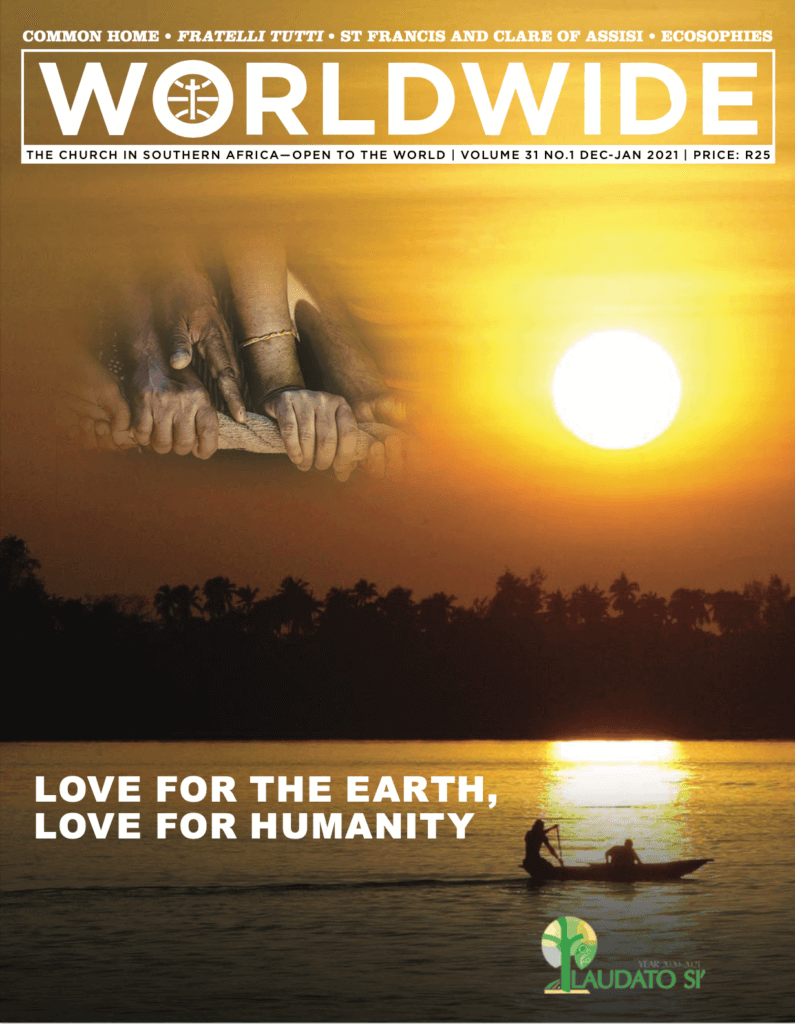

Love for The Earth,

Love for Humanity

The bright light of the rising sun represents the luminosity, the beauty inherent in each human being and our capacity to transform evil into good and to establish authentic human relationships. The closeness of the celebration of Christmas envisions the coming of the Light and Peace for the world, the One that fulfils the greatest aspirations of any person and leads us all to God.

in as much as it seeks the common good, House of Parliament, Cape Town

Hiding Our Light

WHEN ANDREW Mlangeni, the last surviving Rivonia trialist who spent 27 years in jail with Nelson Mandela, passed away recently, there was some initial uncertainty about whether or not he was a Catholic. Soon enough, tributes and obituaries confirmed that he was, as did the fact that he was buried by Archbishop Buti Tlhagale of Johannesburg.

It seems, though, that Mr Mlangeni’s Catholicism was not particularly widely known or celebrated by fellow Catholics. No mention of it was made, for example, in the statement of condolence published on the Bishops’ Conference website. In fact, we generally don’t seem to be very interested in knowing which prominent figures in our public life

are Catholics.

In 1997, when we started the Catholic Parliamentary Liaison Office, Fr Smangaliso Mkhatshwa (a former Secretary-General of the Bishops’ Conference) was an ANC MP. He undertook to try to compile a list of Catholics in Parliament so that we could introduce ourselves and the work of the CPLO to them, and maybe set up some kind of cross-party group of Catholic MPs of the kind that exists in some European and African countries.

After a while he gave up — apart from personal knowledge, there was simply no way of finding out the religious denominations, if any, of parliamentarians. Over the years since then we have occasionally been told that such-and-such an MP or Minister is a Catholic, only for it to turn out that he or she is or was married to a Catholic; or was once or twice seen at Mass somewhere.

Sometimes we are taken completely by surprise. The late Bishop Zithulele Mvemve once asked us if we had had any dealings with a Catholic MP who was very active in his diocese. It turned out that we knew the MP,

but would never have guessed that he was Catholic — his name was

Ismail Mohamed.

It also happens every now and then that an MP before whose committee we are making a submission rather grumpily remarks, “Well, I am a Catholic and I don’t agree with what you’re saying” — and, it has to be said, once or twice we have discovered that a particular MP or Minister is Catholic, and found ourselves rather wishing that we had been left in ignorance on that point.

Does this kind of religious anonymity matter? Certainly, it is a healthier situation than that which prevails in some parts of the world, and in some parliaments, where people are pre-judged and pigeon-holed on the basis of their faith or denomination — or where Catholics are assumed to be supporters of one party and Evangelicals or Protestants, another. We would not want religious adherence to become politicised, or sectarianism to invade our politics.

At the same time, it would be good to see more politicians bringing their religious values into the work they do as public representatives and lawmakers. For example, the principles of Catholic Social Teaching have a huge amount to contribute to policy debates around equality, the elimination of poverty, human rights issues, and the same applies to the social teachings of other faiths.

Unfortunately though, as we saw during the American presidential election campaign, it is all too easy for a politician’s religion to become an ecclesiastical football as well as a political one. Joe Biden’s Catholicism was seen by some as a reason to support him; historically, despite making up around 25% of the US population, only one Catholic, John F Kennedy, had made it to highest office — but his support for legal abortion led others to accuse him of betraying his Catholicism. One bishop went so far as to say that, for the first time in many years, “there is no Catholic on the Democratic Party ticket!”

Something similar happened with the controversial appointment of Amy Coney Barrett as a Justice of the US Supreme Court. More media attention seemed to be focused on her religion and her sometime membership of a conservative Catholic fellowship than on her experience and standing as a judge. Similarly, many analysts have drawn attention to the fact that six of the nine Supreme Court Justices are Catholic, as if this necessarily means something when it comes to how they might decide a case. Here in South Africa very few of us have any idea at all about the religious beliefs, if any, of our judges and, with a possible exception in the case of Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, who has made no secret of his evangelical Christianity, there has never been a feeling that those beliefs would influence a judge’s findings.

We certainly don’t want to head in the direction of the US and have our political and judicial leaders’ religious affiliation dragged through the mud; but at the same it would be good to see more politicians and people in public life being open about how their religious or spiritual convictions have sustained them in the often difficult and pressurised worlds of politics and public service.

Could the Pandemic Create a Less Exclusive Economy?

THE COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the global crises that were already there, the recognition of a dysfunctional economy and the driving force behind highly unequal societies—which favour new paths, fears and hopes, but the future remains unknown.