WORK IN A DIGITAL ERA

In the image we see a group of work colleagues discussing and planning their activities. They seem to have fun and an amicable relationship. The future of work passes through team work and co-operation in a spirit of mutual collaboration.

SPECIAL REPORT • ON WORK

LABOURING FOR THE COMMON GOOD

The Church regards work as a means through which the person serves others, not simply as a means for the provision of material needs. She upholds the rights of workers and envisages that employer and employee can contribute to the good of all, especially to the marginalised in society

BY CALLUM DAVID SCOTT | PERMANENT DEACON, ARCHDIOCESE OF PRETORIA & PROFESSOR OF PHILOSOPHY, UNISA

Jesus, the worker

Before beginning His ministry, Jesus was known among those in Nazareth as a tradesman. In Greek, Jesus was a ‘τέκτων’ (Mk 6: 3), often translated as carpenter. However, this word means more than a carpenter, but rather a builder, who would have carpentry amid his skills (Campbell 2005; Keith 2014). Regardless of the precise work Jesus did, He understood the nature of His trade and of business and the salvific nature of work (Catechism of the Catholic Church 2000 §533). This is apparent in some parables found in the Gospels, wherein Jesus uses characters who are workers and employees, and of money and labour issues e.g. five parables (Mt 13: 1–23, 47–50; 18: 23–35; 20: 1–16; 24:45–51). Jesus was conscious of the treatment of workers: ‘the labourer deserves to be paid’ (Lk 10: 7). It follows that He realized the consequence for those who did not or could not labour: ‘you [will] always have the poor with you’ (Mt 26: 11). St Paul took this a little further: anyone who is unwilling to work should not eat (2 Thes 3: 10).

the ‘throw away’ culture. Old woman from a traditional society. Credit: pxfuel.com.

Church’s understanding of work

The Catechism (2000) holds the Church’s official teaching on work (§§2426–2436). Here, the Church explicates the purpose of the duty and the right of working for the sake of the human, which is not only for material provision. Work has deeper meanings: through it, the worker serves others because work involves difficulties and toil, it spiritually unites the worker with the suffering and crucifixion of Christ, and it enables the worker to fulfil their potential. Consequently, in working to provide, in maximizing talents, and in participating—in a small way—in the redemptive activity of Christ, the worker is dignified.

However, work is not to be romanticized, for the Church, inspired by Jesus (Lk 16: 20)—as a voice crying out for justice for the exploited working People of God— is aware of the tensions that arise due to

stakeholder interests in labour.

The preferential option for the poor

The post-Vatican II Church compels the People of God always towards making “the preferential option for the poor” (Fr Pedro Arrupe SJ in Hebbelthwaite 2007). The advancement of social justice is taken so seriously as to be codified into the Church’s juridical text, The Code of Canon Law (2013):

[The Christian faithful] are… obliged to promote social justice and… to assist the poor… (Can. 222 §2).

A litmus test for discerning present labour-related social justice issues is by determining the situation of people living in dire poverty by considering indices of statistics on employment rates. For our own country, South Africa, the International Labour Organization’s modelled estimate for 2022 indicates that 36% of all adults over the age of 25 are unemployed, with gender disparity increasing the figure to almost 40% for women.1

1 cf. https://www.ilo.org/shinyapps/bulkexplorer41/?lang=en&segment= indicator&id=UNE_2EAP_SEX_AGE_RT_A.

Across the globe, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic continues to be felt in countries’ workforces not having recovered to pre-pandemic levels due to national and international lockdowns which prevented the activity of work in many instances (International Labour Organization [ILO] 2022). According to the ILO, in 2020, five million workers worldwide joined the category of the working poor, merely because one has work—whether formal or informal—does not translate into a situation of being able to make ends meet, let alone to flourish.

A dynamic of care must enter all aspects of the

economic relationship, so that the business may

be humanly sustainable

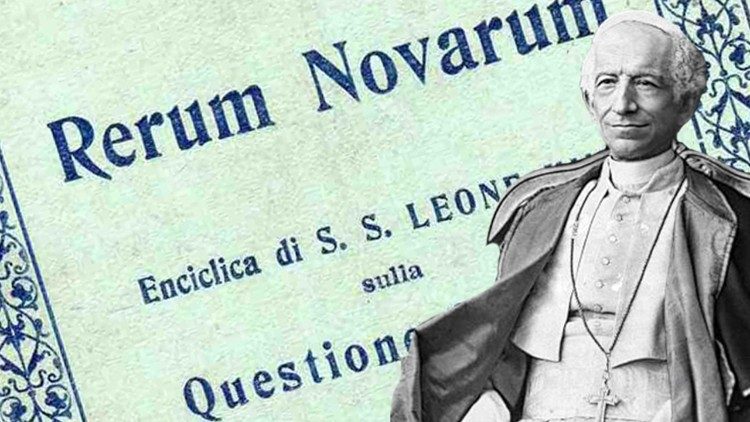

Apart from the Catechism’s reflections on work, the Second Vatican Council’s Gaudium et Spes (1965) and the encyclical letters which popes have written from the latter 19th century on work—among these, the first, Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum (1891), followed by Pope Pius XI’s Quarageismo Anno (1931), Pope St John Paul II’s Laborem Exercens (1981) and Centesimus Annus (1991), and Pope Benedict XVI’s Caritas in Veritate (2009)—there are other instances of support to labour movements given by different popes. During late Communist times in the 1970s in Poland, a groundswell of trade unionism began (Karabel 1992). On the 16th of October 1978, a Pole was elected pope, Karol Wojtyla (John Paul II), and by June 1979, he returned to Poland: a pope in a Soviet land! The impetus given by Pope John Paul II to the labour movement for change against the Soviet state cannot be underestimated (Weigel 2003). On Warsaw’s Victory Square, Pope John Paul (1979) praised the sweat of the Polish people’s labour “in the fields, the workshop, the mine, the foundries and the factories… creative work in the universities, the higher institutes, the libraries”. The history of Solidarność and the fall of Communism bears testimony to his just, motivating message to his subjugated people.

Wealth for the common good

Pope Francis (2021) gave a prophetic and challenging reflection on labour in his message to the 109th meeting of the ILO. He covered the critique that Catholic Social Teaching gives on labour in the contemporary world: by placing the human person—in her varied occupations, settings, and situations—at the heart of the Church’s considerations which are for the common good of all people, most especially of the vulnerable. through “…illness, age, disability, displacement, marginalization or dependency” (2021). To achieve this common good, Pope Francis invites all people involved in labour, whether factory owner or dustbin collector, to re-imagine work by moving beyond “the past fixations on profit, isolation and nationalism, blind consumerism and denial of the… discrimination against our ‘throwaway’ brothers and sisters in our society.” The Pope is not asking business not to make money, but to approach wealth generation differently, that is, in a way more sustainable and more equitable for the greatest number of people, as opposed to the capitalist limitless expansion of bank balances of the very rich. This, the Holy Father identifies as the vocation of business owners, for it is only through the utilisation of their skills, that wealth can be produced for the common good, such that the lives of all people can become more liveable and more bearable. Herein lies a subtle critique against blatant capitalism, for economic activity, in producing wealth should do so for “the development of others and to… [eliminate] poverty.”

To conceptualise human labour in this radical model, it is necessary to move away from comprehending work as a means to produce, instead considering it to be a relational activity through which the generation of wealth occurs. Work as a relationship lays the responsibility for its healthy continuance upon all parties involved, e.g. the business owner who has injected her capital into a company to open it, is as important as the person who cleans the premises of the business, for without the capital, the business would not be, but without the cleaner, the customer may be unlikely to return. A dynamic of care must enter all aspects of the economic relationship, so that the business may be humanly sustainable.

Migrants and informal economy

This dynamic leads to the consideration of the employment and abuse of those who are most vulnerable worldwide, namely, migrants and refugees. Within the South African context, the Immigration Act 13 of 2002 and its amendments of 2011 make it illegal for any foreign persons to be employed in this country and are not permitted to work according to their immigration status (§38.1)—but many people who fall into these categories are employed. Often these are the people who perform what Pope Francis (2021) calls “dangerous, dirty and degrading” work. Whilst the Church deems it a right for all workers to be guaranteed a just wage for work done, in the case of migrants and refugees, underpayment is common, and because they should not be working, they do not have any legal recourse. The relational dignity that should be accorded them is removed. Moreover, their ‘illegal’ status, sees to it that they are not included in those who receive benefits such as health care, and in some countries, they cannot access the public health care system either.

The Holy Father points out a similar crisis of care that also faces legal nationals in countries where there is a significant proportion of the population engaged in informal work. In the South African setting, the informal economy comprises almost 30% of the gross domestic product (GDP) (World Economics 2023), which logically includes a huge proportion of the population. These workers do not have ‘social protection’ in the form of medical and life insurance and daycare, and many informal workers are women, who are more vulnerable than their male counterparts (Pope Francis 2021). While some trade unions exist to provide a degree of protection to the informal sector, most often, unions serve those in formal employment, and thus, are only mandated to safeguard the interests of members of their unions.

Credit: Jim Padgett/ Sweet Publishing/freebibleimages.org.

Although the behaviour of unionists in South Africa may at times be controversial, the Pope—along with the Church’s preferential option for the poor—emphasises that “joining a union is a right”, for it is a means by which the basic rights of workers are promoted against the abuses that often are meted out by employers. While Pope Francis calls for increases in solidarity between workers, he also challenges trade unions to embrace their prophetic call to be collaborators with the People of God in the advancement of the rights of workers. In a meeting with the Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGIL), the Pope (2022) highlighted labour concerns he considered as worthy of union uptake: safety in the workplace and the exploitation of workers. Rightly, he also reminded the unions that their membership should not be taken for granted because they exist to work on behalf of workers: “[t]here is no trade union without workers, and there are no free workers without trade unions.”

Employer and employee must see to it that they

contribute to the good of all, most especially

to the most marginalised in society

The Church’s teachings on labour do not follow the socialist line of thinking, dividing the ownership and the activity of labour and consequently pitting the two against each other. Following her usual methodology, the Church follows the middle path, that is, the route between divergent positions. In considering labour, it is neither the employer nor the worker who is favoured. Both have their obligations and their rights. If both wish to conceive of work in the manner in which the Church does, both employer and employee must see to it that they contribute to the good of all, most especially to the most marginalised in society—the anawim (Lk 1: 46–55)—for whom God’s people must ever prefer to contribute.