WORK IN A DIGITAL ERA

In the image we see a group of work colleagues discussing and planning their activities. They seem to have fun and an amicable relationship. The future of work passes through team work and co-operation in a spirit of mutual collaboration.

PROFILE • WORK RIGHTS

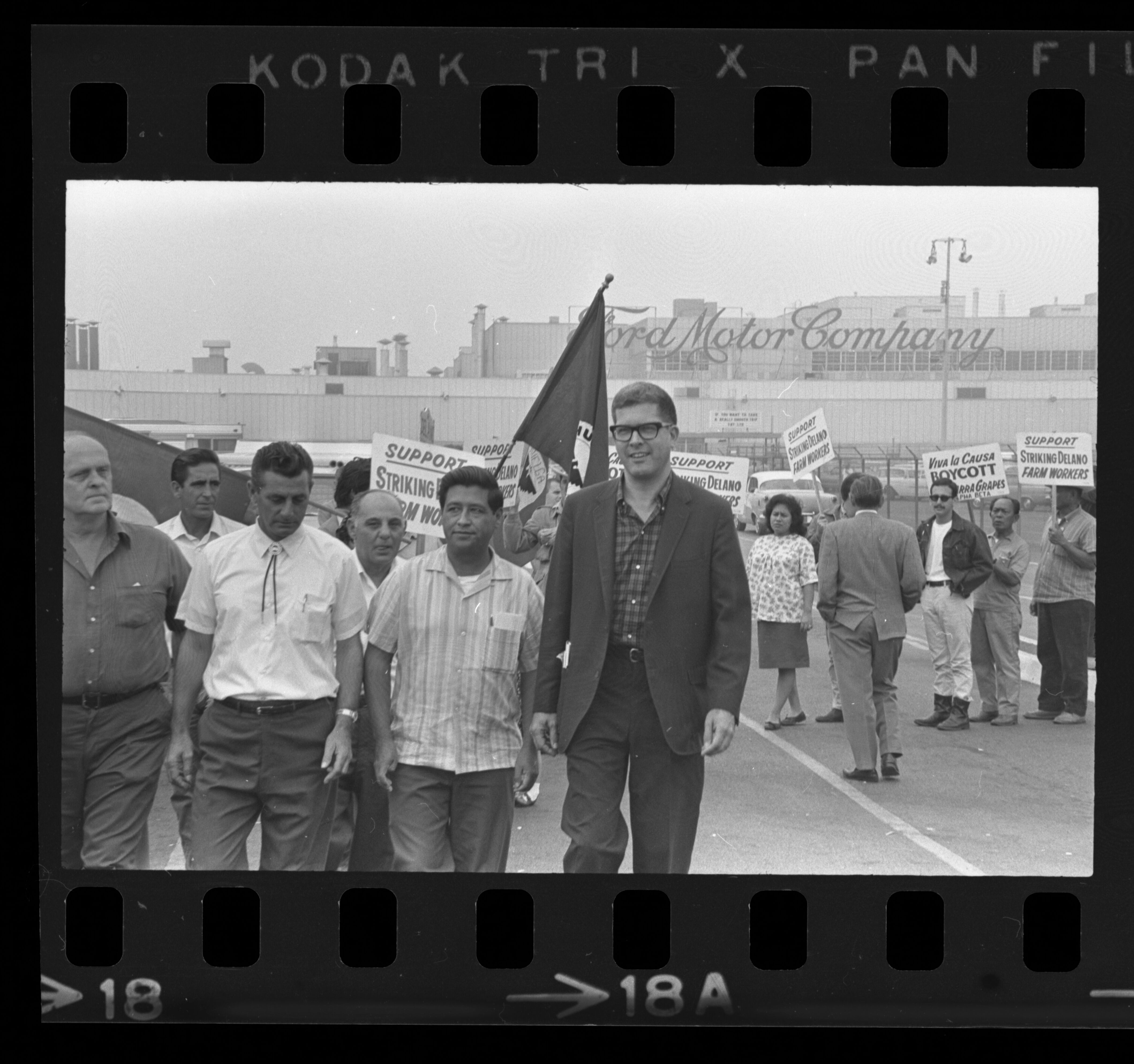

CÉSAR CHAVEZ, A LIFE DEDICATED TO SOCIAL JUSTICE FOR LATINOS

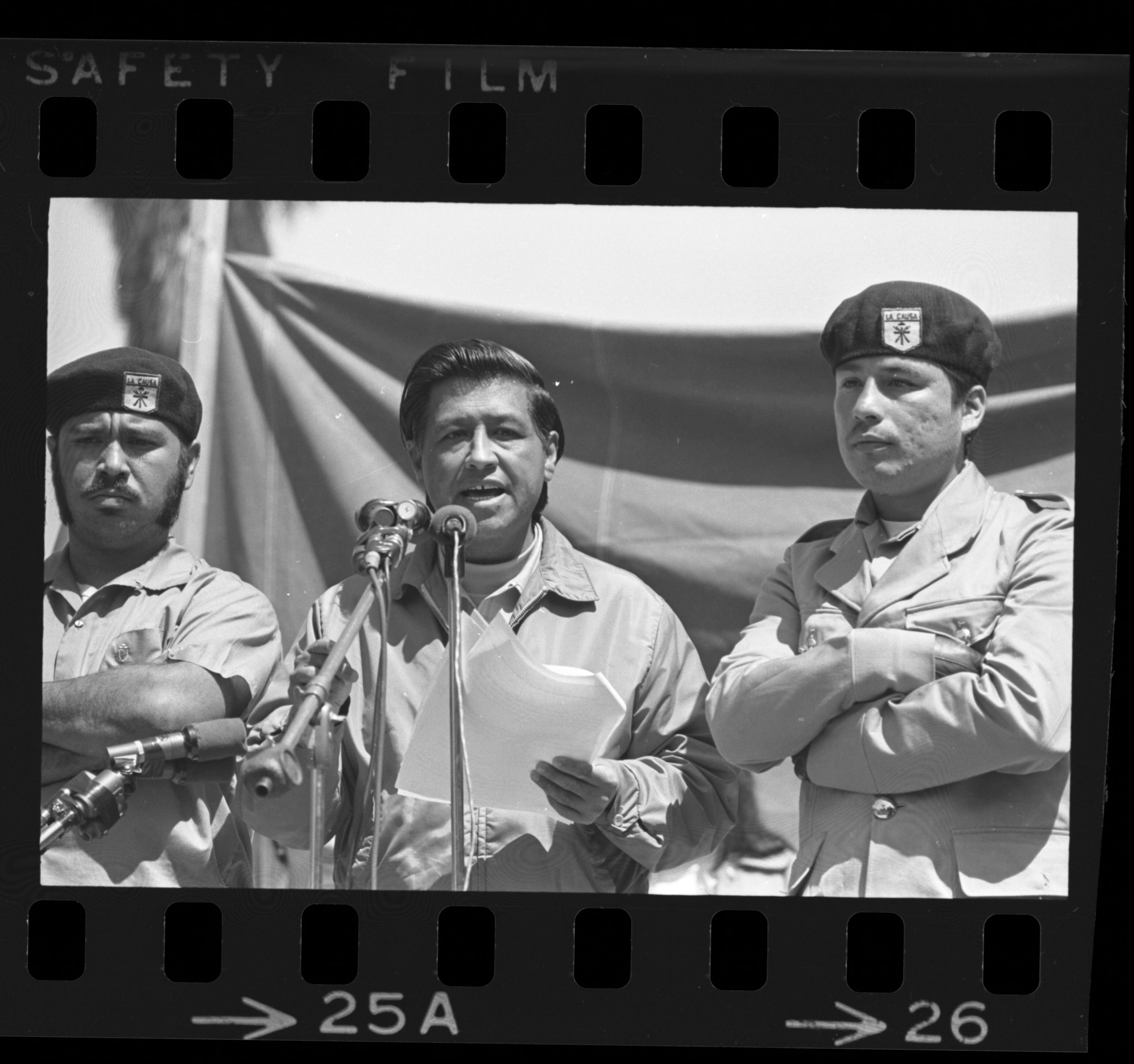

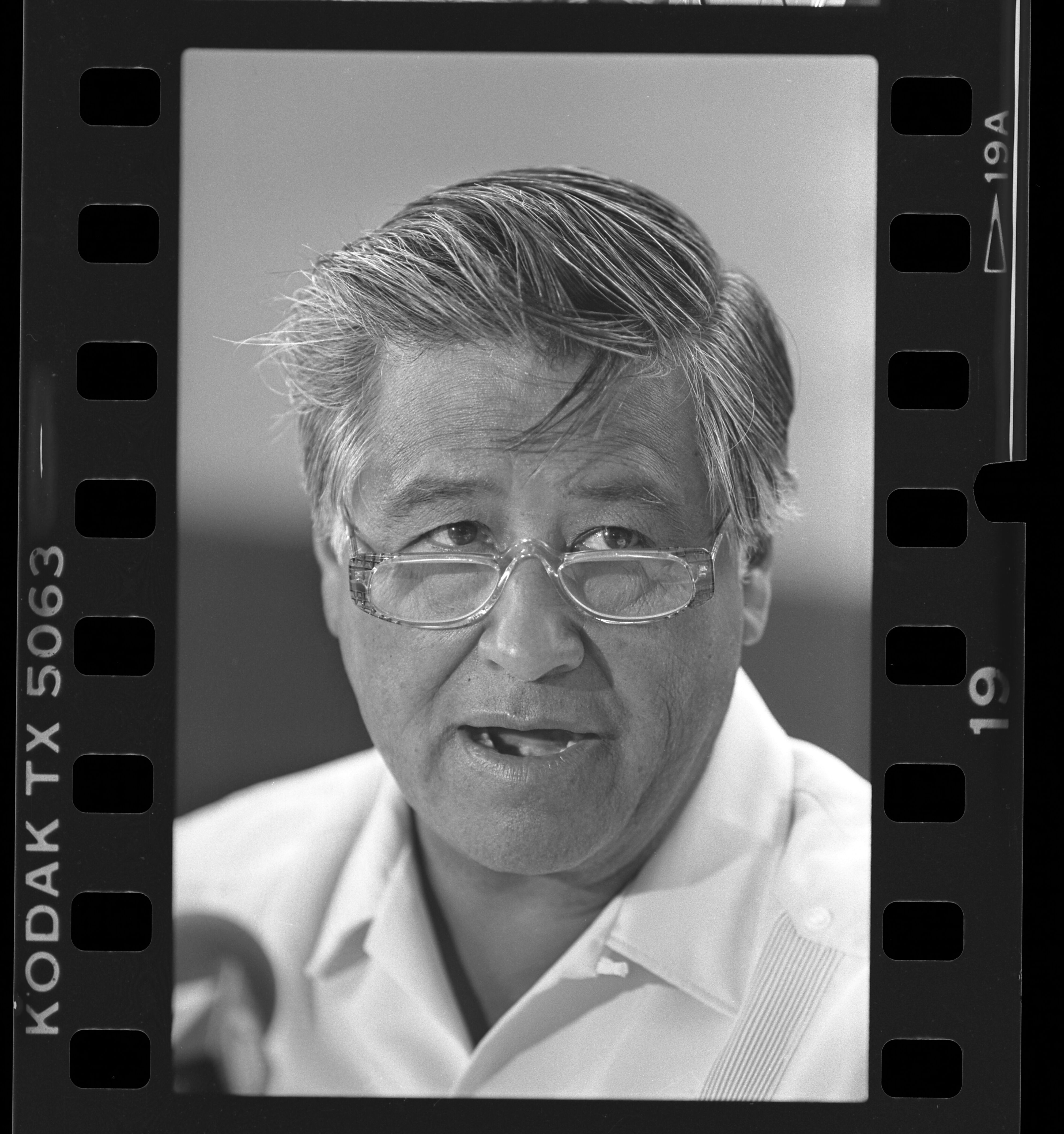

César Chavez is an inspiring Catholic activist, a prophetic voice in the defence of Latino migrant workers in the USA. He responded to the Social Doctrine of the Church with his life, to protect the common good and to restore the rights of the oppressed

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

YUMA, ARIZONA, bills itself as ‘The gateway to the South West’. It sits on the borders of California and the Mexican states of Sonora and Baja California, near the junction of the Colorado and Gila Rivers, surrounded by mountains and what the city’s publicity team terms as ‘lush agricultural fields’. The city was established there because it was the safest place to cross this coming together of two unruly rivers.

In the early 20th century, however, no tourists were appreciating the beauty of the area—just the miserable shacks of Latino farm workers whose conditions were deplorable. Many were descended from slaves, all were poor, and many went unpaid.

Family roots

César Chavez was born to Juana and Librado Chavez on 31 March 1927, and he was, by comparison, a lucky baby. The grandfather after whom he was named, had crossed from Mexico into Texas in 1898 with his wife Dorotea and eight children and had set up a wood haulage business near Yuma. César’s father was the youngest of those immigrant children, and he and Juana had ambitiously added to the family business a pool hall, a grocery store and a garage, but by the time little César was two years old, these ambitions had crumbled and Librado and Juana had to take the children back to their grandmother’s house to live. After all—who could afford to pay for a game of pool when labour was so badly paid? Who could shop in the grocery store when workers didn’t receive a wage for their work?

The Chavez family survived as it grew (César had two sisters and two brothers), but when the grandmother died in 1939 and her farm was sold by the local government to pay back taxes, young César saw this eviction from their home as yet another injustice suffered by Latino families. A small but significant example of the discrimination experienced by Latino’s was the fact that ‘César’ was not the boy’s baptismal name. He had been called Césario, but Spanish was a forbidden language outside the home and by the time he went to school, the name was shortened to fit the authorities’ regulations.

To hear the cry of the poor, to seek dignity for the marginalised was simply part of who he was

Theirs was a devout Catholic family, and César was growing up guided by Catholic Social Teaching. To hear the cry of the poor, to seek dignity for the marginalised was simply part of who he was. He and the family needed that faith as the Great Depression shaped the first dozen or so years of César’s life. The Depression was, of course, worldwide, and

in the United States, unemployment rose to 23 %, with trade falling by 50 %.

The family moved on, seeking work in California, picking avocados and peas, moving so regularly that the children’s education suffered badly. César was bullied at school for his poor appearance, and his low grades—although, despite it all, he remained good at mathematics. He left formal education at 15, after attending 36 different schools and became—yes, a peripatetic farm labourer.

Adulthood and social commitment

When the United States engaged in the Second World War, César joined the US Navy, returning to work on the land in A pivotal moment in his life came in 1947 when he joined the National Farm Labour Union (NFLU) and was involved in strike action, leading the picketing at cotton plantations.

There was a series of labouring jobs, and in 1948 he married Helen Fabela. As their family grew, this might have been a time when social justice took a back seat and César settled into looking after his own. However, his faith was a guiding element of his life, and meeting with

two European-American social activists whose concerns were for Mexican-Americans, gave him a wider vision of how to help the Latino community.

Fred Ross and Fr Donald McDonnell worked with César to set up community organisations, to encourage Latino’s to register to vote so that they would have a say in the running of the country, and he helped to build a church for the community—Our Lady of Guadalupe in Sal Si Puedes.

What did César get from this relationship with the two activists? Exposure to books that, not only helped his ability to read but also inspired him to take his activism to the highest heights. He was now aiming to follow in the footsteps of St Francis of Assisi, Mahatma Gandhi, and more immediately, the American labour organisers, John L. Lewis and Eugene V. Debs. Fred Ross and César grew the Community Service Organisation into a national organisation.

His family life suffered as he lived out a peripatetic campaigning existence, and there was growing opposition to what was seen as leftist activism. César not only rode the storm but also brought in the cavalry— the Catholic Church. Marco G. Prouty, in his book, César Chavez, the Catholic bishops, and the farmworkers’ struggle for social justice, explains that this struggle between Catholic workers and Catholic landowners split the community in California’s Central Valley during what was known as the Delano Grape Strike from 1965–1970. César went twice to the Catholic hierarchy for help and eventually in 1969, the bishops agreed to support the labourers and created the Ad Hoc Committee on Farm Labour.

That Committee sent five bishops and two priests to the strike scene and brought about a settlement after five years of conflict. The Church then openly supported César and the United Farmworkers Union in a battle over ill-paid lettuce production. César said the intervention was “the single most important thing that has helped us”. It was, of course, the bishops’ adherence to Catholic Social Teaching that swayed them into supporting César’s fight for farmworkers’ rights.

The farmworkers had suffered this exploitation for generations: the provision of shacks as a substitute for wages, no basic facilities, insurance, or medical provision. César’s organisation of this vast marginalised population into the National Farm Workers Association, which became the United Farm Workers, brought about a living wage and employment benefits through protest marches, strikes and boycotts and the support from the Catholic bishops. It was he who pushed forward the legislation for the first Bill of Rights for agricultural workers in the United States.

Non-violent prophetic voice

He said, “Like the other immigrant groups, the day will come when we win the economic and political rewards which are in keeping with our numbers in society. The day will come when the politicians will do the right thing for our people out of political necessity and not out of charity or idealism.”

He spent his life working to better the lives of the Latino immigrants

whose roots and faith he shared. It has been said that he is to the Latino community what Martin Luther King Jnr is to African-Americans. Perhaps the Presidential Medal of Freedom awarded after his death should have come sooner. A stamp in his honour is perhaps not sufficient recognition; perhaps the calls for his canonisation should be followed through.

This man died in 1993, having achieved so much

with the help of the Catholic Bishops

As a peace activist, for me, one of the most impressive aspects of César Chavez’ life and work is that he was totally committed to nonviolence. Those strikes and protests, those picket lines and hunger strikes were all carried out in the spirit of nonviolence and therefore all the more

impressive in that they were successful.

His people’s hardships had been his own. When the Chavez family moved to California, they had to leave their chickens, cows, horses and implements; the family treasures brought from Mexico by grannies and grandpas; from living on the family farm to living under a canvas, or Mum, Dad and five children sleeping in a car. It is unsurprising that his campaigns were for a minimum wage; unemployment insurance for farm workers; the farm workers’ right to collective bargaining; a life insurance

plan; and a credit union.

César said, “Once social change begins, it cannot be reversed. You cannot uneducate the person who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels pride. You cannot oppress the people who are not afraid anymore. We have seen the future, and the future is ours.”

What is tragic is that there has been a reversal. Only in 2023, new legislation is being considered in the US to protect Latino workers. Although more than 62 million Latinos now live and work in the United States, contributing $2.7 trillion to the economy, there is still marginalisation, discrimination, and the need to challenge the social, economic, and political barriers that affect them.

Exemplary life

César Chavez and the Union of Farm Workers were not only supported by American bishops and Pope Paul VI but by different faith traditions, and by politicians such as Senator Robert F. Kennedy, activists such as Dorothy Day and Martin Luther King Jr. César was praised as a man of integrity. As a devout Catholic, Chavez ended a 25-day hunger strike in 1968 by receiving the body of Christ, sitting next to Senator Kennedy.

In 1974, Pope Paul VI, the Pope who told us that if we wanted peace we

should work for justice, welcomed César Chavez to the Vatican as a “loyal son of the Catholic Church and as a distinguished leader and representative of the Mexican-American community in the United States.”

This man died in 1993, having achieved so much with the help of the Catholic Bishops. Of course, César Chavez had his faults and weaknesses. These are acknowledged in Miriam Pawel’s book, The

crusades of César Chavez—so the jury is out on whether this was a hero with feet of clay or a potential saint.

He is already regarded as the latter in Mexico and there is much still said in his favour: in 2019, a US university hosted an exhibition recalling his life and work entitled, History rediscovered: the Holy Alliance of the Catholic Church, Seton Hall University, and iconic labour rights activist, Cesar Chavez; there is a state landmark in his honour; and streets, schools and libraries are still being named for him in California. Barak Obama used César’s rallying cry of “Sí, se puede” (Yes, we can) in his presidential campaign to bring together the disempowered.

One of his sisters has said that the 2015 move to begin the process of declaring him officially a saint would have been dismissed by César as too grandiose. Perhaps César Chavez’ modesty should prevail.