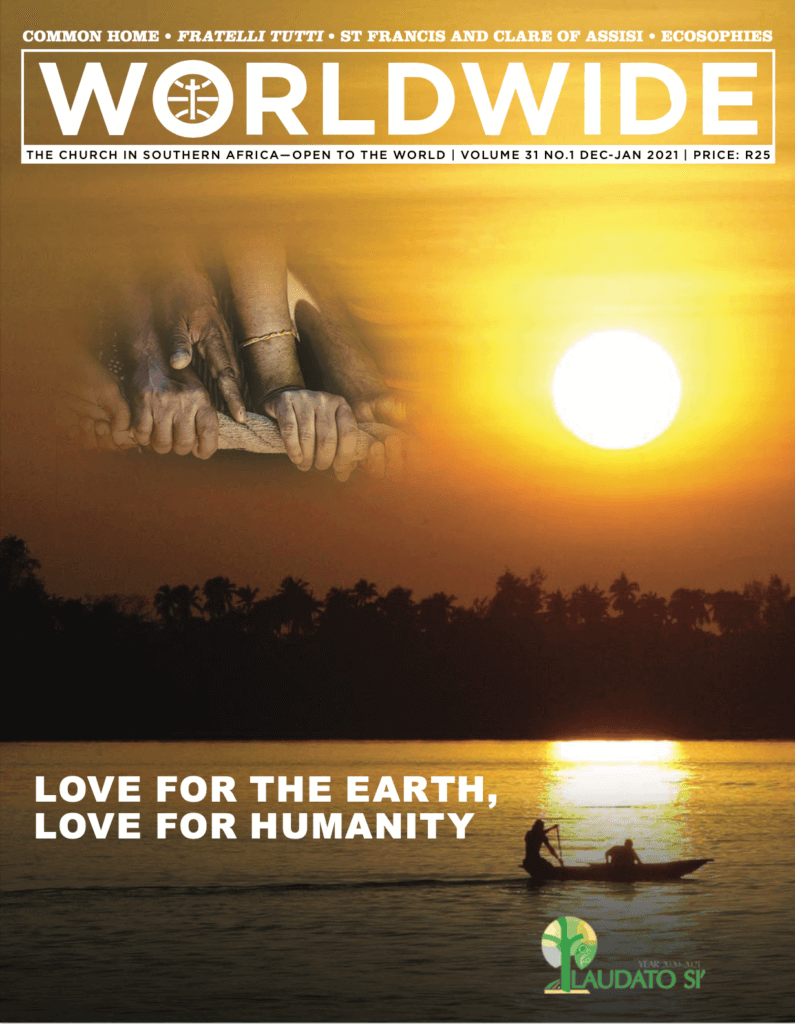

Love for The Earth,

Love for Humanity

The bright light of the rising sun represents the luminosity, the beauty inherent in each human being and our capacity to transform evil into good and to establish authentic human relationships. The closeness of the celebration of Christmas envisions the coming of the Light and Peace for the world, the One that fulfils the greatest aspirations of any person and leads us all to God.

Could the Pandemic Create a Less Exclusive Economy?

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the global crises that were already there, the recognition of a dysfunctional economy and the driving force behind highly unequal societies — which favour new paths, fears and hopes, but the future remains unknown.

IT IS impossible to predict the changes that will come from this tragedy, because “there are too many variables and uncontrollable interactions,” says Brazilian economist Ladislau Dowbor, a graduate professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, who sees the corona virus as a crisis aggravated by a series of other factors.

Neoliberal economic policies have tried to reduce the role of the State and adhere to a fiscal austerity that has limited investments in public health systems. Now all of this has a heavy weight and the responsiveness to the pandemic has declined. Inequality — reflected in income, housing, poor sanitation, overcrowding and long trips in public transport — has favoured the spread of the virus and its lethal consequences. The poor distribution of the world’s wealth erodes the defences of society: liberal economists acknowledge this as it has been proved in previous epidemics and environmental disasters.

The world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a total of $850 billion, which distributed per person would ensure $3 700 per month for each family of four, Dowbar noted. Addition- ally, in the tax havens there are $200 billion.

In his book, An age of unproductive capital, the economist Ladislau Dowbor (2019) devotes part of his study on the draining of resources for the financial system, a system that absurdly enriches a few, impoverishes the majority and nothing gets produced.

Reducing the concept of economy to finance alone and not for the benefit of people ends up being a barrier to development and generates the frustrations that result in protests, uprisings, occupations, marches and rebellions.

Many economists are seeking answers to the systemic challenge of the four converging crises: environmental disaster, explosive inequality, financial chaos, and the corona virus. The key is to adapt the decision-making process to define how to use resources and replenish the economy at the service of the common good, Dowbor concludes. Covid-19 has changed all of the norms by forcing the disruption of nonessential activities, isolating people in their homes, and paralysing the economy.

Some changes were imposed. Many governments temporarily abandoned their fiscal austerity policy and approved a ‘war budget’ that allowed them to allocate a considerable percentage of GDP in emergency aid to families, workers and businesses.

The most impressive sums are those of the United States: the government announced a package of two trillion dollars, 10% of GDP, to offset losses and protect companies and workers against the sudden loss of income. Those measures are reminiscent of the British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), who proposed state intervention to stimulate aggregated demand and sustain the economy and employment.

These are pragmatic measures, to avoid an explosive increase in hunger, social seizures and the destruction of the economic system that would make its post-pandemic recovery very costly. Expecting a permanent change in economic policy, a return to Keynes’ proposal can be an illusion. The exceptional expenses will represent a brutal increase in public debt that will serve as an argument for the intensified return of austerity, already claimed by many economists.

In any case, reinforcing the State and public health for the future appears as a logical consequence of this crisis. Pandemics will remain a permanent threat for a long future. The hope of many is that the tragedy of the pandemic, the dimensions of which are still incalculable, will move humanity to the point of reducing consumerism, promoting solutions for the climate crisis and for the inequality that is now considered unacceptable.

No political or social forces appear to ensure favourable decisions to such changes in the future; the trend is clearly contrary. The corona virus forced the closure of borders, deepening nationalism that was already gaining strength and has affected national co-ordination, which would have been useful in combating the pandemic.

With regards to employment, there is a huge destruction in progress and “nothing guarantees future restoration,” says José Dari Krein, a researcher at the Centre for Trade Union Studies and Labour Economics at the University of Campinas, in southern Brazil. Evidence of this are the definitive bankruptcy of many small companies in a ‘chain effect’,

the foreseeable adoption of technologies and the re-organization of businesses to reduce the labour force and policies of the

current government.

The president of the Unified Workers’ Central (UWC, the largest union in Brazil), Vagner Freitas, in return, identifies “a moment of opportunity, of solidarity.” The crisis values collective solutions, “strengthens the union by rescuing its role of negotiating agreements”, after some years of deterioration of labour and union rights. The pandemic calls into question many negative policies and affirms “the need to build strong nations — not just strong corporations — investments in science, an efficient state to provide services to society and not only to capital,” concludes the unionist.

(Mario Osava, Rio De Janeiro, available at https://www.jpic-jp.org)

Could the Pandemic Create a Less Exclusive Economy?

THE COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the global crises that were already there, the recognition of a dysfunctional economy and the driving force behind highly unequal societies—which favour new paths, fears and hopes, but the future remains unknown.