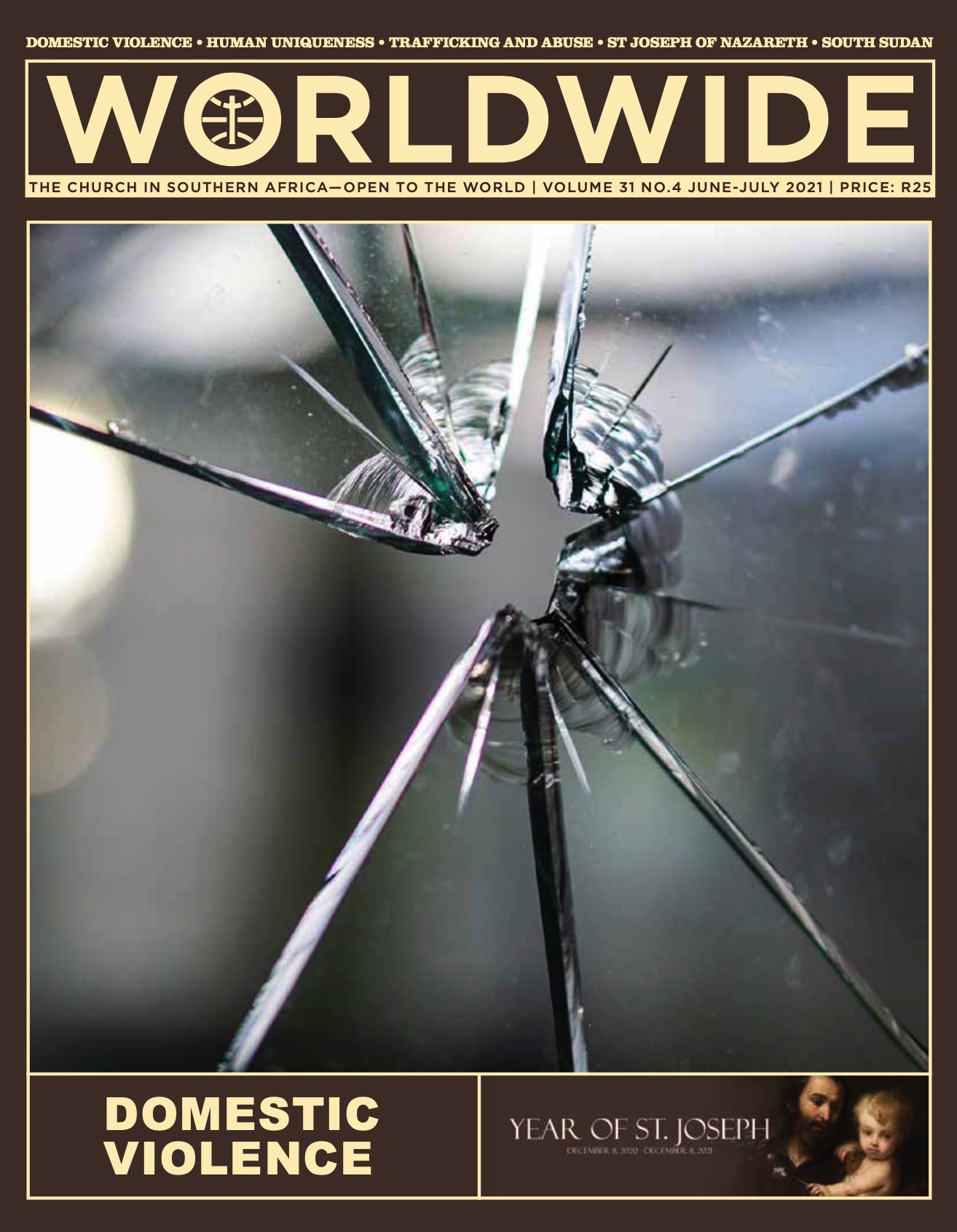

Domestic Violence

The shattered glass represents the broken lives and dreams caused by domestic violence. abuses in families are absolutely contrary to God’s plan of mutual care and fraternity for humanity. domestic violence, inflicted especially upon women and children, is a horrendous scourge. To eradicate it we need to foster the education on values of love, equality, respect and dialogue, in society. The alleviation of poverty, protection of the vulnerable and law enforcement will give the victims the courage to speak out and unveil this atrocious crime.

INSIGHTS • DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT

What Can The Law Do About Domestic Violence?

BY MIKE POTHIER | PROGRAMME MANAGER, SACBC PARLIAMENTARY LIAISON OFFICE

GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE, domestic violence (DV), and violence against children have often been focused on in Parliament. Every year, during the 16 Days of Activism for No Violence against Women and Children Campaign in November, a debate is held in the National Assembly, in which all parties condemn DV and call upon the government to do more to combat it.

Sometimes, unfortunately, these speeches become repetitive. MPs say the same things that they said the previous year, and the same things that their colleagues from other parties say, but the reality outside Parliament doesn’t seem to change much. Certainly, there is no indication at all that the men—and we know that it is almost always men—who perpetrate DV, pay any attention to what well-meaning politicians say on the subject.

THE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT

What, then, about the things that MPs do—the laws they make? In 1998 the Domestic Violence Act was passed. It was an innovative piece of legislation in a number of ways. For example, it employed a very wide definition of DV, going beyond the obvious physical and sexual violence to include economic, emotional, verbal and psychological abuse; intimidation and harassment. This was an important acknowledgement that violence, especially in the home, can be a far more subtle and hidden matter than is usually supposed.

The Act also placed a positive duty on the police to assist complainants to lay charges, and to inform them about their legal options. This was an attempt to overcome one of the most notorious problems faced by victims of DV—the fact that the police often fail to take it seriously. Many police officers tend to see it as a private matter between husband and wife, and not really a crime at all.

The provision for a protection order to be granted via a fairly straightforward and accessible process, was another useful innovation. In effect, a victim of DV, or someone acting on their behalf, could obtain an interdict against the alleged perpetrator quickly, thereby ensuring as far as possible that there would be a physical separation between the two until such time as the matter came to trial or was otherwise resolved.

How effective has the Domestic Violence Act been? Clearly, it has not brought about the kind of decline in the problem that was hoped for. However, we should also recognise that, without this law, things might be even worse than they are. The queues of people seeking protection orders at magistrate’s courts, especially after a weekend, are long, which indicates on the one hand that this kind of violence remains a major issue, but on the other, more positively, that victims see the protection order as something worthwhile.

Over the years since 1998, the Act has been amended a few times to try to make it more effective, and a further set of amendments is currently before Parliament. The definition of DV is being extended even further, to include ‘elder abuse’ and ‘spiritual abuse’ and there are also improvements to the procedure for obtaining a protection order.

However, the new amendments also contain worrying provisions regarding mandatory reporting. It is one thing to require people, by law, to report DV when the victim is unable to do so—if he or she is a child, for example, or mentally disabled, but when the victim is an adult, and able to decide for herself whether or not to report it, then to make it compulsory is to rob the victim of her dignity by treating her, in effect, like a child.

That these amendments have been deemed necessary shows that the original Act has not had the desired effect. DV is a deep-rooted social problem, with links to patriarchy, certain cultural and religious tenets, socio-economic stresses, and numerous other causative factors. Unfortunately, while it is an uncomfortable fact that laws can only do so much when it comes to addressing such problems, governments always tend to reach for the statute book in such cases. For one thing, it makes it seem like they are doing something urgent and forthright. For another, it means that they don’t have to tackle the much harder task of bringing about the kind of social, cultural and other transformations that are needed to deal with this kind of problem.

Even if we acknowledge that, over the years, our lawmakers have taken the issue seriously, and have tried to intervene legislatively, we must surely accept that the answer to the problem of DV does not lie in the law. It lies, instead, in changing the way men relate to women and to children; and in righting the many wrong signals that society sends out about what it means to be ‘a man’ —powerful, assertive, aggressive, and in charge; rather than loving, kind, gentle and in service to those around him, especially his family. To bring about these changes will require much more than simply passing a law or making a speech in Parliament.