REFLECTIONS • ANTHROPOCENE ERA

Our Human Condition and Water in an Era of Global Warming

Humanity has the capacity to destroy or preserve this planet. Global warming and urbanisation are currently straining world hydric resources. A global effort to preserve water can determine our future

BY ohann Tempelhoff | Water historian and extraordinary professor, Faculty of Humanities, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark Campus, South Africa.

IN 1957 the political philosopher, Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) published a book, The human condition, describing how major scientific breakthroughs since the 17th century, had changed our consciousness of the world. Her intellectual focus was on Sputnik—the first unmanned spacecraft to orbit Earth’s elliptical path in a mere 98 minutes. Arendt argued that people had started thinking differently in the 20th century. For her, it had everything to do with a consciousness of our collective human condition in a time of exponential intellectual growth.

Arendt contemplated the vitality of human activities and how they shaped societies’ collective mentality. By using science, technology and the arts, humans had produced motorised transport, Einstein’s Law of Relativity, and even nuclear bombs. Humans, she warned, had even become capable of the mass extermination of their own species.

Moreover, humans had started exploring the Universe—beyond Earth’s confines. Arendt juxtaposed her understanding of the human condition with the tipping point of individual and collective self-perceptions of eternity and immortality.

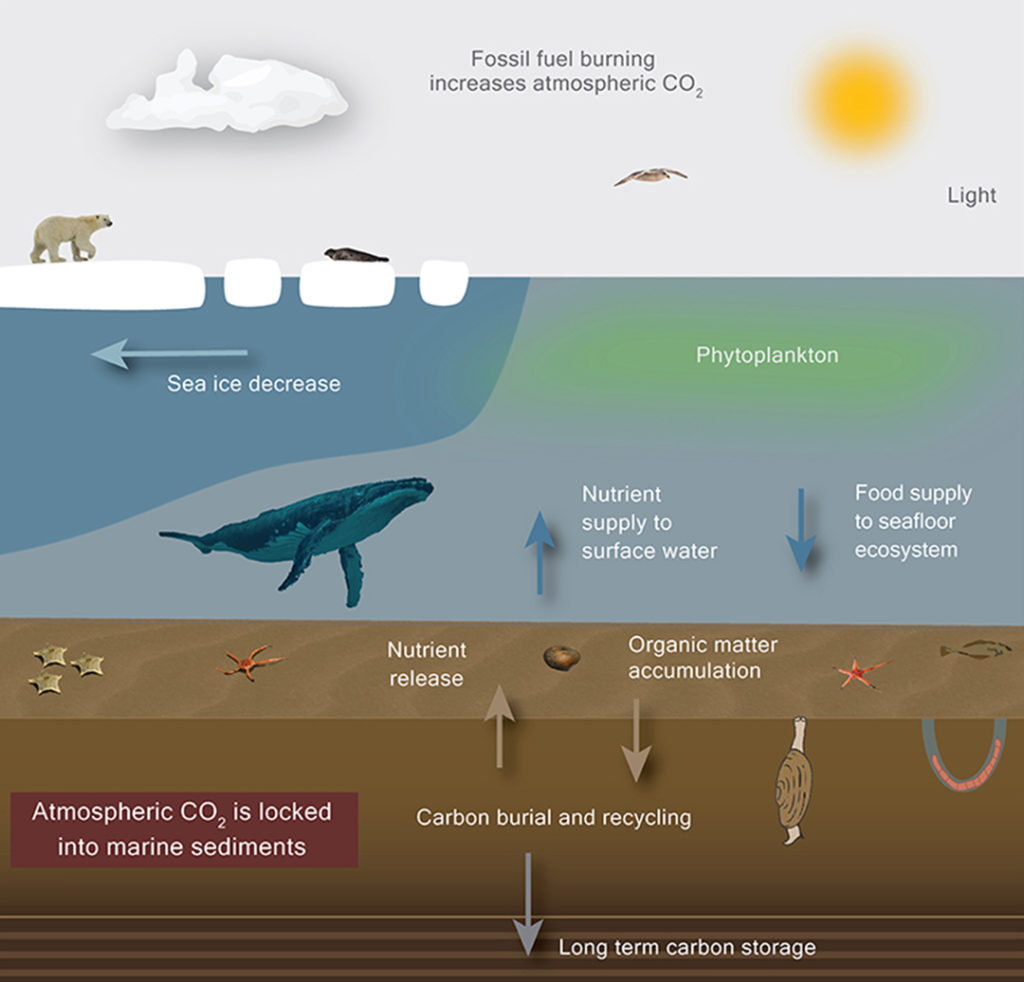

Science has progressed much since the 1950s. By the 1990s physicists, meteorologists and environmental scientists warned governments of the world about global warming. They confirmed that emissions of greenhouse gases (methane and carbon dioxide) and toxic chemical waste, had started warming up the planet. Earth has a long history of naturally warming and cooling over extended periods, but now we humans had started changing the very climate of our home planet.

The Anthropocene era and South Africa’s water challenges

As we drifted into a new millennium in 2000, the Nobel Laureate, Paul Crutzen, at a meeting of the Scientific Committee of the IGBP (International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme) in Cuernavaca, Mexico introduced the term, Anthropocene era, as a description of the time we are living in. Many scientists underscored Crutzen’s views. Humans (Anthropos) had indeed started changing the course of nature itself. The ‘new geological epoch’, Crutzen suggested, could well be named the Anthropocene era. Of all the animals on earth, we humans had scored a first—the capacity to change the planet’s climate. We may also be instrumental in its destruction.

Nowadays, environmental scientists use the Anthropocene era to describe the current dangerous trajectory of the human condition.

For one, climate change has a profound impact on South Africa’s water resources. We are one of the globe’s 40 most water-stressed countries. For many centuries we have thrived under extreme natural disaster conditions of drought and floods in what is today’s South Africa.

However, in the era of climate change, water-related floods and drought conditions have become anthropogenic disaster events. Now natural floods and droughts are compounded by how we humans have been abusing the environment. In April 2022, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and parts of the Eastern Cape suffered devastating floods. These floods turned into disaster events because we had anthropogenically changed natural environments to suit our own purposes. We had not planned ahead. Few precautions had been taken to safeguard human beings settled on what used to be natural shrublands, forests and even grasslands.

Since the 1970s the lack of rural and urban planning strategies, especially in South Africa’s informal settlements, claimed many lives. It wreaked havoc on human living conditions. Many urban residents had been left destitute under circumstances that had been shaped by a human condition, notable for its cunning ability to ignore the suffering of others. It was most evident in the lack of proper water and sanitation facilities in these settlements.

Unpredictable climate patterns

Between 2014 and 2020, South Africa experienced a countrywide drought. At the United Nations November 2021 Conference of Parties (COP) summit in Glasgow, South Africa’s climate change experts affirmed their consensus on future severe climate change. As members of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) they reported on a persistent climate change trend. Southern Africa is warming in the west. It will also become drier. Most rainfall will be unpredictable—mainly in the northern and south-eastern parts of the sub-continent.

Already we have some contemporary historical evidence. In 2016 the water resources of the Vaal Dam, a prime Gauteng water supply storage facility, started drying up. Thanks to erratic cyclonal events in 2017, the Mozambican channel weather turmoil was instrumental in flooding parts of Zimbabwe, Malawi, and the north-eastern part of South Africa.

Erratic cyclone conditions of this kind are destined to now determine our climate in southern Africa. The 2017 cyclone deposited much-needed stormwater in Mpumalanga Province that flowed into the catchment of the Vaal Dam. It saved the day for Gauteng Province—the country’s most populous region—thanks to a meteorological surveillance system of the country’s weather services.

In 2017 the City of Cape Town alerted its residents to prepare for a ‘Day Zero’. The city could soon be without water supplies. Western Cape’s customary winter rainfall had been erratic since 2015. In April 2018, within days of Cape Town running out of water, the first winter rainfall brought a respite to the city and its residents.

Urbanisation and connectivity

Sub-Saharan Africa is currently the region of the world with the highest urbanisation rate. In the mid-2000s, half of South Africa’s population was resident in urban areas. By September 2022 an estimated 66.7% of South Africa’s 60.9 million residents, lived in urban areas.

In urban areas, residents require copious water supplies, sanitation and proper stormwater infrastructure systems. Needless to say, there are frequent shortfalls in urban water resources and infrastructure systems in villages, informal settlements, towns, and the country’s cities. As more lands open up, plans are made to provide water and sanitation services. Often there are shortfalls in funding the infrastructure and ultimately even the water resources.

Our contemporary human condition is notable for its ability to be connected: mobile phones, computers, the internet and a vast array of social media platforms have connected us with countless numbers of people in many parts of the world. We are exposed to news, views, gossip and anger, but also humour. Experts now even speak of the ‘Multiverse’—a future human condition where our global intellectual feedlot is determined by algorithms and no longer our personal freedom to choose.

Water needs

How does the new Orwellian-type future impact our understanding of climate change and our access to water? Our body consists of more than 60% water. Females require on average 2.2 litres of water per day. Males need 3.2 litres.

Water is the prime natural renewable resource we engage with when we start every day. It helps take care of our hygiene, but also facilitates our food intake. We take water for granted.

Conserving water in the Anthropocene era of climate change should become part of our present human condition

Daily, hundreds of water sector workers in all parts of South Africa focus on water and related infrastructure services in the country’s urban areas. We seldom take note of the work they do—except when services collapse. Infrastructure systems in many parts of the country are overworked and under-maintained.

Estimates suggest that our daily per capita consumption of water in urban South Africa stands at 300 litres. In most urbanised countries of the world, per capita consumption stands at 175 litres per day. Our water sector experts suggest we should use about 200 litres per person per day. A major drawback is that as much as 60% of urban water supplies are lost, before they reach users, because of leaking pipelines.

Water preservation

We also unwittingly waste water. Think about daily brushing of teeth while the tap water runs. Why not shower instead of bathing? How regularly do we check up on potential domestic sewage wastewater leaks? What about re-using kitchen water for a backyard vegetable patch, or the flower garden?

The human condition in the realm of water appears to be focused on consuming, not conserving. We need to revise our understanding of the human condition in the Anthropocene era if we as humans aspire to live and thrive on planet Earth.

In the era of climate change, we are bound to face extreme conditions. Water may well become more scarce than ever before. Best present-day examples are 2022’s severe summer drought conditions, forest fires, floods and exhausted water resources in North America, Europe, north-eastern Africa, and Asia.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the recent destructive fires and floods in Australasia are stark reminders of what can happen in southern Africa. Conserving water in the Anthropocene era of climate change should become part of our present human condition.

—

References

Arendt, H. 1958. The human condition.

University of Chicago Press, USA.

—

Johann.tempelhoff@nwu.ac.za

Mobile: 02782 562 9510.