SPECIAL REPORT • REFUGEES

Calling for a Christian response to the Reality of Migrants

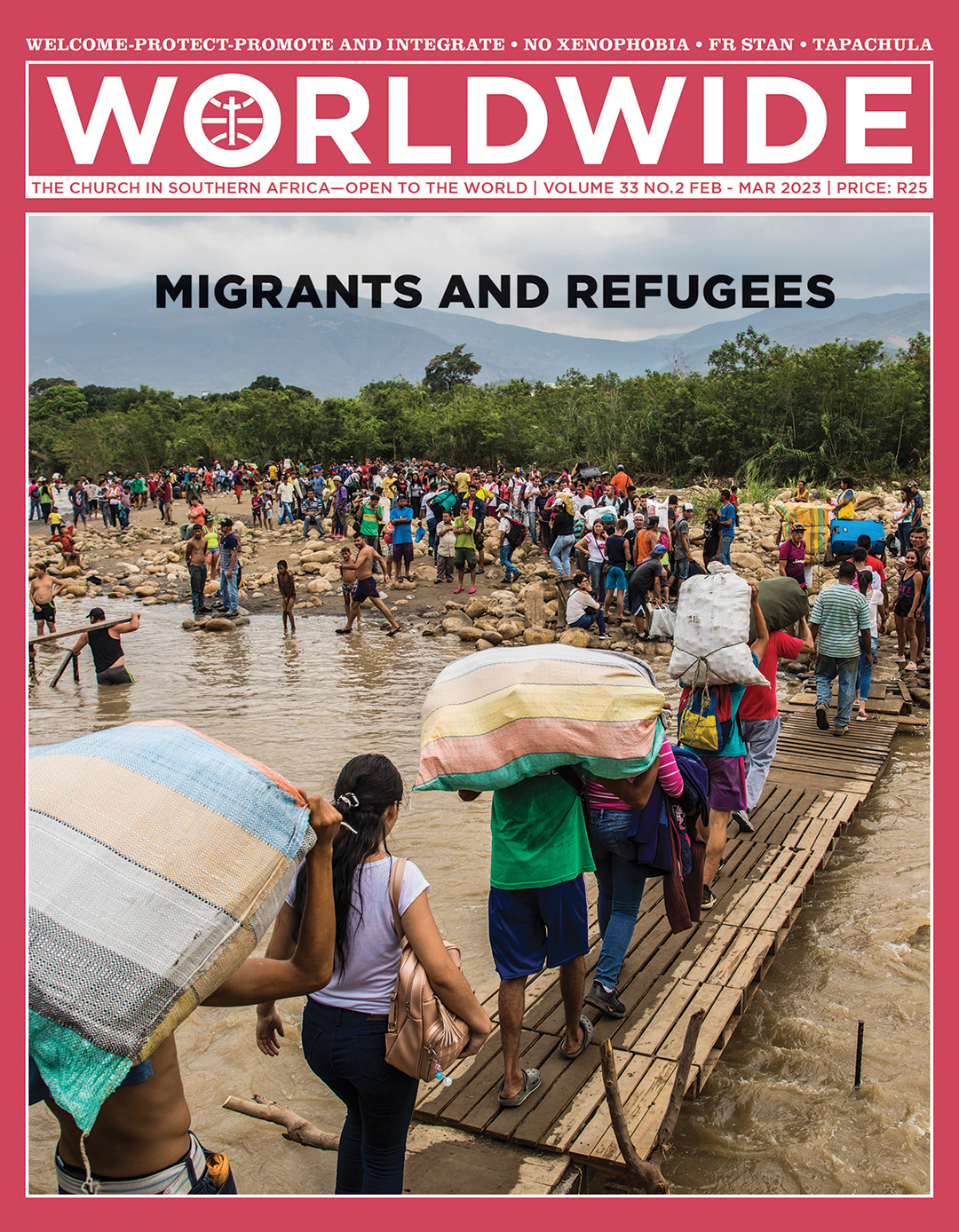

“Every minute 20 people in the world leave everything behind to escape war, persecution or terror” (United Nations, 20 June 2021).

BY Lance Thomas | Centre for Faith and Community, University of Pretoria

Christian communities and societies in general look at the global migration crisis. Faced with it, different attitudes become manifest

A global perspective

According to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), by the end of 2017, there were 25.4 million refugees across the world. By mid-2022, the figure had risen to 32.5 million. There are also 103 million displaced people worldwide. The 2022 report of the United Nations International Organisation on Migration (IOM) estimated that, in 2020, there were about 281 million international migrants—people living in a country other than their birth—meaning 3.6 % of the global population

In South Africa, the African Centre for Migration and Society at Wits University, states that “approximately 5.3% of people of working age were born outside the country”. In the United States, according to Erin Duffin (2022), “during 2022, 25 465 refugees were admitted into the country; a significant increase from 2021, when they were 11 411.”

P.W. Walsh (2022), at the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford also affirms that in 2019, “an estimated 388 000 foreign-born people living in the UK came originally to seek asylum; around 0.6% of UK’s total population of around 67 million.”

These numbers are surprisingly low and a far cry from the image of migrants streaming across our borders or millions of migrants ‘stealing our jobs’.

A need for reviewing procedures

In the context of the negative discourse on migration in the United States, a religious Sister, working at the border of the US, told me that migrants wait for months to get their documents in near-prison conditions, in overcrowded buildings. The Sister and her team were requested to make space for a plane load of war refugees fleeing from Ukraine who were given priority in their allocation and allowed to stay in single accommodation, pushing the rest of the migrants into even more overcrowding. The Ukrainian/Russian war has shifted the urgency with which the West perceives the global migration crisis, manifesting a double-standard approach.

From a South perspective, we have been calling for the update of refugee laws for years. The 1951 Convention with its 1967 Protocols is outdated, putting serious pressure on the migration system. UNHCR (1967) and the signatory countries have not managed to agree upon the necessary modifications and this has caused a serious backlog in the migration system. The obligation of non-refoulement—not sending someone back into a situation of possible persecution—is a great positive, but treating each person on a case-by-case basis has complicated the situation. Moreover, many local migration policies tend to become more restrictive on migrants’ rights, often pitting human rights against the national policy, making it more difficult for migrants to get refugee status.

A ‘Holy Family’ of refugees

The irony lies in a world hostile to migrants celebrating, as we recently did, a heavily pregnant Mary forced to leave her home to be counted in Bethlehem. After giving birth she, Joseph and Jesus had to “leave everything behind to escape persecution” and terror. Large tracts of conservative, mostly United States Christian groups, try to convince the world that Jesus was in fact not a refugee; their argument is rather simplistic saying that as Jesus moved within the territory of the Roman Empire, He never crossed a national border.

There are vast similarities between the rise of an exclusive, anti-immigrant and fundamentalist, in its religious approach, orthodoxy, to the rise of the German Evangelical movement under Adolf Hitler in the 1930s, which Karl Barth, the Swiss Calvinist theologian, so aggressively opposed (Dolamo 2020).

Pope Francis lamented in Fratelli Tutti that, “migrants are not seen as entitled like others to participate in the life of society, forgeting that they possess the same intrinsic dignity as any person. No one will ever openly deny that they are human beings, yet in practice, by our decisions and the way we treat them, we can show that we consider them less worthy, less important, less human.” [FT 39].

South African situation

In South Africa, several reception centres for migrants have been closed resulting in huge backlogs regarding the regularisation of documents. The policy uncertainty has left many migrants in limbo with some waiting since 1994, for a procedure which should take three months. The Congolese community, for example, needs to renew their documents every few months while others are renewed every two years. A short span of renewal coupled with more migrants entering the country, plus a scanty and poorly trained staff in the reception areas, compounds the problem. The special dispensation of Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa has also caused a humanitarian disaster. After 15 years of having a special visa, these rights have now been forfeited and migrants have to return home.

Since South Africa has a non-encampment policy, many migrants fend for themselves in the most precarious conditions, usually in townships, zones of gentrification around cities or in informal settlements close to places of work or business. South Africa finds itself in a financial decline due to years of mismanagement, theft from state coffers and poor infrastructure development. Recently it was revealed that in a hospital in Thembisa, a poor community, nearly a billion Rand was looted in graft. Within that context, a certain politician declared that “migrants are destroying our healthcare system”.

As the lives of people on the margins of society are becoming more precarious, compounded by the recent Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, many politicians and ordinary citizens use migrants as scapegoats for these larger social ills. New political parties and movements, such as Action SA (Youtube 2020), notorious for their xenophobic rhetoric, received considerable support in Gauteng’s last provincial elections. Their followers seem to be ordinary middle-class citizens around Soweto, Johannesburg and Pretoria, who see themselves as religious upholders of law and order. Others are well-educated people and even religious leaders with an anti-migrant discourse, who support them as custodians of Christian values.

Many local migration policies tend to become more restrictive on migrants’ rights, often pitting human rights against the national policy

Loren Landau (2022), Professor of migration and development at the University of Oxford, pointed out that scapegoating migrants is the narrative of a state that has nothing to offer to its citizens except hate and fear of the other, pitting the poor against the poor.

Since 2008, when South African society became synonymous with xenophobic violence, we have straddled the line between having one of the most progressive constitutions in the world; our inability to implement it; and a culture of care among our citizens protecting the rights of all. This fact leaves our society as a country ‘at war with itself’.

A Christian response

In Practical Theology, the term ‘responsible citizenship’ is currently used. In the context of African history of colonialism, with its missionary mandate of not getting involved in local politics, it could render church leaders ineffective in the protection of migrants. If the political narrative of using the term ‘illegal’ in regards to migrants continues, ordinary church members, under a supposed ‘responsible citizenship’, will shy away from dealing with the matter, following instead the directives of the state, and not reflecting on the harm imposed on the lives of vulnerable people.

Despite the many biblical texts clearly expressing that the justice of a society is reflected in the way it treats its “women, orphans and strangers” (albeit a little patriarchal) we still see our church mission limited to charity. In a city that faces poverty and inequality, land and housing injustice, urban exclusion, massive in-migration, contesting land aspirations, precarious housing, informality, and urban violence, the sum total of church effort cannot be limited to offering food.

At our Centre for Faith and Community at the University of Pretoria, we have sought to partner with Caritas to count the migrants in South Africa and with Kerk in Actie a Dutch Agency to develop groups of ‘church champions,’ people of goodwill who strive beyond establishing soup kitchens which often exonerate bad government policy. We want to train church members to take up social justice issues while still providing the food people so desperately need. As Helder Camara said, “when I give food to the poor they call me a saint, when I ask why they are poor they call me a communist” (Wagg 2014). For true Christians, keepers of their brothers and sisters, no matter where they come from, the Kingdom becomes their priority over building an exclusive Nation.