PROFILE • PROF. JOHN D. LIU

Hope in Landscape Restoration

Professor John Dennis Liu is a world-renowned environmentalist. He firmly believes in the restoration of ecosystems as a solution for the future of humanity and the preservation of the planet’s diversity. His active commitment to the cause bears witness to hope and is an inspiration for the global community

BY Marian Pallister | Chair of Pax Christi Scotland

THERE ARE many definitions of the term ecosystem, and few of them serve to make the meaning clear to those of us of a less-than-scientific mindset. Yet this is a word on which the future of our common home hangs. If we don’t have successful ecosystems, we don’t have food, we don’t have water, we don’t have life.

National Geographic’s library explains an ecosystem as ‘a geographic area where plants, animals, and other organisms, as well as weather and landscapes, work together to form a bubble of life’.

Rather more dramatically, John D. Liu says, “Ecosystem maintenance, or as we call it here ‘landscape restoration’, is key to addressing all of the problems that humanity is facing at this time.”

Commonland Foundation

‘Here’ in this case is the Commonland Foundation, a non-profit organisation with its headquarters in the Netherlands, which seeks to identify the viable solutions that our world needs. John D. Liu is its ambassador, and his words confirm what his work is all about—sharing the possible answers to the mess we have made of God’s gift to us; answers that will turn us into far better stewards of the earth than we have been in the last couple of centuries.

This requires teamwork: scientific institutes, business schools, farmers and experts all working together for global land restoration. The face of the Commonland Foundation (and indeed of landscape restoration) has become that of John D. Liu, a documentary cameraman in a battered hat who has brought into our homes the idea that it is possible to halt the damage of climate change and restore forests, agricultural land, and most importantly, sources of water where lands have been badly impaired.

Of course, this presupposes that the world’s leaders will take the actions needed to allow such restoration to continue to flourish: their pledges on renewable energy and carbon footprint reduction must be kept and improved upon.

If we want hope to take the place of the despair so many of us are feeling right now, then we need only look to the films produced by Liu which are shown around the world by major distributors. Today we can see some of his work on YouTube, just by searching for John D. Liu.

Liu has dedicated himself to the task of bringing hope to the public, and in 2013 he received the Communications Award from the Society for Ecological Restoration based in Washington, D.C, USA. A film about this eco-committed film-maker, called Green Gold, produced by VPRO, an independent Netherlands-based media organisation, won a Prix Italia award, and the aptly named Hope in a changing climate*, produced by Liu was named the best ecosystem film at the International Wildlife Film Festival in Missoula, Montana State, USA.

Who is this man behind the camera, this ambassador for land restoration, determined to show the world what can be done?

Early life itinerary

John Dennis Liu is a Chinese American, born in 1953 in Nashville, Tennessee. His father was Chinese, his mother American, and much of the first half of his life was spent in the United States. Looking at the pathway of his studies, it suggests a youngster not entirely sure where he was headed.

After Bloomington High School, he studied journalism at Indiana University in Bloomington, but he also studied music at the University of Vermont. Journalism won. In 1979 he went to China for the first time because of worries that his Chinese grandmother was growing old and had not met her American grandchild, now headed for the age of 30.

There were tensions between the United States and China at that time, but the situation eased and Liu not only studied the Chinese language at Beijing Language and Culture University but also set up the CBS News Bureau there in 1981.

Opening the eyes of the world

For a decade, he worked as a producer and cameraman, but then decided to leave day-to-day journalism behind and make films. Such was his talent that he was employed by many of the major European networks to produce nature documentaries, with the BBC, Italy’s RAI, the German ZDF and CBS, screening his ground-breaking work.

He wasn’t just pointing a camera—he knew his stuff, having followed yet another study path: ecology. There was a Studies Fellowship in Applied Sciences and the Built Environment in Bristol at the University of the West in England. He stayed on in the UK to study at Rothamsted Research, one of the oldest agricultural research institutions in the world, founded in 1843 by John Bennet Lawes. Here, Liu studied Function and Dysfunction in Terrestrial Ecosystems, and we see not just his interest but also his dedication.

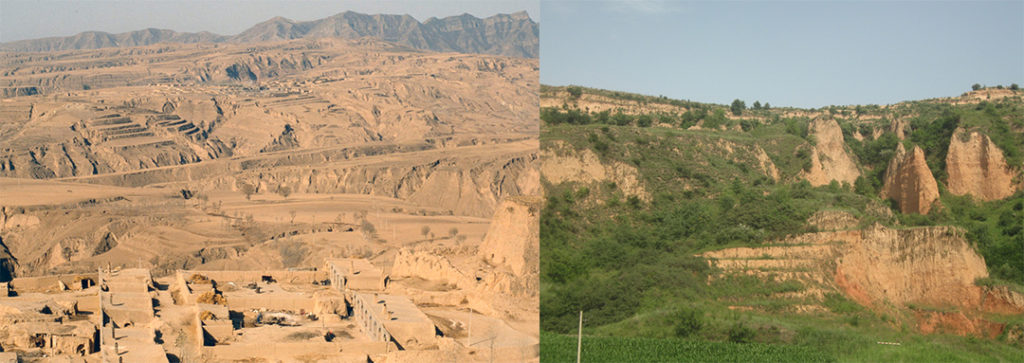

In 1995 Liu filmed a development on the Loess Plateau in China. The government there was funding a project to transform eroded land back into a green and productive area. It was further inspiration for Liu, and in 1997 he became director of the Environmental Education Media Project. We might say that this was when his real work began, showing the world that we can indeed restore the ecosystems we have so carelessly and wantonly destroyed. His TV documentaries have informed not just China but the world about ecology and sustainable development.

If we have realised in recent decades that since the industrial revolution, humankind has destroyed so much—in particular, biodiversity—then Liu may have been the man behind the documentary that switched on the lightbulb. He has educated us to understand that climate change’s higher temperatures are creating the desertification we see in vast areas of the African and Asian continents. But he has also taken us to Jordan, Ethiopia, and China to see where there has been re-greening of such areas—winning awards, yes, but that’s not what Liu is about. This is a man on a mission.

Landscape restoration

Liu became a visiting fellow with the Faculty of Natural Sciences and the Faculty of the Built Environment at the University of the West in England from 2003 to 2006, and in 2006 he was named the Rothamsted International Fellow for the Communication of Science. He was also an associate professor at George Mason University, Fairfax County, Virginia, USA, as a part of the Centre for Climate and Society, and a senior research fellow at the International Union for Conservation of Nature with headquarters in Gland, Switzerland.

In 2009, he began working with the Commonland Foundation, bringing together private investments to initiate large-scale land restoration around the world. Today as its Ecosystem Ambassador he is the front man who can convince governments, corporations, organisations—and us—that habitats aren’t lost, that we can continue to grow food enough for all, that clean water and sanitation, the UN’s sixth sustainable development goal, are achievable.

In 2016, Liu founded the Ecosystem Restoration Camps movement, now grown to more than 50 camps on six continents

In 2016, Liu founded the Ecosystem Restoration Camps movement, now grown to more than 50 camps on six continents. Campers work together with local communities putting restoration strategies into practice and learning, as they work, about restoration techniques that can be applied elsewhere. Liu visualises a global network of camps supporting what Commonland calls “the emergence of a fully functional, peaceful, abundant, biologically diverse earth, brought about through co-operative efforts for the ecological restoration of degraded lands”.

Of course, landscape regeneration doesn’t happen overnight. It can take a generation to restore struggling ecosystems. However, in the Baviaanskloof and Langkloof catchments in South Africa, working with the Commonland Foundation, progress has been seen in just a handful of years. New businesses have been created, agricultural and traditional goat farming practices have improved and become more sustainable, and degraded hillsides are being restored.

Initiatives in South Africa

The South African project is just one of many that Commonland has initiated around the world. Liu has helped inspire so many people to become involved in restoring lands, especially through these Restoration Camps.

Liu sees land restoration as a lifetime commitment—and knows his lifetime is not sufficient to make the restorations our common home requires.

He has written: “We are collectively facing on a planetary scale, climate change, biodiversity loss, floods, droughts, wildfires, pandemics, inequality, food insecurity, unemployment and the potential for economic collapse.“

As chair of a peace organisation, the inseparable links that he makes between the climate emergency and peace resonate strongly with me. He says,

“As we see fault lines emerging that endanger our peace, our health, our prosperity and ultimately human civilization, it is important to learn from past efforts that we have been grappling with these questions for years and decades. It is clear that the message of hope, renewal and regeneration of natural systems and human society achieved by working for the Common Good is urgently needed and greatly welcomed throughout the world.”

As Commonland Foundation’s ambassador, Liu believes the Foundation’s approach will ensure the ecological health of the Earth in ways that are fair and sustainable for people and all life.

Prof. Liu and Laudato Si’

In 2016 he said something that chimes with Pope Francis’s 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’. Liu explained, “We have to be very careful not to commoditise nature. We need to naturalise the economy. What this means to me is that natural ecological functions are more valuable than ‘stuff.’ When we understand that, then the economy is based on ecological function.”

He added: “That is exactly what we need in order to mitigate and adapt to climate change, to ensure food security, and to give every individual on the planet equal human rights. Suddenly we are in another paradigm. It’s similar to the shift from flat earth to round earth paradigm.”

Natural ecological functions are more valuable than ‘stuff.’ When we understand that, then the economy is based on ecological function

The man behind the camera shares much with Catholic Social Teaching and with Pope Francis when he urges us to stand in solidarity with our brothers and sisters.

The way Liu puts it is, “We need to realise that there is no ‘us and them.’ There is just us. There is one earth and one humanity. We have to act as a species on a planetary scale because we will all be affected by climate change. We have to come together to decide: What do we know? What do we understand? What do we believe as a species?”

Liu talks of ‘the economy of love’. It’s an economy that helps to bring the water of life to damaged communities. It’s a philosophy that politicians and captains of industry need to learn.

—

References:

Green Gold*

Hope in a changing climate**