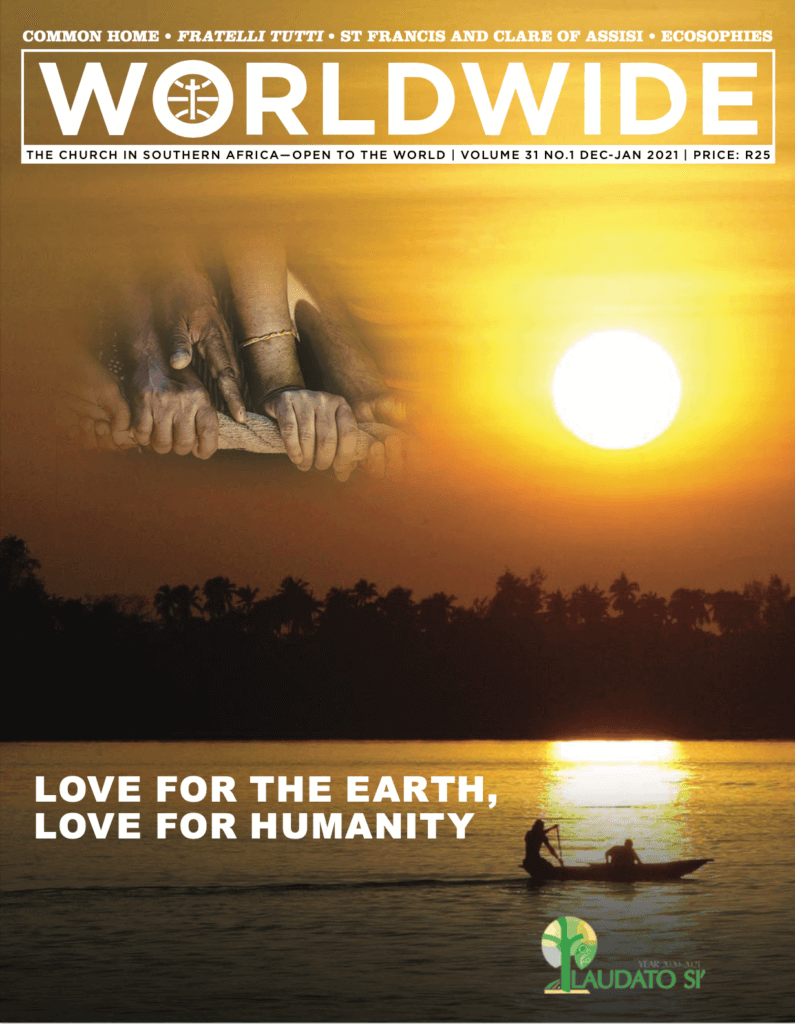

Love for The Earth,

Love for Humanity

The bright light of the rising sun represents the luminosity, the beauty inherent in each human being and our capacity to transform evil into good and to establish authentic human relationships. The closeness of the celebration of Christmas envisions the coming of the Light and Peace for the world, the One that fulfils the greatest aspirations of any person and leads us all to God.

THE CRY OF THE EARTH, THE CRY

OF THE POOR

The article reflects on the legacy of St Francis and St Clare, which has been so influential in shaping Catholic thinking today

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | AUTHOR AND CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI, SCOTLAND

WHEN JORGE Mario Bergoglio of Argentina was elected leader of the Catholic Church in March 2013, he chose the name Francis. No Pope had ever used this name before, but the new Bishop of Rome told the waiting media that during the election, he had been thinking of the poor and so, when his appointment was confirmed by that puff of white smoke, he felt that Francis had to be the name by which he would be known.

He explained it was because St Francis “is the man of poverty, the man of peace, the man who loves and protects creation.”

In the years since, Pope Francis has pulled the principles of St Francis forward eight centuries to place the environment and the poor at the heart of his papacy. The encyclicals Laudato Si and Fratelli Tutti ask us to hear the cry of the poor and the cry of the earth, and each takes words and ideas straight from the heart of the Italian saint. Those of us who were raised with images of a gentle St Francis, birds perched on his outstretched arms, squirrels attentive at his feet, have perhaps been jolted by Pope Francis into a better understanding of the reality of the man who initiated a doctrine of nonviolence 800 years before the word became a social media hashtag, who promoted care of our common home, supported the poor, and who practised interreligious dialogue when the Church itself seemed hell bent on slaughtering

those of other faiths.

Some saints from the past are wreathed in myth and legend, but St Francis of Assisi is well documented. That may be because the city of Assisi in central Italy was already in the 12th and early 13th centuries a sophisticated—if fractious—community that kept records of its citizens. It is also because in 1228, just two years after Francis’ death, Pope Gregory IX asked the monk Thomas of Celano to write a biography of St Francis. Using material gathered from Francis’ friends and followers and his own personal knowledge, the record was finished within a year. A later version was written in 1246. Thomas also compiled a book of the collected miracles of St Francis, and he wrote a biography of St Clare of Assisi. This abundance of information shows how quickly St Francis was recognised as an important figure in the Church, and makes the man’s philosophy and teaching unusually available, given the eight centuries gap.

Francis Bernardone did not start life with the name ‘Francis’. His father, a wealthy cloth merchant, was away from home on business when his son was born in 1181. His mother had the child baptised Giovanni—John in English—in honour of St John the Baptist. Returning home in 1182, Pietro Bernardone was evidently greatly displeased. The name suggested to him that his son would grow up to be a man of the Church, while he was hoping for a successor in the lucrative cloth trade. Much of that trade was with France, and so he renamed his son Francesco (Francis).

Growing up with all the benefits that the cloth trade brought to the Bernardone family, it is no surprise that Francis did become the merchant Pietro hoped for. But as wealthy youngsters sometimes do, he had his ‘tearaway’ phase, instigating the wildest of wild parties. Thomas of Celano pulled no punches in his biography, writing “In other respects an exquisite youth, he attracted to himself a whole retinue of young people addicted to evil and accustomed to vice.”

He perhaps spent more than he brought into the business, and he was vainly ambitious for a place in the ranks of the aristocracy. When war broke out between Assisi and neighbouring Perugia, he headed for the battlefield. Rank and file soldiers from Assisi were massacred, while those who might fetch a ransom were imprisoned. The Bernardone wealth was legendary and Francis spent a year chained in a dank dungeon.

Saints are often comfortingly sinners before turning to good works, and this spell in a dungeon would seem to have been a good time for a Damascene moment to change Francis’ lifestyle and thinking.

However, after he was released on payment of a ransom, he continued to enjoy the high life. He even grasped another opportunity to get the much-desired knighthood at the start of the Fourth Crusade, an armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III to recapture the Muslimcontrolled city of Jerusalem.

To the modern mind, the Crusades may suggest noble (if misguided) faith-driven campaigns. Francis Bernardone set out on the Fourth Crusade more anxious to show off his expensive, gold-plated armour than to lend his strength to the cause.

It was then that the vision came. Just a day from home, Francis had a dream in which God told him to return home and change his ways. He responded to the dream, but this was not an overnight conversion. Francis was a complete novice in religious terms. He had to extricate himself from the family business, from his life of extravagance, from the secular world he’d loved for the first 25 years of his life.

There were hard lessons. He took cloth from his father’s business to fund the repairs of a church, leading to a rift with his family. This wasn’t just theft from the family business: Francis still lacked understanding that the message from God was not literally to renovate a ruined building but to rebuild the Church itself, which at the time was experiencing corruption.

The local bishop helped him understand what his mission really was. It was then he could renounce everything and start a new life, preaching a return to God and obedience to the Church. Joined by others who wanted to share this simple life in which he relied on God to provide all, he turned to the Gospel for guidance and took as the Rule for this ‘brotherhood’, three commandments found when he randomly opened his Bible—the command to the rich young man to sell all his goods and give to the poor, the order to the apostles to take nothing on their journey, and the demand to take up the Cross daily.

These would be the guiding rules of the Franciscans — a brotherhood rather than a religious order. A brotherhood that was inclusive of people from every walk of life and all creatures sharing our common home.

He preached to the birds; he rebuked the wolf; he kissed the leper. The brothers followed biblical teaching and went out in pairs. They gave to the poor, those even more poor than themselves. The cry of the poor, the cry of the earth, the response of nonviolence to those who attacked them as madmen: this was revolutionary. It is still revolutionary—as Pope Francis is finding eight centuries later, while trying to convince 21st century society of the need to respond to our world in a similar way.

Perhaps St Francis’ most revolutionary act was to make direct contact with the Muslim leader during the Fifth Crusade in an effort to make peace. Today, Pope Francis calls the kind of meeting his namesake sought with al-Malik al-Kamil, the Muslim Sultan of Palestine, Syria, and Egypt, “the culture of encounter”. In 1219, no such phrase had been coined. No such meeting had ever taken place before.

During the devastatingly bloody siege of the Egyptian city of Damietta, Francis and one of his brothers, Illuminatus, set off to meet the Sultan. Illuminatus spoke some Arabic, but had al-Kamil’s guards not mistaken the pair for Muslim holy men, this could have been nothing less than a suicide mission. Ushered into the presence of al-Kamil, Francis talked to him through interpreters about his faith, and made a plea in the name of God for peace between the warring factions. Although his advisers wanted to kill Francis and Illuminatus, al-Kamil was evidently a man who preferred prayer to the violence of war. He recognised holiness in Francis and invited the two Christians to be his guests. Whatever conversations took place during that seven-day stay, neither converted to the other’s faith, but Francis was subsequently more open to the other,

to the different.

Today, Catholic social teaching encourages interreligious dialogue.

There are echoes of St Francis’ mission to see the Sultan in the huge strides towards co-operation between faiths and peoples engendered by the document entitled, Human fraternity for World peace and living together, signed in February 2019 by Pope Francis and the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar Ahmad Al-Tayyeb in the United Arab Emirates.

Pope Francis’ latest encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, seeks to inspire an acceptance of that ‘other’, recognising that people of all faiths and none, are nevertheless all brothers and sisters together.

Perhaps Pope Francis has also looked to the 13th century Francis for a response to the role of women in the Church. Thirteen years younger than Francis Bernardone, Chiara (Clare) Offreduccio was one of his first followers when he took to the religious life. Like Francis, she was from a wealthy family. In his wilder days, he may well have envied that aristocratic dynasty with its large palace in Assisi and a castle

on Mount Subasio.

Clare’s mother, Ortolana, was very devout and had undertaken pilgrimages to Rome, Santiago de Compostella, and the Holy Land—major journeys in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, especially for a woman. She must have had a strong influence on all three of her daughters, and Clare in particular was a prayerful child. She was in her teens when she heard Francis preach during a Lenten service at the Church of San Giorgio in Assisi. She asked his advice on how to live the Gospel, and on Palm Sunday, 20 March 1212, she left her father’s house with an aunt and another companion and went to the chapel of Porziuncula to meet Francis. Just as he had done, she laid aside her expensive clothes, put on a simple robe and her hair was cut.

Of course, her father tried to force her to come home, but she clung to the altar, saying she would have no other husband but Jesus Christ. Her sister Catarina (who took the name Agnes) joined her, and soon other women moved into the small building created for them beside the church of San Damiano. They became known as the Poor Ladies of San Damiano, living a life of poverty, austerity and seclusion.

What makes Clare remarkable for the age in which she lived is that she wrote the Rule for Life for her Order, the first set of monastic guidelines known to have been written by a woman. We might reflect that eight centuries later, women’s role in the Church is still debated. In 1994, Pope John Paul II erected strong barriers against a more inclusive attitude, and even Pope Francis has been accused of not listening to the cry of women.

This is not to suggest that the followers of Clare led a feminist-centred existence centuries ahead of their time. Unable to share the same ministry of Francis’ followers in preaching around the countryside, the Poor Ladies of San Damiano lived an enclosed life, carried out manual labour, prayed, slept on the ground, walked barefoot, and adhered rigidly to their vow of strict poverty. However, having at first been directed by Francis, in 1216 Clare accepted the role of abbess. This gave her greater authority, and the order was not obliged to obey a male hierarchy.

Of course, she revered Francis, whom she saw as her spiritual father. After his death on 3 October 1226, she continued to expand her order throughout Europe, and after her own death on 11 August 1253, that order became known as the Poor Clares. Successive Popes had wanted the Order’s vows of extreme poverty to be diluted. She disagreed, and she won. Both St Clare and St Francis embraced a theology of joyous poverty in imitation of Christ. The man who took the name Francis for his papacy perpetuates their legacy.

Could the Pandemic Create a Less Exclusive Economy?

THE COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the global crises that were already there, the recognition of a dysfunctional economy and the driving force behind highly unequal societies—which favour new paths, fears and hopes, but the future remains unknown.