RADAR

Source: EM -DA T Database

CLIMATE FINANCE ISN’T REACHING SOUTHERN AFRICA’S MOST VULNERABLE

The region desperately needs climate adaptation funds, but loses out to countries with strong institutional capacity and competitive markets

BY AIMÉE-NOËL MBIYOZO* & OTTILIA ANNA MAUNGANIDZE

DESPITE CONTRIBUTING less than other areas to climate change, Southern Africa is among the worst-affected regions globally and those bearing the brunt are the ones with the least resources to adapt.

The region’s governments have not prioritised adaptation measures such as early warning systems, climate-resilient infrastructure, dryland agriculture, mangrove protection, and resilient water sources.

Hard-hit weather region

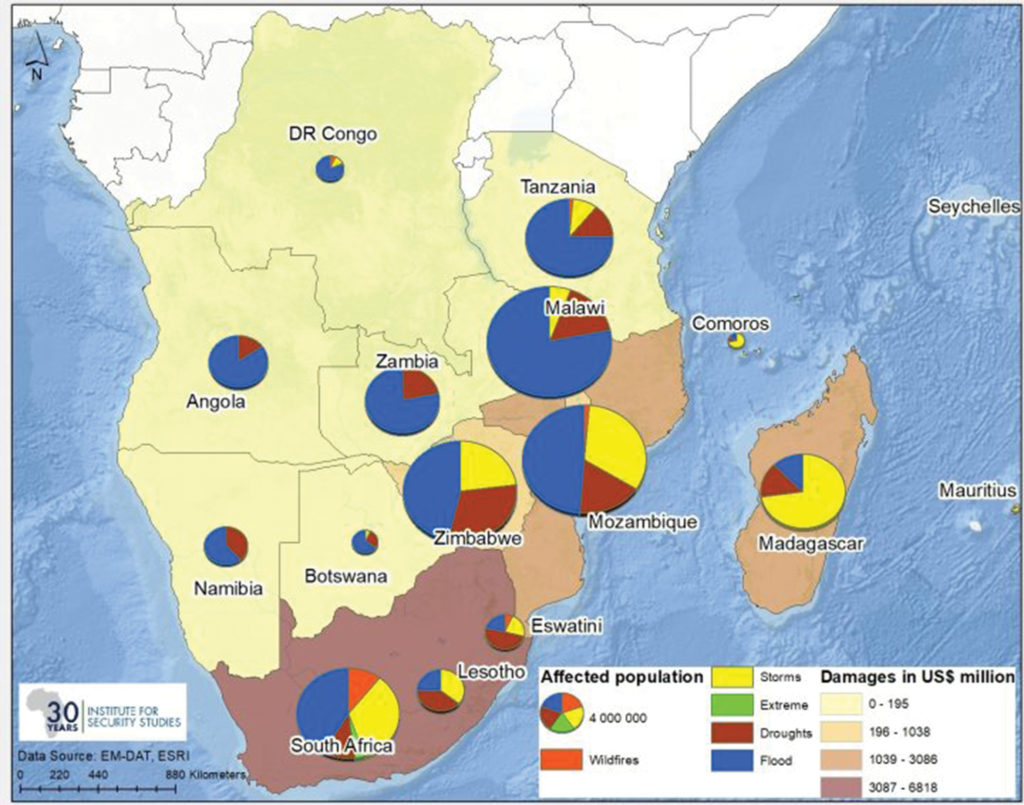

The World Food Programme has called southern Africa the ‘epitome’ of the link between climate and the water-energyfood nexus. The 16 countries of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) have recorded 36% of all weather-related disasters in Africa in the past four decades. These affected 177 million people, left 2.7 million homeless and inflicted damage in excess of $14 billion. Climate change will continue to increase the frequency, intensity, duration and locations of these slow and sudden-onset impacts.

Many communities in SADC depend on natural resources and their exposure to repeated and extreme hazards such as floods, droughts, storms and wildfiresrender them extremely vulnerable.

Tropical cyclones and severe thunderstorms tend to be the most destructive in southern Africa, posing the greatest threat to infrastructure and displacing the most people. Water is the region’s Achilles heel, with 90% of people requiring emergency assistance due to either too much or too little water. Since 1980, there have been 314 floods and 102 droughts in the region.

Malawi and Mozambique were most affected, with Zimbabwe and South Africa in third and four places respectively. Mauritius, Seychelles and Comoros had the fewest incidents. South Africa, Mozambique, Madagascar and Zimbabwe recorded the largest economic losses, whereas Lesotho, Tanzania and Seychelles recorded the least.

Globally, the least-developed countries have the fewest resources to plan, finance and implement adaptation measures, yet they incur the highest costs relative to their economies. In 2019, Cyclone Idai cost Zimbabwe $274 million and Mozambique $3 billion, 1.6% and 19.6% of their respective GDPs that year.

Climate funding is unequally distributed worldwide. Africa received only 26% of available financing between 2016 and 2019. Three-quarters of that were in the form of loans and other non-grant instruments that must be repaid. Most has been directed towards cutting emissions (mitigation), with adaptation assigned only 21% of global climate funding in 2018.

Meagre funds for adaptation

South Africa received the most multilateral climate financing on the continent and is placed sixth-highest internationally, but only 2% for adaptation, with the rest for mitigation. Zambia, Tanzania and Comoros received relatively high amounts of adaptation financing relative to their climate vulnerabilities, yet the sums are still inadequate to meet their needs.

While climate financiers regularly speak about prioritising the most vulnerable countries, vulnerability is not a key factor in determining where funds go Germanwatch’s Global Climate Risk Index 2021 ranked Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi the 1st, 2nd and 5th most affected countries in the world in 2019. Yet, they were placed 32nd, 108th and 75th respectively in climate financing received.

Many countries with the highest risks are left behind. Finance tends to flow to places where donors have a presence and to countries with strong institutional capacity to implement projects. Investors seek predictable environments to generate returns and are reluctant to invest in countries with poor institutional and market settings and records of corruption.

When vulnerable countries receive adaptation finance, it doesn’t always reach the communities most at risk. Adaptation funding, driven internationally and directed nationally, has little input from the local level, where expertise is often lacking and, in many cases, funds are lost to corruption before they reach their beneficiaries.

Despite these challenges, climate adaptation will hopefully progress. Nevertheless, Southern African countries need adaptation policies and projects across all sectors. The economic, social and environmental costs of not adapting are enormous