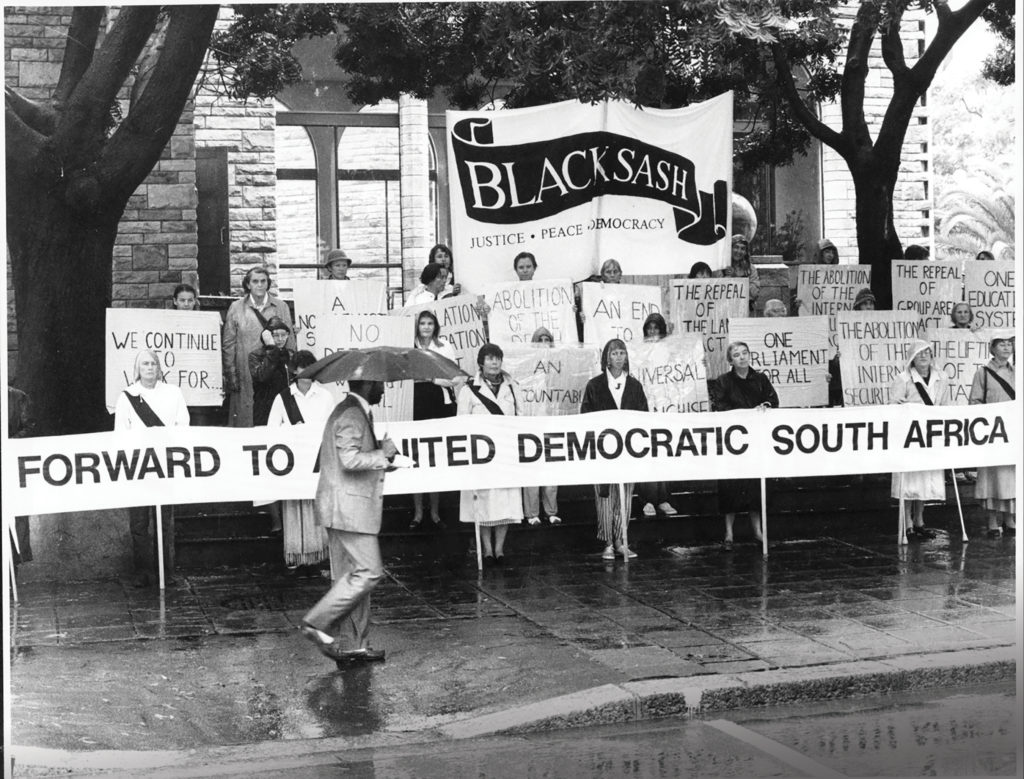

SPECIAL REPORT • BLACK SASH

A Story Of Struggle for Justice In South Africa

A courageous group of women, initially mostly whites, fought under the apartheid regime

for human rights of the disenfranchised black majority. Now intercultural, they continue

the fight to guarantee the access to social grants for dispossessed people.

It follows the account by a longstanding member of the group

BY Mary Burton | Black Sash Patron, Randburg

IN 1948 the National Party of South Africa won a majority in Parliament for the first time and swiftly embarked on the process of putting into law its policies of racial segregation which separated people according to racial classification, calling this process apartheid.

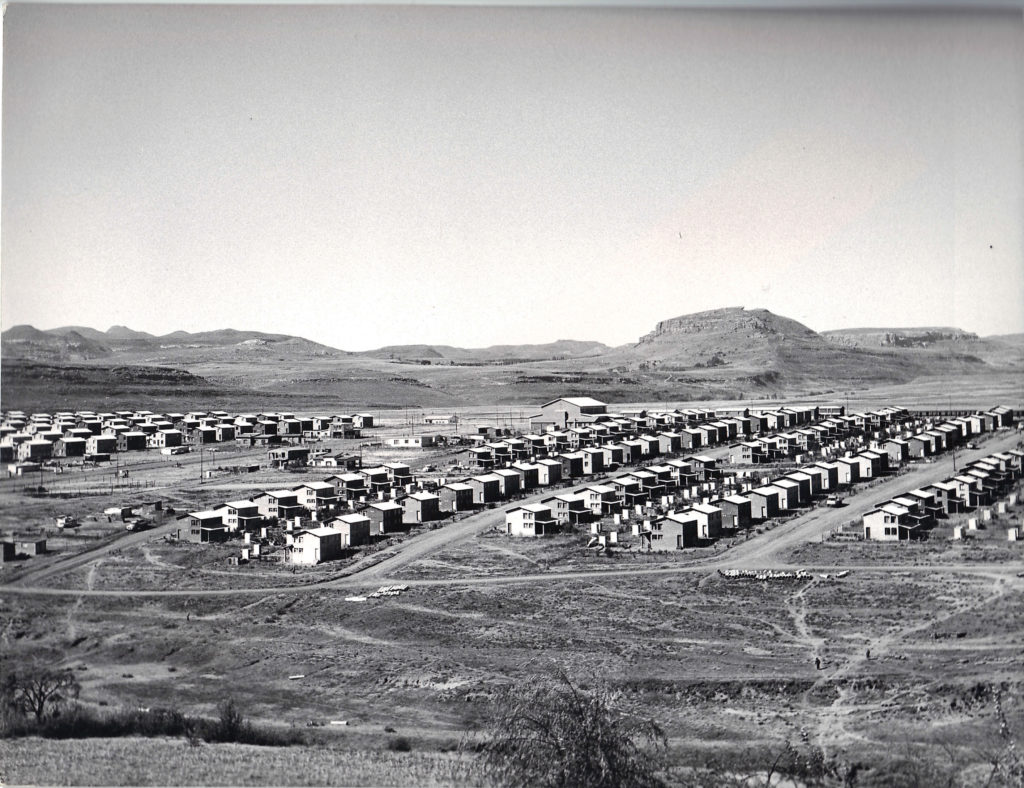

They passed legislation which dealt with every aspect of life in South Africa. This included the Population Registration Act (1950) which defined every citizen according to ascribed race. The Group Areas Act (1950) defined separate areas on a racial basis and millions of people were forced to move, losing homes and business properties. For example, families classified ‘coloured’ or ‘Indian’ who had lived in areas now allocated to white people, lost not only their homes but their shops or offices. The provision of education, health, welfare and other services was also separately allocated for the defined population groups.

Differentiation and inequality had existed since the beginnings of colonialism, but it was now to be further entrenched and enforced. One of the means used to accomplish this was to remove the last existing rights to vote on the common roll which were still held by specific groups of ‘black’ and ‘coloured’ voters. The Constitution of 1910 had provided some protection for these rights, which required a two-thirds majority in Parliament to be altered. The National Party did not hold such a majority, and at first it failed to pass legislation for the Separate Registration of Voters Bill. In the end it resorted to enlarging the number of members of the Senate, which gave it the necessary majority and the law was pushed through in 1956.

The beginnings

Many white citizens who themselves still had the right to vote were outraged at this injustice, and there were widespread protests. Among them was a group of women who banded together in May 1955 to form a body which they named the Women’s Defence of the Constitution League. First in Johannesburg, then throughout the country, they marched in the cities, they held protest demonstrations in small and large towns, they drew up petitions and obtained thousands of signatures, they held overnight vigils and went to Pretoria to deliver their demands to the government. They wore black sashes as a symbol of mourning for the betrayal of an agreement guaranteed by the Constitution. They became known as the Black Sash and adopted the name at their first formal national meeting.

They protested against the removal of the rights of coloured voters, and against the way this law had undermined the Constitution. As white women privileged to be able to vote, they believed it was their duty to act, and at first, they trusted that appeals and protests would influence the public and the government to prevent this entrenchment of apartheid. There were thousands of them (estimated at between 10 000 and 20 000 although there are no accurate records from that time of frenetic activity), but in the end it was not enough. One of the posters held in their protests said “Legal now, but immoral forever”.

The Black Sash and the other organisations within the predominantly white community had to recognise that their protests had failed. At the same time, the organisations all around the country which represented the black population who had lost the little electoral power they had, were gathering strength for ongoing opposition. The African National Congress had proclaimed the Freedom Charter in 1955 and other organisations were gathering strength.

Pass books

African black men had been subjected for many years to control over their freedom of movement in what were considered to be ‘white’ areas. The terms of the Natives (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act of 1945, as amended in 1952, laid down the latest regulations: no black man could remain in a prescribed area for more than 72 hours unless he could provide proof that he had lived there since birth, or that he had been working continuously in that area for a specified period, or that other conditions had been fulfilled. The ‘proof’ was contained in a document which came to be known as the pass book, and had to be carried on his person at all times.

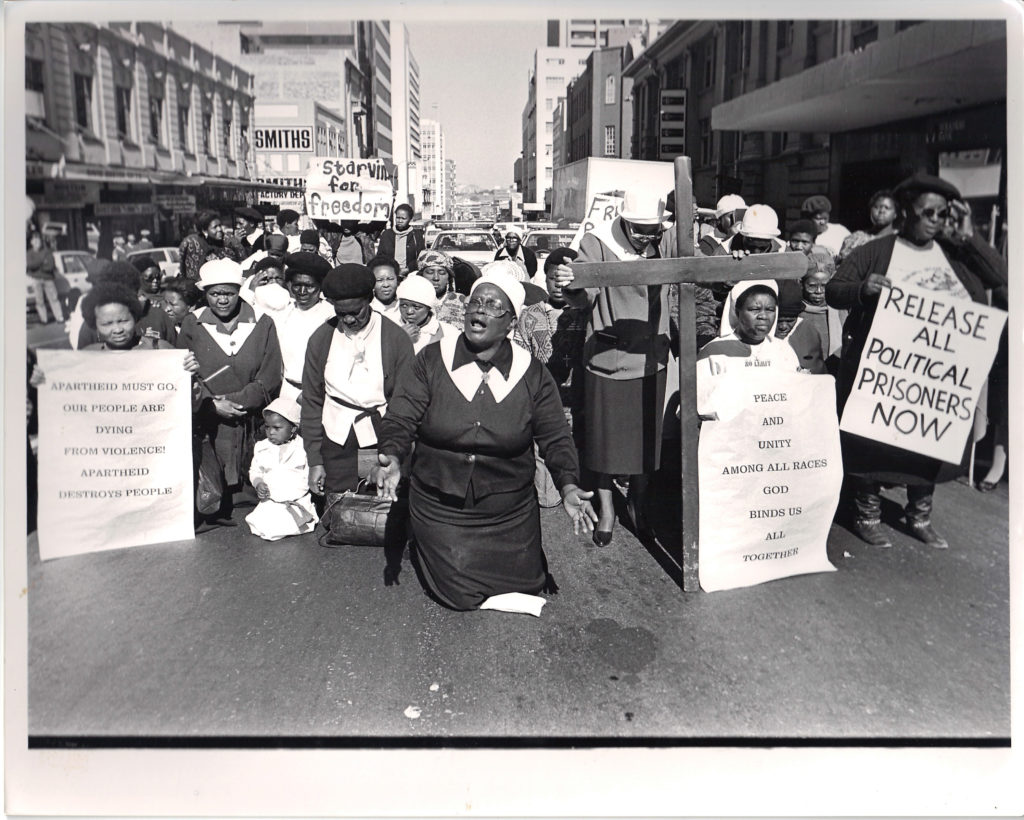

Then these requirements were to be imposed on black women too. The Federation of South African Women (FSAW) was mobilising its membership as these hated pass laws were being extended to black women. Months of preparation culminated in a spectacular gathering of thousands of women who had travelled from all over the country to Pretoria for a march and demonstration at the government’s Union Buildings on 9 August 1956—now embedded in South African history as National Women’s Day.

Uniting forces

FSAW was composed of women of all racial groups, and some of the white women in it were also members of the Black Sash, although probably very few. At that time the Black Sash was still identified as an organisation of white women.

The threat of the pass laws would begin to change that. In Johannesburg when black women were arrested for resisting the pass laws, Black Sash members supported them with practical and legal help. In March 1958, twenty African women were arrested in Cape Town, some of them with young babies, for failing to produce such permits, and spent several days in jail because they had no money to pay bail. Black Sash members were prompted to act.

The majority of Black Sash women had until then known too little about the pass laws. Now the story of these women aroused their concern, and their first step was to establish a Bail Fund. Then, the process of having to administer it made them more acutely aware of the suffering caused by these laws, and drew them into establishing an Advice Office to try and help.

Advocacy

Run by volunteers with the assistance of interpreters, the Advice Office administered the Bail Fund, but did much more: it listened to the dozens of people who came forward to recount their struggles with the pass laws, it monitored the special pass courts that were set up, it helped to find lawyers who would represent people arrested in terms of those laws. Over the next few years, the Black Sash established advice offices in other cities too, and its knowledge grew about this law and its terrible effects.

Sheena Duncan, long-term advice office worker and leader of the Black Sash wrote: “An advice office is a place where people are given information about various laws and the structures of administration in their area. To transfer information is to transfer power. An advice office is a place where people learn how to solve their own problems”.

The members of the Black Sash themselves also learned in the advice offices about laws and administration, and acquired the confidence and experience to approach government officials, to write letters and newspaper articles, to try to alert the public about the injustice and suffering they witnessed, and to continue their protest activities on this and other infringements of the principles of justice, freedom and equality.

The initial support from thousands of signatories to the constitutional demands fell away, and numbers dwindled. Those who remained members took up a variety of issues, such as inequality in the provision of public services, and the gradual progression over the next decades in the entrenchment of apartheid laws. Black African people were to be deprived of their rights as South African citizens, being deemed to belong instead to homelands or Bantustans. Individuals and entire communities were forcibly removed from supposedly white areas in cities and rural areas.

Opposing oppression

Power and coercion were the weapons of the apartheid state, while the Black Sash opposition lay in its ability to monitor, record and publicise the impact of the unjust laws. It stood alongside those who suffered most, raised its voice in protest, helping to ensure that the country and the world should not remain ignorant of what was being done.

The next three decades brought increasing hardship for black South Africans, and gradually resistance grew, and was met with ever-tighter control. In 1976 widespread protests against unequal and inferior education demonstrated the coming of a new generation of opposition. All over the country protests and demands for justice brought thousands of people of many organisations into conflict with the authorities.

The government could no longer control the resistance movement in the country, and the war on its borders was impossible to sustain. In 1990 the negotiations to bring about a new system of government began, banned organisations were brought back into the constitutional discussions, and in 1994 the first fully democratic elections led to a new government with President Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela at its head.

What did this mean for the Black Sash, in addition to rejoicing at the outcome? In a new constitutional democracy, was there any place for a small, still mostly white group of women (membership had been open to all since 1963), whose many goals seemed to have been fulfilled? Filled with hopes for the future, what part could they play to make a contribution? Not protest, surely, but monitoring, advocacy, and experience in assisting people to overcome their problems in attaining social justice.

Democracy

In 1995, after many arguments and discussions, the decision was taken to close the Black Sash’s membership structure, and instead to carry its advice office work into the future under the leadership of a Board of Trustees responsible for the Black Sash Trust. In taking this step, the membership placed its legacy in the hands of the new structure and to the team of dedicated professional staff.

The trustees articulated the values which had in the preceding 40 years underpinned the work of the Black Sash, as guidelines for the new organisation. These were:

Justice

Dignity

Affirmation of women

Integrity

Nonviolence

Rigour

Independence and courage

Volunteers and civil society

In the early days of democracy, under a Constitution which provided for the rights of all people, the Black Sash worked with other civil society organisations to support the new government in developing new legislation and systems to make those rights real in the experience of the people. Yet poverty and inequality continued to affect the lives of millions of South Africans.

Social grants

Working in partnership with other civil society organisations, one of the major goals of the Black Sash was to address more vigorously the need for social security for those people who depended on government support to survive. Pensions for the elderly, child care grants, and disability grants, which had in the past been differentiated on a racially defined basis, became equal for all. Yet in many poor households, entire families were obliged to depend on those grants, since there was no other provision for those who were unemployed. In addition, there were many problems with the distribution of the grants, including inefficiency and corruption.

Together with community-based partners in different parts of the country, the small team of Black Sash staff undertook a process of monitoring and documenting the experiences of people trying to access their grants. Furthermore, the organisations campaigned for the provision of a basic income grant as the cornerstone of a comprehensive social protection system.

It became clear that irregular deductions were being made from the grants which people ought to have been receiving, and that the service provider which had been contracted by the government to distribute the grants had captured the system for its own benefit. The Black Sash and its partners embarked on a campaign demanding “Hands off our grants” (HOOG), which eventually led to a Constitutional Court challenge.

The story of this campaign, the dedication of the monitors and the courage of those who came forward to testify, the support of the indefatigable legal advisers, and the ultimate ruling of the Constitutional Court is told in a book soon to be published. The grants of about 18 million people are now being distributed through an integrated payment system and partnership between South African Social Security Agency and the South African Post Office.

Abject poverty and gross inequality continue, disgracefully, to stalk our country, and are now deepened by the COVID-19 pandemic. Millions of South Africans endure lives of such deprivation as to lead to despair and anger. Every possible effort must be made to remedy this situation.

Sustained by the values to which it is dedicated, the Black Sash, together with its partner organisations, continues to be an important building block towards that end.