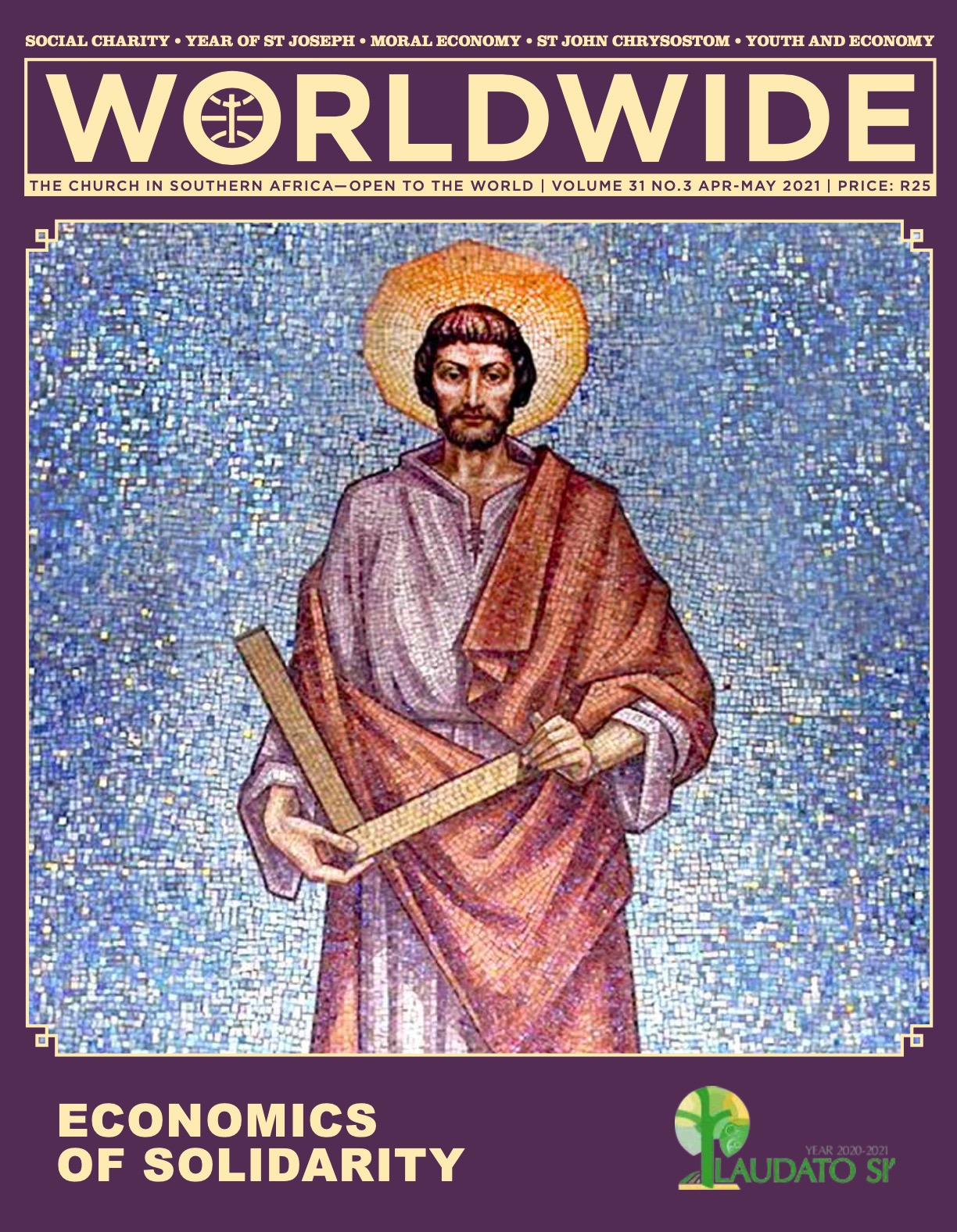

St Joseph and The Dignity of Human Work

We are celebrating the Year of St Joseph. He is, for us Christians, an example of honesty and fidelity, a model of the father figure in the family. He is the humble and firm man who sustained the Holy Family through very difficult situations. This mosaic, portraying him as a carpenter, reminds us of the dignity of human labour. Through work, we become collaborators in the building of society, contributing to it with our various talents. Job creation and sharing of opportunities need to become part and parcel of a new economics of solidarity. Social charity, sustainability and respect for the environment will be integral elements of that model that aims at respecting the dignity of every person.

INSIGHTS • SOLIDARITY

following a request by President Ramaphosa to President Díaz-Canel of Cuba.

[Photo: GCIS – Flickr]

COVID-19: An Invitation To Solidarity

BY MIKE POTHIER | PROGRAMME MANAGER, SACBC PARLIAMENTARY LIAISON OFFICE

A LOT has been written about how COVID-19 has exposed the inequalities in our society, both here in South Africa and around the world. In many ways, it has also extended the gap between rich and poor. People in low-income or casual employment, for example, were more likely to have lost their jobs, and of course, less likely to have had savings or reserves to tide them over until the re-opening of the economy.

Poorer people often live in crowded accommodation — in Cape Town there was a report of 47 people sharing a single house in Mitchell’s Plain — and have to travel by taxi; they don’t have the luxury of private medical care when they fall ill; and due to a lifetime of sub-optimal nutrition they have high rates of some of the co-morbidities that can make COVID quickly fatal, such as diabetes, high blood-pressure, and obesity.

Studies in the USA have shown that African-Americans were disproportionately affected, and in the United Kingdom working-class, inner city communities suffered more than their middle-class, suburban counterparts.

None of this is surprising and the causal factors, some of which I’ve mentioned, are pretty clear. However, it is interesting to look at how our country responded to the socio-economic effects of COVID, firstly, in the steps taken by the government and, secondly, in the more organic responses of ‘ordinary’ people.

The government quickly announced that it would provide a ‘special relief of distress’ grant of R350 per month, aimed at people who had no income and who were not already receiving one of the other social grants. Government also instituted the ‘temporary employer/employee relief scheme’ (TERS), operated by the Unemployment Insurance Fund. This scheme provided funds to help employers to pay the wages of employees who had to be sent home as a result of workplace closures.

These were both very worthwhile interventions, despite the fact that they ran into problems when it came to implementation (once again, our plans are good, but our capacity to bring them to reality is lacking.) However, they were always going to be short-term steps. Before COVID hit us, the economy was already in the doldrums, and the government was having to bor- row more and more each year to meet its budget. All the extra cost of grants has just added to the amount of debt we are racking up as a country. the simple fact is that, when a disaster like COVID hits, the state cannot manage the response on its own.

This is where we ordinary people come in. Perhaps one day someone will write a thesis on how churches, community organisations, clubs and societies of all kinds, and thousands of individuals, spontaneously took up the challenge of looking after their neighbours in need. This was a textbook expression of the value of solidarity, which Pope Francis spoke about in his recent encyclical, Fratelli Tutti (FT):

“Solidarity finds concrete expression in service, which can take a variety of forms in an effort to care for others. And service in great part means ‘caring for vulnerability, for the vulnerable members of our families, our society, our people’” (FT 115).

I’m sure we can all think of examples of the ‘solidarity of service’ over the last year. One interesting development was the emergence of Community Action Networks, which paired wealthier residential areas with poorer ones, and in which assistance measures were jointly decided upon; these were a step beyond simply the rich giving to the poor. There were also numerous efforts within low-income communities; people who were not going to work, for example, spent time organising feeding schemes for children or helping to run neighbourhood kitchens. Restaurants and hotels, without customers due to the lockdown, started cooking for people in need in their areas.

These initiatives were undertaken without waiting for government to give the go-ahead or for million-rand corporate sponsorships. COVID showed us what people can achieve when their sense of solidarity is awakened.

The challenge now is to take it to the next level. If we say that COVID has exposed the inequalities in our world then surely we must ask how, after COVID, we can avoid slipping back into a meek acceptance of such inequalities. Because, as Pope Francis tells us,

“Solidarity means much more than engaging in sporadic acts of generosity. It means thinking and acting in terms of community. It also means combatting the structural causes of poverty, inequality, the lack of work, land and housing, the denial of social and labour rights. It means confronting the destructive effects of the empire of money… Solidarity, understood in its most profound meaning, is a way of making history, and this is what popular movements are doing” (FT 116).

Can we use the COVID disaster to do more than engage in spontaneous generosity, vital as that is? Can we use it also to look at the structures, the vested interests, the greed and the corruption that keep so many people in poverty and which will render them once again vulnerable when the next pandemic comes along?

| Dates To Remember |

|

April 1 – Holy Thursday; 2 – Good Friday; World Autism Awareness Day; 3 – Holy Saturday/Easter Vigil; 4 – Easter Sunday; International Day for Mine Awareness and Assistance in Mine Action; 6 – International Day of Sport for Development and Peace; 7 – International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda; World Health Day; 11 – Divine Mercy Sunday; 21 – World Creativity and Innovation Day; 22 – International Mother Earth Day; 25 – World Malaria Day; 28 – World Day for Safety and Health at Work; 30 – Our Lady, Mother of Africa May 1 – St Joseph the worker; Workers Day; 3 – World Press Freedom Day; 8 – Remembrance and Reconciliation for the Victims of the Second World War; 15 – International Day of Families; 16 – Ascension of the Lord; World Communications Day; 20 – World Bee Day; 22 – International Day for Biological Diversity; 23 – Pentecost Sunday; 24 – Closure of Special Laudato Si’ Anniversary Year; 29 – International Day of UN Peacekeepers; 30 – World No-Tobacco Day |