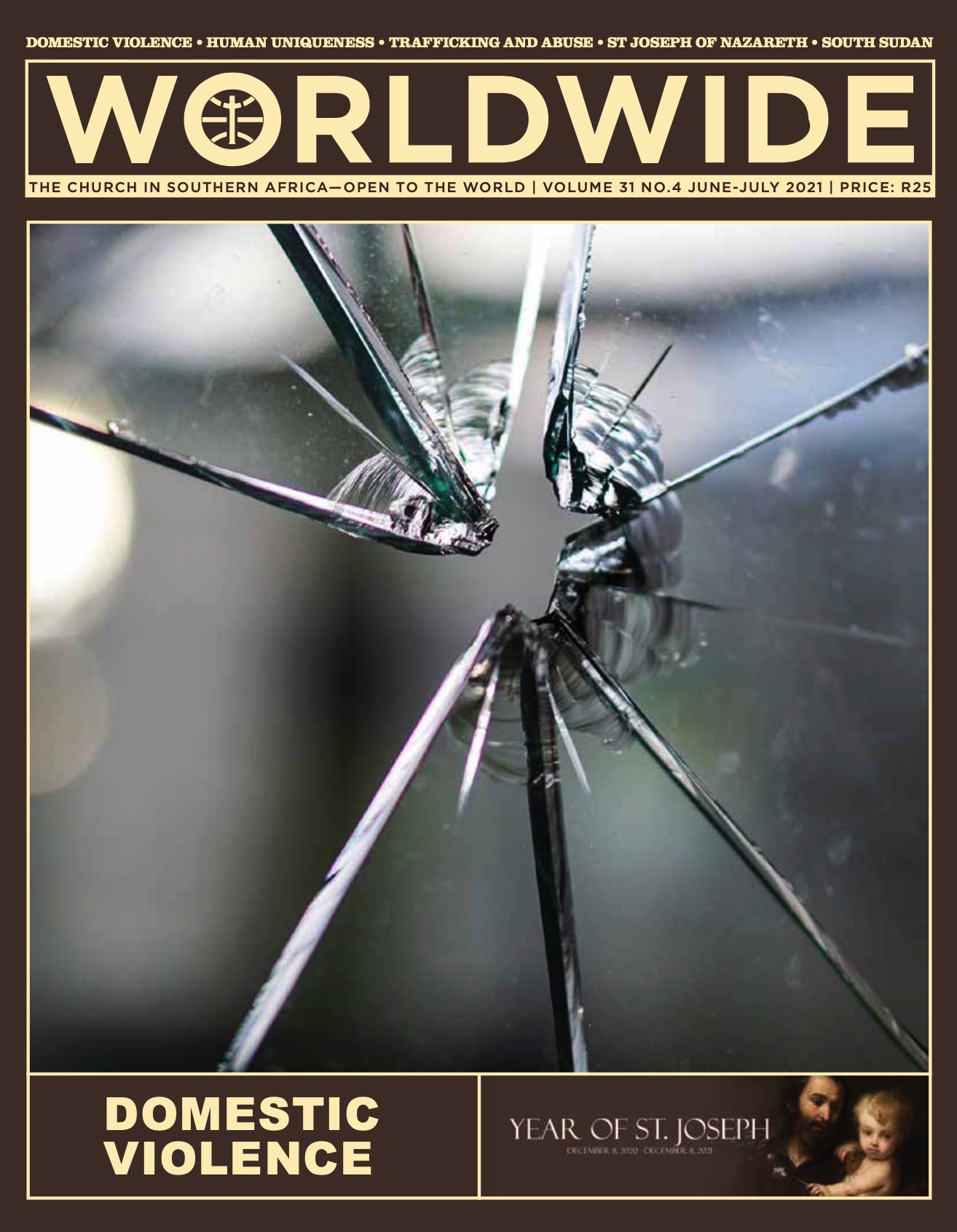

Domestic Violence

The shattered glass represents the broken lives and dreams caused by domestic violence. abuses in families are absolutely contrary to God’s plan of mutual care and fraternity for humanity. domestic violence, inflicted especially upon women and children, is a horrendous scourge. To eradicate it we need to foster the education on values of love, equality, respect and dialogue, in society. The alleviation of poverty, protection of the vulnerable and law enforcement will give the victims the courage to speak out and unveil this atrocious crime.

SPECIAL REPORT • PATRIARCHY

Patriarchy and the Church

Gender-based violence (GBV) is overwhelmingly a sign of a patriarchal mentality, an expression of a culture where male domination is considered normal. While the Church rightly condemns GBV, I shall contend that the Church endorses a form of patriarchy that creates a culture in which the mentality that leads to such violence can thrive. This need not be so—the Church has the inner resources through critical re-examination of Scripture and Tradition to clean up its act

BY FR ANTHONY EGAN SJ | PRETORIA

DEFINING A FEW TERMS

LET ME start by defining a few terms.

First, gender-based violence (GBV) is “violence that is directed at an individual based on his or her biological sex or gender identity. It includes physical, sexual, verbal, emotional, and psychological abuse, threats, coercion, and economic or educational deprivation, whether occurring in public or private life” (Ott 2017). These include (predominantly) violence against women and girls, violence against LGBTI people, intimate partner violence, domestic violence, sexual violence, and indirect (or structural) violence.

Second, what is patriarchy? Patriarchy is a system where men hold primary power and predominate in roles of political leadership, moral authority, social privilege and control of property (Lerner 1986; Walby 1990). Note the qualifiers: it does not mean that women are totally excluded, just that power, authority and privilege are predominantly in male hands and that the culture privileges men. Sylvia Walby notes further certain features: women have less representation (hence power) in the state; women do most of household work; they are paid less in work; their sexuality is treated with suspicion; women are seen in culture through a ‘male gaze’; and (which brings us back to GBV) they are more prone to being abused (Walby 1990).

PATRIARCHY IN THE CHURCH

From the above definitions, I think it is clear that the Catholic Church is patriarchal (probably all churches in fact), even if it roundly condemns GBV, though some might argue that as a patriarchal structure it may be guilty at least of indirect/structural violence.

I am not going to go into too many details to suggest how the Church’s practices reflect all too well the characteristics of patriarchy, Walby notes. There is a male clerical ruling caste—and it is not helpful to protest that we (for I am part of the caste) don’t rule, but lead through service. However we phrase it, and however much in recent times steps have been made to include women in some aspects of leadership, we must be brutally honest and admit it.

Moreover, the official perception of women in the Church and society comes through male lenses. Though, creditably, the official Catholic line has rejected the medieval notion of women as ‘defective males’ (based on the outdated, dare I say defective, science of Aristotle) the new theological anthropology of complementarity (of, for example, Pope John Paul II 1988) remains problematic. Complementarity, broadly speaking, assumes the essential difference between men and women (in society and Church) and argues that their roles complement each other. Apart from the fact that it seems to deny the scientific and social complexity of gender itself (Butler 1990), while it proclaims that women are completely equal to men in the sight of God, it tends to take dominant gender roles as a given. Some might call it a ‘separate but equal’ position. It certainly does not embrace changing power structures and roles within the Church significantly.

Also noticeable is the Church’s deep unease with any new ideas about gender, ideas rooted in scientific research, summed up in regular condemnations of what is described as ‘gender ideology’. Even a fairly progressive pope like Francis seems stuck in this mentality (Case 2016: 169).

Why is this happening? Behind it, I think, is a way of thinking that the practice of the Church is the will of God articulated by tradition and confirmed by Scripture. Quite simply, it cannot change. But is that so?

SCRIPTURE AND TRADITION THROUGH REASON AND EXPERIENCE

One way out of this impasse is to read Scripture and Tradition through the lenses of reason and experience. My starting point draws on all four sources for moral theology to address a moral problem (and patriarchy is a moral question). By reason, I mean philosophical argument and the use of critical methods. By experience, I understand engagement with historically based accounts of lives undergoing patriarchy and its effects.

Let us start with Scripture, which I understand as the primary layer recording the religious experience of the community of Jews who understood Jesus as the Messiah. (This naturally includes the Hebrew Bible which was the theological lens through which they understood Jesus). The first thing we need to say, apart from the fact that space prevents me from close readings of specific biblical texts, is that the Bible is at best ambivalent about women, at worst, it endorses patriarchal culture. Although some fine feminist biblical scholars have tried to retrieve a more ‘women-friendly’ reading of at least some of the texts (Schussler Fiorenza 1993, 1994), some even suggesting that the earliest stratum of Christianity constituted a ‘discipleship of equals’ (Schussler Fiorenza 1983), a blunt assessment must state that the Bible in general reflects the patriarchal culture in which it was composed.

Patriarchy is a product of a taken for granted worldview in which the authors lived, worked and tried to find the presence of God.

The culture itself was a product of history; 12 000 years ago, “[w]ith the advent of agriculture and homesteading, people began settling down. They acquired resources to defend, and power shifted to the physically stronger males. Fathers, sons, uncles and grandfathers began living near each other, property was passed down the male line, and female autonomy was eroded. As a result, the argument goes, patriarchy emerged” (Ananthaswamy & Douglas 2018). Before that, during the hunter-gatherer stage of human evolution, things were more equal. The authors above describe the archeological and paleontological evidence for this.

Applying reason to Scripture we can see that the textual basis for patriarchy is a product of a taken for granted worldview in which the authors lived, worked and tried to find the presence of God. However, you may ask, what of the divine inspiration of Scripture? We must distinguish here between the idea of divine dictation—God telling Moses or Mark or Luke “take this down”, which is not how we understand the origins of Scripture—and inspiration. The authors of the Bible were inspired to write down within their historically and culturally (as well as scientifically) limited understanding how they experienced God in their lives, whether as a nation in exile or as a tiny Jewish minority who called Jesus the Messiah.

SEARCH FOR KNOWLEDGE

We have to engage in a critical epistemology, a search for knowledge, to interpret biblical texts; we must also engage in a process of sifting fact from opinion, knowing that some ‘facts’ may only have been true because the authors did not know what we now know. We must also distinguish between practices taken for granted (i.e. culture) then, and what we now take to be acceptable.

Christian theological thinking was limited by the best available contemporary scientific knowledge

The same critical principles apply to our examination of Christian Tradition. We may not like to think it, but many of our Christian practices (even some beliefs) are as much, if not more so, the results of adoption and adaptation to the cultures in which Christianity flourished. We can see this in the language of absolute kingship of Christ and the reign of God: to understand the truth of God’s sovereignty, Christian scholars literally imagined God as king above all human kings. Kingship was all they knew. Similarly, some doctrines openly used the medieval ideas of honour and duty—peasant to feudal lord, feudal lord to king—to understand Christ’s role in atonement for human sin. Today we must seek the truth behind the language.

Similarly, Christian theological thinking was limited by the best available contemporary scientific knowledge. Within such knowledge, like Aristotle’s biology, the Church had to make social and moral judgments which may have seemed to work at the time. The problem arose, and arises, when new scientific insights challenged views that were taken for granted, even considered unchanging and unchangeable Tradition.

WHAT ABOUT PATRIARCHY?

Based on what I’ve said above, it seems clear that patriarchy is a historical-cultural product that has been grafted onto the Christian tradition. It is a human construct. There is no evidence that it is divinely willed. Scrapping patriarchy in no ways compromises any essential elements of Christian faith. In our time, it has come under fire because it fails to live up to the demands of justice—a notion integral to the Christian understanding of God even when the cultural accretions attached to it in Scripture and Tradition are scraped away. Insofar as it is rooted in our understanding of gender and gender roles, it is also no longer scientifically viable based on our best available knowledge.

Patriarchy is also a source of violence, because it rationalises male violence against women in many forms, not least as a form of institutional violence. In our time, in the age of #MeToo and other movements, it is no longer being tolerated, no longer being allowed to be swept under the carpet.

Of course, patriarchy is not going to die easily. The rise of GBV, particularly in a country like South Africa (Safer Spaces 2021), might even be seen as a symptom of ‘patriarchy’s last stand’, a desperate attempt to hold onto the status quo.

CHURCH’S STAND

Where does the Church stand? Commendably the Church opposes GBV, but sadly still holds onto views on women and gender that, ironically, seem to support patriarchal assumptions from which GBV flows. To be ethically consistent and genuinely address this problem within the Church (and not simply to silence or ignore the troublemakers who raise these questions) I believe we need to rethink a lot of presuppositions. Change is painful. People prefer to avoid pain.

However, the cost of avoiding such pain could be much worse. Let me conclude with a story. In November 1971, after preaching a powerful sermon, feminist theologian Mary Daly (1992) walked out of Harvard Memorial Church—and out of the Christian Church—in protest against what she believed was Christianity’s ‘irredeemably’ patriarchal nature. Many, most, feminist theologians chose to stay within the church and struggle for the end of patriarchy. Today, even women who would not normally call themselves feminists are getting sick of GBV and patriarchy. Failure to respond to the crisis might generate a mass exodus of women from the Church, not just the departure of a few theologians.