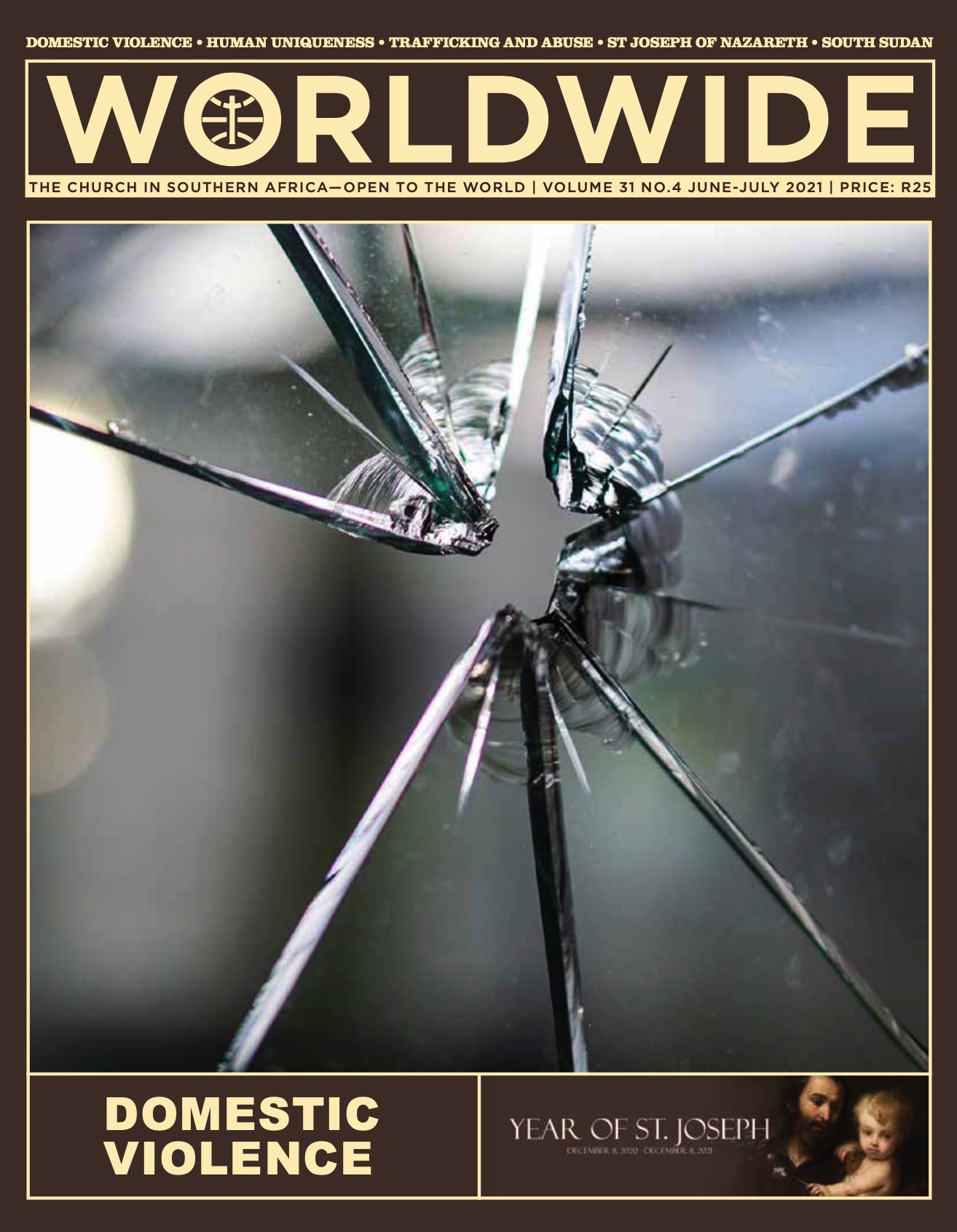

Domestic Violence

The shattered glass represents the broken lives and dreams caused by domestic violence. abuses in families are absolutely contrary to God’s plan of mutual care and fraternity for humanity. domestic violence, inflicted especially upon women and children, is a horrendous scourge. To eradicate it we need to foster the education on values of love, equality, respect and dialogue, in society. The alleviation of poverty, protection of the vulnerable and law enforcement will give the victims the courage to speak out and unveil this atrocious crime.

Frontiers • Vocation

MISSION TOWARDS RECONCILIATION IN SOUTH SUDAN

BY gregor schmidt mccj | Comboni Missionary in South Sudan

FATHER GREGOR Schmidt (born in Berlin in 1973) has been working among the pastoralists of South Sudan for the past 12 years. Born of a German father and a Korean mother, he met the Comboni Missionaries in Peru, during a volunteering service. After his theological formation, he was sent among the Mundari group with whom he stayed for three years and for the last nine he has been with the Nuer.

During this period in South Sudan, Fr Gregor has witnessed the different phases of state-building and the disintegration of the country: the interim period, that started in 2005 with its Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), the first free elections in 2010, the referendum on independence, won with 99% of approval, the declaration of independence in 2011, and the beginning of the civil war at the end of 2013.

THE ARRIVAL OF THE GOSPEL

The prophet Isaiah mentions the peoples of Sudan: “Offerings will be brought to Yahweh on behalf of the tall and bronzed nation, a people feared near and far, a nation mighty and conquering, whose land the rivers divide” (Is 18: 7). The “rivers” are the Nile with its numerous tributaries that cut through the territory. Isaiah foresaw the time when these peoples would bring gifts to the Lord in Zion. It did not happen in his lifetime, but rather in New Testament times. The African, in Acts 8, baptized by Deacon Philip, was the first Sudanese Christian from the Meroe Empire of Queen Candace. The man himself, whose conversion happened even before the Gospel reached Europe, left no historical traces.

From the third century, contacts were documented between Egyptian monks and Christians of Sudan (Nubians) and, from the sixth century, all their royal dynasties were Christian. There was a long period in which Christianity flourished in Sudan until the 15th century.

CHRISTIANITY AND ISLAM

However, the memory of the Christian faith disappeared completely under the influence of Islam and was only made known—for the second time—by St Daniel Comboni almost 400 years later. Only at the end of the 20th century, the Nuer, the Nilotic people with whom I live, became Christians in large numbers. In colonial times, there were only sporadic conversions.

During the second half of the 20th century, the Nuer were displaced due to the Sudanese Civil War. Expelled from their homeland, some became Christians as refugees when they met Catholic and Protestant missionaries in Khartoum and Ethiopia. During the liberation struggle against their Islamic government—which discriminated against black people and enslaved and killed countless non-Muslims— they discovered God as the Holy One who hears the cry of His suffering people, just as He heard the enslaved Israelites in Egypt.

The Gospel spread among the Nuer like wildfire during the 1980s and 1990s when returning converts shared their new faith with their families in the villages. The vision of Isaiah that the “people tall and bronzed” of the Nile would worship God, became true with them. Today, there are hundreds of thousands of Nuer Christians: mainly Presbyterians, Catholics and Episcopalians (Anglicans). A Catholic catechist reported that he baptized more than 20 000 converts during his time on duty. This shows that the local Church in its beginnings has been essentially a lay movement, without clergy.

MISSION IN FANGAK

The Comboni Missionaries were invited in 1998 by the Bishop of the Diocese of Malakal to accompany Catholics who lived scattered in the villages of the Fangak region in the South, the wetlands and marshes of the Nile.

The young Christian community, whose first generation of believers are still alive, is extremely hospitable and generous. We missionaries visit people regularly in their villages. We walk on foot to distant chapels, up to four days away from the parish centre, since there are no roads. The parish territory is huge, about five times the size of the Greater London area. Paths that are not used disappear within a few weeks in the constantly growing vegetation. During half of the year, the waters of the Nile and the rains flood the region, becoming flat as a disk. There are no hills except termite hills. On our hikes, we cross waters that reach up to our necks. Tropical diseases are part of everyday life and safe drinking water is rare.

The basic food of the Nuer consists of sorghum (millet) with milk or fish. They plant and harvest with hand tools, as the ox plough has not yet been introduced in this region. Furthermore, there is no telephone/mobile phone network, no postal service, no power grid—we depend on solar power—and no local radio station; only shortwave radio works to receive BBC and Vox of America. In recent years, some humanitarian organizations have set up satellite dishes for internet communication. If it makes sense to speak of the “ends of the world” on this planet, I think that the marshes of the Nile are a good contender for it. I am grateful to testify that the Triune God is worshipped in one of the most remote places on earth.

TRAINING OF RELIGIOUS LEADERS

The main task of the missionaries is to train prayer leaders and teachers of faith (catechists) in their chapels. Our parishioners have a strong, sincere faith in Jesus as their Redeemer, but little Christian education. We offer the catechumenate for adults who ask to become Christians. About half of Fangak County’s population is now baptized. There are many followers of traditional religion who are attracted to Jesus Christ. We offer education programmes in Nuer and English since more than 95% of the population in this part of South Sudan are illiterate due to their isolation (nationally, the illiteracy rate is at about 75%). We have been operating a primary school at the parish centre since 2014. So far, around 250 grade eight students have graduated with a certificate. It is a tiny seed, but significant, considering that less than 1% of the county’s population have obtained a primary school certificate, a document as prestigious as a doctorate title in developed countries.

Due to the recent civil war, reconciliation between various ethnic groups has become an important task, not only for us, but for all the churches in South Sudan.

WORK OF RECONCILIATION

The South Sudanese Catholic Bishops’ Conference has been having difficulty in reaching and gaining influence among warring parties since many bishoprics have been vacant. In addition, ethnic belonging is still a strong aspect of the identity of Catholics and of Christians in general, as is among church leaders. In this difficult tension between cultural and faith identity, the ecumenical South Sudan Council of Churches, of which the Catholic Church is a founding member, prepared a path towards national reconciliation.

In our parish, the war reached only the fringes of Fangak County, with the exception of its capital, New Fangak. Other areas have not been directly affected by battles or displacement. This has been the case, due to the isolation of the area, created by the Nile swamps, and thus lacking road connections. In our diocese, in whose territory much of the fighting and destruction took place, our parish is the only one that has not had to be closed in all these years. In all other parishes of Malakal Diocese, the work was stopped for several years. Still, every Nuer family of our parish has lost relatives in the war. Because the enemy breathes down their necks, but is still reassuringly far away, our work of reconciliation looks different from a parish with mixed hostile groups.

I am working on the side of the ‘losers’. Although the Nuer of my region wish to get rid of the current government, it is a blessing from the point of view of the Gospel to belong to the marginalized (cf. Lk 1: 51–53). In order not to be misunderstood, I add that those South Sudanese controlling the government are not worse people than others, but simply, they have more opportunities because they possess better weapons and can count on Uganda’s military aid. Apart from the first year of fighting, when the opposition had some victories and committed terrible crimes among the Dinka, the war has mainly taken place on territory where people who support the opposition parties traditionally live, and is reaching the Dinka homelands only peripherally. In addition to genocide of minorities and ethnic cleansing in the Greater Equatoria Region, there is also expulsion and confiscation of land by the government, which settles its own loyal people there. Even though this has not yet taken place in our parish area, it is an enormous challenge to preach the love of enemies in such a context.

Some people ask why South Sudanese Christians don’t just follow the word of Jesus and forgive their enemies. That suggestion is easily expressed for those who do not have a real enemy seeking to kill them or destroy their livelihoods. As a foreigner in South Sudan, my own life is not threatened by anybody. I do not superficially demand love of one’s enemy from Christians of my parish, as this would be to ask something that I do not have to implement myself. Instead, I have made the suffering of the Nuer my own suffering and make no demands. We pray for the dead and bless the wounded who are taken to our hospital ward.

RECONCILIATORY SIGNS

On certain occasions, our Nuer Catholics pray at Mass in the language of the Dinka as a sign for national reconciliation. At the local level of clan conflict, traditional reconciliation goes hand in hand with Christian prayer (insofar as the clans are Christian). Our active parishioners are noticeably less violent than the average Nuer. The ecclesial life is like a shelter where a new, peaceful lifestyle is maintained. The Catholic Church is known and loved for the fact that differences of opinion are settled without violence.

In contrast to traditional festivals and gatherings, weapons and alcohol are not allowed on church grounds. Anyone interested in this ‘alternative lifestyle’ can join us. A traditional feast often runs the risk of ending in bloodshed because youth (men) injure or kill each other. Either a previous attack needs to be revenged or a new dispute is started under the influence of alcohol.

Furthermore, in our sermons and conversations, we shape the idea of inviolable human dignity because every person is an image of God. The word dignity cannot be adequately translated into Nuer. As an illustration, we explain that everyone must respect other persons deeply, even if they are women or strangers of another tribe. The stories of Jesus in the Gospels help to underline that message. In South Sudan, there is no secular society. Therefore, international peace programmes, which always appeal to reason and emphasize human rights, have little effect on the ground because they do not understand the dynamics of people’s ethnic and religious identities, or they negate them. As a missionary, I make the Gospel—which presents God as a merciful Father—known to my listeners. A disciple of Jesus is called to imitate the Father and love the neighbour, even the enemy (cf. Eph 5: 1, 2; Lk 6: 27–36). It is about a change of mentality so that it is no longer the ethnicity or the clan which defines whom one can or not trust. The Gospel and the Bible clearly show what constitutes a just, honest person. This should be the benchmark for building a just and peaceful society.

A peaceful and conciliatory attitude is the strength of the Church and the missionaries. We live with ‘our’ people and suffer with them. Jesus Christ changed and converted people by loving concretely and making Himself the servant of all. We missionaries strive to learn language and culture, and walk their paths both literally and figuratively. People honour this, and they are ready to open themselves to the perspective of the Gospel because we have opened ourselves to their perspective. Patience is needed. Jesus explains that the Kingdom of God grows like a tree, slowly but steadily.

BACKGROUND OF SOUTH SUDAN

South Sudan is a multi-ethnic society with more than 60 peoples/languages. About three-quarters of the population are semi-nomadic shepherds (pastoralists). The country is one of the least developed/urbanized regions in Africa and has been suffering the longest war in Africa. Since 1955, the population has been experiencing fighting, with only two longer periods of calm (1972–1983 and 2005–2013), which has traumatized four generations of people. The liberation struggle in former Sudan against the rulers in Khartoum had cost more than two million lives. The current civil war so far has taken approximately 400 000 lives. Since the signing of the last peace agreement in September 2018, the situation has stabilized somewhat. For most of the time during the civil war since 2014, the Fund for Peace has placed South Sudan in first place on its Fragile States Index. Source: wikipedia.org/wiki/Fragile_States_Index.