worldwide, issued a report (ICFJ 2021) on the deadly (almost literally) onslaught Ressa has faced, again because of—that phrase which follows her—her “efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.”

Price of Honesty

Were Ressa to be convicted on all the charges she faces, she could spend the rest of her life in a Philippines jail—and this solely for publishing, as this report says, “public interest journalism.”

The report suggests the evidence points to the fact that the online violence targeting Ressa “…has offline consequences. It has created the enabling environment for her persecution, prosecution, and conviction. It also subjects her to very real physical danger.” Ressa is not alone, of course. There are journalists around the world facing trumped-up charges and suffering the kind of social media torture that Ressa has been subjected to.

Those journalists — while concerned enough to try to persuade Ressa not to return to the Philippines (even though she ignores their pleas) — are nevertheless aligned with her commitment to get the truth exposed.

Julie Posetti (2020) said: “The Philippines is one of the deadliest countries on earth to be a journalist, and my gravest fear is that Maria Ressa will be the next murder victim of President Rodrigo Duterte’s regime.”

She added, “Ressa is relentlessly optimistic, and the sense of responsibility she has for her team at Rappler… is unwavering. She was never going to abrogate what she believed was her duty.” And of course, Ressa went back to the Philippines and has continued to carry out that duty.

“Relentlessly optimistic”

This is not a phrase we might expect from a friend of this remarkable woman. And yet optimism is implicit in Ressa’s continued determination to fulfil that Nobel Prize citation: “for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace”.

Her bravery should be an inspiration not only to fellow journalists but to all of us who hope for an end to tyranny and for peace to take root around the world.

Pope Francis (2024) said: “no one comes into this world doomed to oppression: all of us are brothers and sisters, sons and daughters of the same Father, born to live in freedom, in accordance with the Lord’s will,” adding that Christians “feel bound to cry out and denounce the many situations in which the earth is exploited and our neighbours oppressed”.

Maria Ressa continues to denounce oppression. Her bravery should be an inspiration not only to fellow journalists but to all of us who hope for an end to tyranny and for peace to take root around the world. Her voice and ours count. Together on our Pilgrimage of Hope in 2025, may we take positive steps to make it happen.