FINDING A HOME

The cross is also the anchor of our hope as it appears in the Jubilee logo embedded onto the lit candle. The lower part of the cross is elongated and turned into the shape of an anchor, which is lowered into the waves and stabilizes the ship amidst the storms.

In addition, the cross is bent down backwards towards the four human figures. This indicates God’s act of compassion, seeking us out and offering surety of hope.

CHALLENGES • AFRICAN RESTORATION

THE JUBILEE AND THE AFRICAN DREAM OF EMANCIPATION AND RESTORATION

This reflection offers a look at the Jubilee from a Black theological perspective, and questions whether the Jubilee provides an unrealistic ideal or a radical social-spiritual viewpoint which is attainable in the African context by means of the Good News embodied in Christ.

BY FABIAN ASHWIN OLIVER | YOUTH MINISTER, JOHANNESBURG

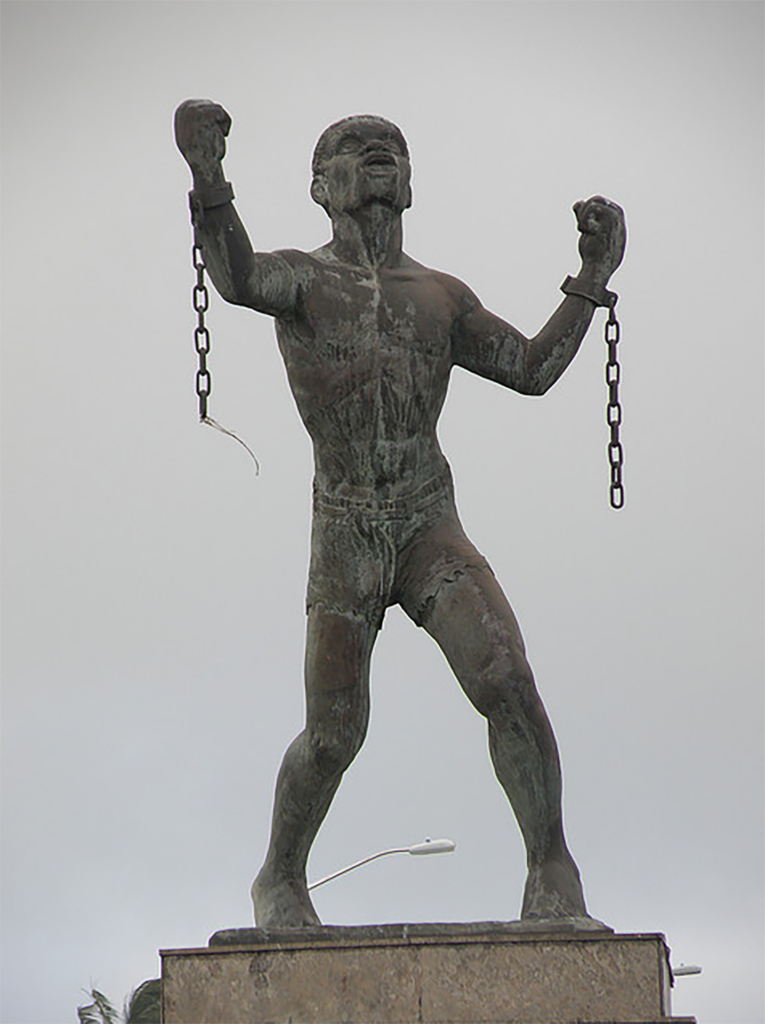

THE YEAR of Jubilee marks a significant moment for the Church and also a landmark occasion for thoughts on Africa, its politics, the promises of freedom and restoration in a continent still entrapped in the viscous legacy of colonialism, racism, tribalism, and in new modes of Africanised forms of oppression often championed and spiritualised by some members of the institution of the Church.

Attainable Utopia?

Despite the Jubilee being recorded in several parts of the Hebrew Bible, there is scholarly contestation with regards to whether it was ever practised or fully realised by the Israelite people. Some arguments suggest that there is little evidence in the Scriptures that God’s call for a Jubilee was properly observed. On the contrary, some suggest that if the Jubilee was regularly practised in those times, there would have been no need to explicitly mention it (Lindsey 1985:211). In truth, we will never know if the Jubilee was ever realised; it is likely though that the Jubilee arose from a radical ideal for a more just world from the heart of Godself, embedded in the spirituality of the moral codes of Leviticus 25, but never realised due to human limitations (Faley 1990:78).

Nevertheless, it is the spirit of the Jubilee which remains pertinent for us today. Muswubi (2024:2-3) describes the guidelines for the call for a Jubilee with the five R’s:

- Rest, as a physical necessity; it involves allowing the land to lie unplanted, to preserve the health of the soil. During this period, agricultural activities such as planting, harvesting, and gathering are prohibited. Its key lesson is cultivating trust in God’s provision.

- Release, as a psychological necessity; it entails not only resting from agricultural labour, but also emancipating slaves, forgiving debts, and halting interest on subsistence loans. Its primary lesson is fostering forgiveness.

- Relief, as a socio-economic need; it complements rest and release, addressing both the land and those marginalised. It entails permitting the poor to harvest self-grown crops, ensuring fair wages for bonded labourers, offering loans with minimal or no interest, and providing equitable legal justice for the disadvantaged.

- Return involves letting the land rest while restoring ancestral property to its original owners, and providing wholistic return to the work exploits, land, ownership, and people.

- Finally, Restore, as a spiritual need, encompasses physical, psychological, and socio-economic dimensions. It involves renewing personal and collective dignity, while also restoring four key relationships: with God, self, others (family, tribe, nation), and nature.

African Jubilee

The African context offers us a twofold paradigm on the Jubilee: one of a utopian vision detached and yet tethered to neoliberal capitalism and the continuation of impoverishing Africa. The second offers us the spirit of an unrealised attainable ethos where justice, emancipation, and restoration are possible for this lifetime and beyond.

The Jubilee arose from a radical ideal for a more just world from the heart of Godself

Let us consider the former dimension first. In her novel Migritude (a colourful combination of the words “negritude” and “migrant”), Indian-Kenyan author Shailja Patel powerfully critiques the exploitation of Africa by the West, using a language of resistance and anger. She compares Africa’s debt to the global North to the situation where an intruder forcibly takes over one’s home, mortgages it multiple times, and then demands repayment with interest. Patel also highlights the irony of how people appreciate African culture and rhythms, yet fear African voices that challenge the status quo (Patel 2010:37-39).

We must ponder what true restoration and emancipation look like in Africa. What does the Jubilee call for, amid Africa’s latent poverty and suffering, with African leaders who use yesteryears’ tactics of maintaining power, and with numerous Church leaders remaining silent on political and social issues masked with the emphasis on the spiritual world? The cry of the earth due to the ongoing ecological catastrophe continues to echo the cry of the poor who are in need of Jubilee. The cry of the people of Sudan, Congo, or Haiti, reverberates the cry of the people in Gaza, desperate for the day of peace, of restoration to their homeland, and of liberation from all which oppresses them.

An attainable Jubilee is reigniting God’s call for a radical restoration and emancipation of our land. It is honouring the Sabbath’s call to rest and offering rest as a resistance to the corporate mechanization of people’s bodies towards profit (an act of alienating from self and family). Indeed, Jubilee is not just an ancient practice but a prophetic call for freedom, justice, and restoration of Black people and other marginalized communities. It represents God’s desire to heal the wounds of oppression, restore economic and social equity, and offer spiritual renewal.

Decolonial Feminist, Françoise Vergès offers insight which I find helpful in articulating the joy of God’s call to Jubilee. She says that there is power in united resistance and joy in the pursuit of restorative justice. She invokes us to envision a utopia that fuels our resolve to challenge oppression, offering an invitation to liberating aspirations under the belief that someday, we will all be free (Forrester 2021).

Jesus, the embodied Jubilee

In Jesus, we discover the embodied Jubilee that calls us to a different way of being and living in our world. Jesus’ own prophetic mission to bring good news to the poor, freedom for prisoners, healing for the blind, and release of the oppressed, and thus announcing the year of the Lord’s favour, are reminiscent of the call to Jubilee (Luke 4:18-19). Even the Lord’s Prayer offers a clause on the forgiveness of “sins”, which was formally understood as forgiveness of “debt” (Matthew 6:12), similar to his parable of the unforgiving debtors (Matthew 18:21-35).

The Jubilee represents God’s desire to heal the wounds of oppression, restore economic and social equity, and offer spiritual renewal.

The call to Jubilee is indeed not a once-off event, but a transformative ethos calling us to confront areas of restoration, rest, justice, and peace. For Africa, this means amongst other things, contemplation on the vicious legacies which impoverish families, kill people and create false hierarchies based on anti-blackness, tribalism, sexism, and homophobia. The Jubilee of God is one of witnessing to God’s favour on all creation without our merit (Grace!). Jubilee is an invitation to reorientate ourselves towards God’s justice as opposed to our own systems. Jubilee offers a living at the edge of reality beyond the binary of oppressed and oppressor, towards a third space of living at the demise of the world of domination and obliteration.

And Africa shall be saved

Rooted in various lexicons, the word Jubilee is a call for joy and celebration. This joy, for the African people, is one of rain after a long drought. In her song, Mayine (2010), which loosely translates from Xhosa to English as “may it be” or “let it rain,” singer and activist Simphiwe Dana offers a jubilant plea for rain which comes with blessings, freedom, and transformation. Dana voices emotions of melancholy, anguish, and a longing for freedom in the first part of the song, but in its second part, she turns to hope and to a promise of renewal.

Mayine can be interpreted as a refrain of Christian Jubilee as it embodies the biblical values of freedom, restoration, and empowerment, while also promoting justice and reconciliation within the community.

In this precious year of Jubilee, Mayine on the African continent reignites in us God’s love and His promise of freedom, rest, and joy for everyone. May the waters of the Jubilee wash away the colonial lure to optimize greed and exclusion, based on difference, towards an ethos nourished in God’s providence and a call for a social order that is more just, loving, and peaceful. Mayine!