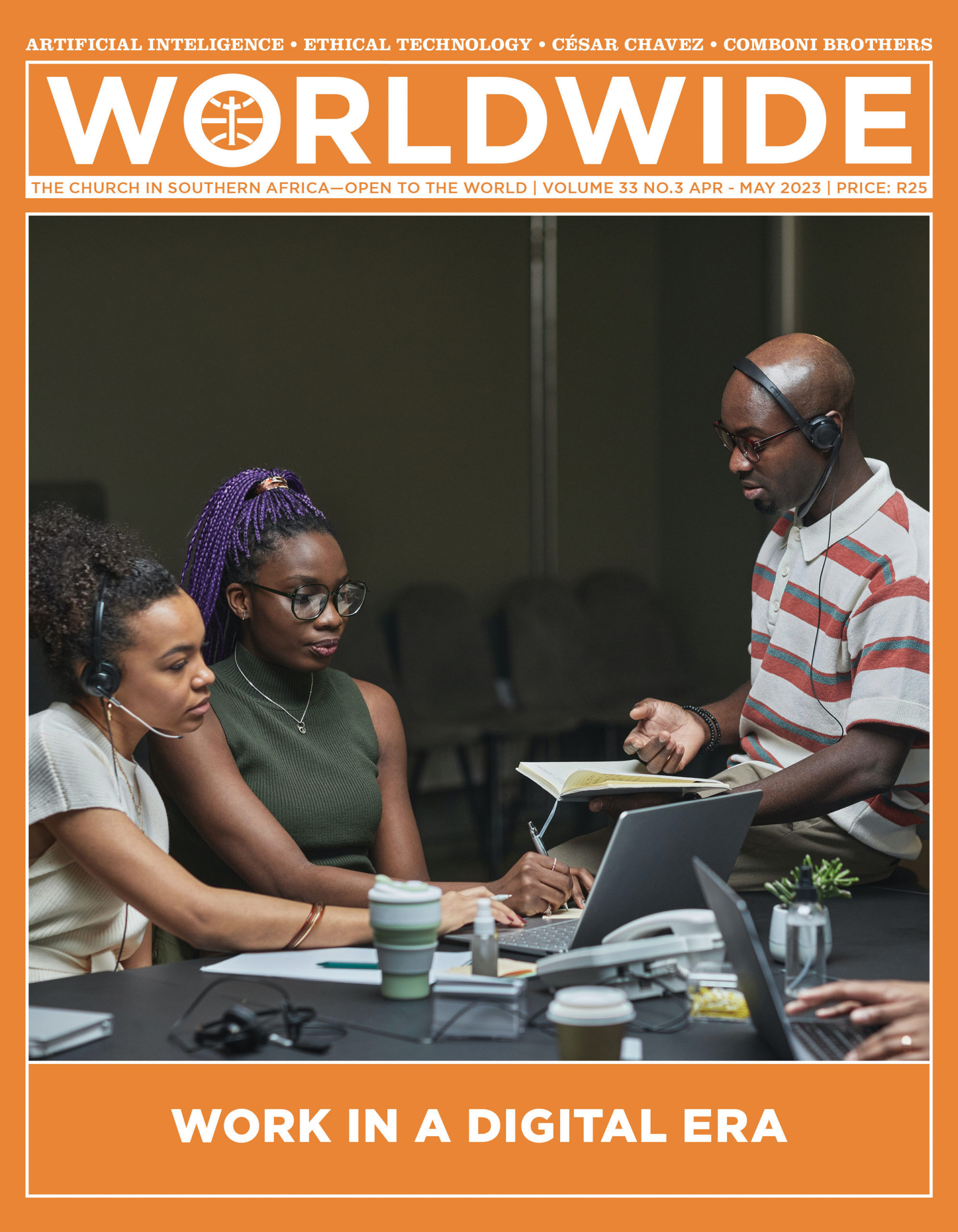

WORK IN A DIGITAL ERA

In the image we see a group of work colleagues discussing and planning their activities. They seem to have fun and an amicable relationship. The future of work passes through team work and co-operation in a spirit of mutual collaboration.

THE LAST WORD

ARE YOU ANGRY BECAUSE I AM GOOD? (MT 20: 1–16)

BY FR SILVANO FAUSTI SJ | BIBLIST AND WRITER

THE PARABLE of the Workers in the Vineyard contradicts, at its root, the logic of possession and claim; none can demand what is, instead, a pure gift of grace.

Those regarded as ‘first called’, both in Israel and in the Church, behave like Jonah: they are enraged to see that God is ‘merciful, forgiving, long-suffering, and of great love’ (Jonah 4: 2). They are attached to their spiritual goods, like the rich young man to his material ones. They are like the elder brother, who is angry to see that his father is good to his younger brother (Lk 15: 28). In this parable, those ‘first called’ even risk rejecting the Lord, because He is

magnanimous towards the last.

This parable is a gospel ‘in a nutshell’, similar to Lk 15: 1ff. It goes contrary to the ethics of capitalism, whether material or spiritual. It is not against the law or justice—the labourers of the first hour are given what is right—but it emphasises grace. God’s law and justice are that of love and liberality; His reward exceeds all merit: it is a reward, given out of mercy to all. For all, salvation is the free love of the Father. One cannot steal it by cunning or earn it by sweat: it is grace.

Eternal life, which the rich young man wants to have (Mt 19: 16), can be obtained not by doing something more, but by leaving everything. One must leave not only material goods but also spiritual ones. The Kingdom is of the poor in spirit (Mt 5: 3), of those who have become like children and accept it as a gift from the Father to His children in the Son. The privilege of the little ones and the least, is that, not deserving it, they understand that it is a gift. The others—the rich in spirit—will only accept it if, unlike the elder brother, they welcome the younger one; only if, unlike those who have worked since dawn in this parable, they are happy that their brothers of the last hour, have the same children’s salary as them.

This parable, along with that of the steward in Lk 16: 1ff, is even more irritating than Lk 15: 1ff because it uses economic language: it is a dig at our market-oriented way of conceiving love. The passage is divided into two parts: there are five different calls from sunrise until an hour before sunset (vv. 1–7): at sunset there is the moment of reward, starting with the last ones who receive the same retribution as the first ones, who, of course, complain (vv. 8–16). The focus is on the rebuke to one of the workers of the first hour, who does not accept that the Lord treats those of the last hour as He does. In this parable, Jesus brings back down to earth what was in the ‘beginning’: the way of the Father, who is benevolent to all His children, even to those who do not deserve it (cf. Mt 5: 45).

The Church, if it seeks salvation from her works, will no longer have anything to do with Christ: she will fall away from grace (Gal 5: 4). Christians, knowing that they have been saved by grace (cf. Eph 2: 5), putting aside bitterness, indignation, anger, clamour, slander, and all kinds of malice, are called to be kind to one another, to pardon as God has pardoned them in Christ (Eph 4: 31f).