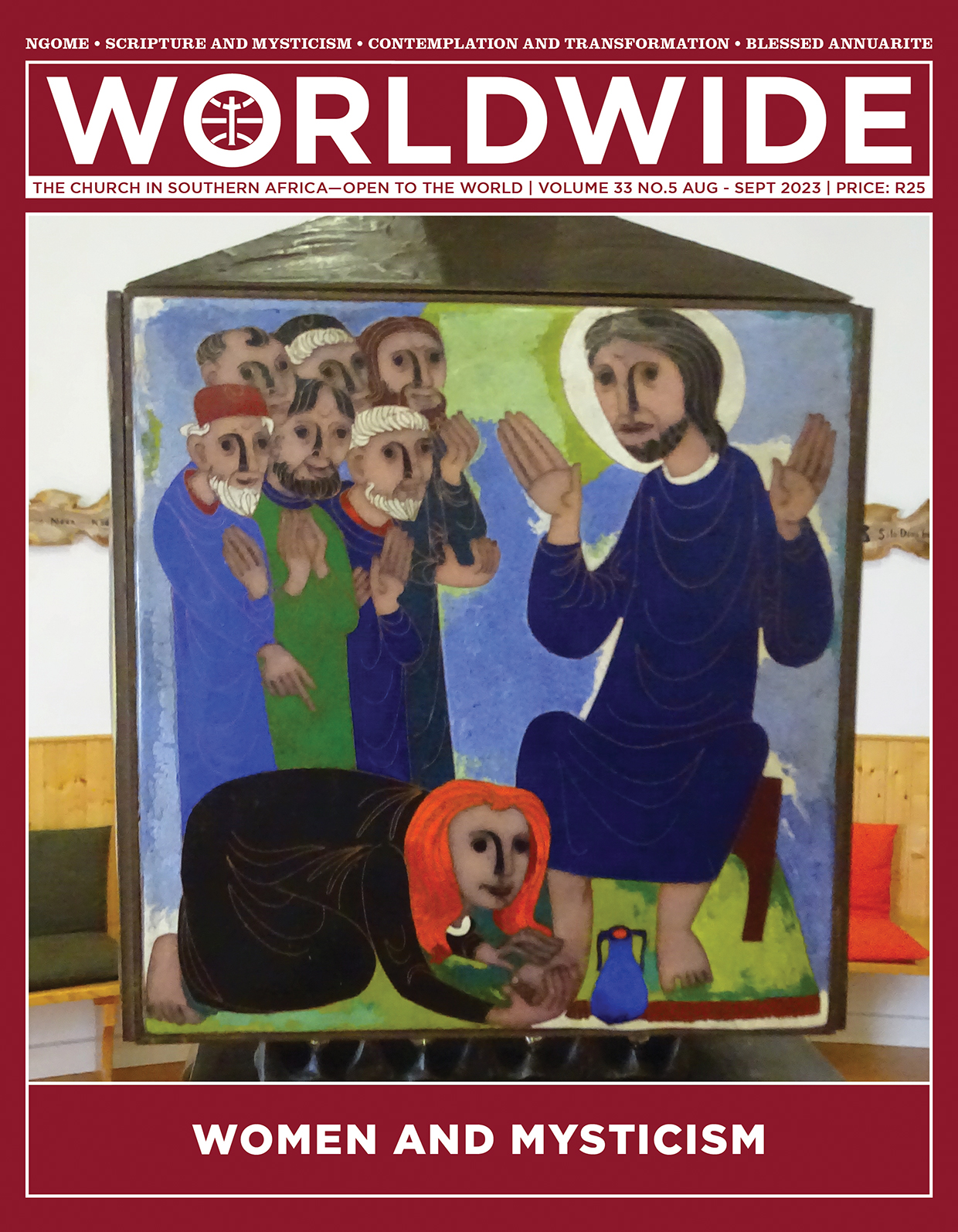

WOMEN AND MYSTICISM

Mary anoints Jesus’ feet at Bethany (John 12:1–8). The scene is part of a series which represents passages of women with a prominent role in the Scripture. The decorations are placed around the sides of the Tabernacle in the Chapel of Meditation at the University of Mystics in Avila, Spain.

Mary listens to and manifests her love for Jesus. Contemplation becomes the mesh in which her Spirit-led actions find their meaning and support.

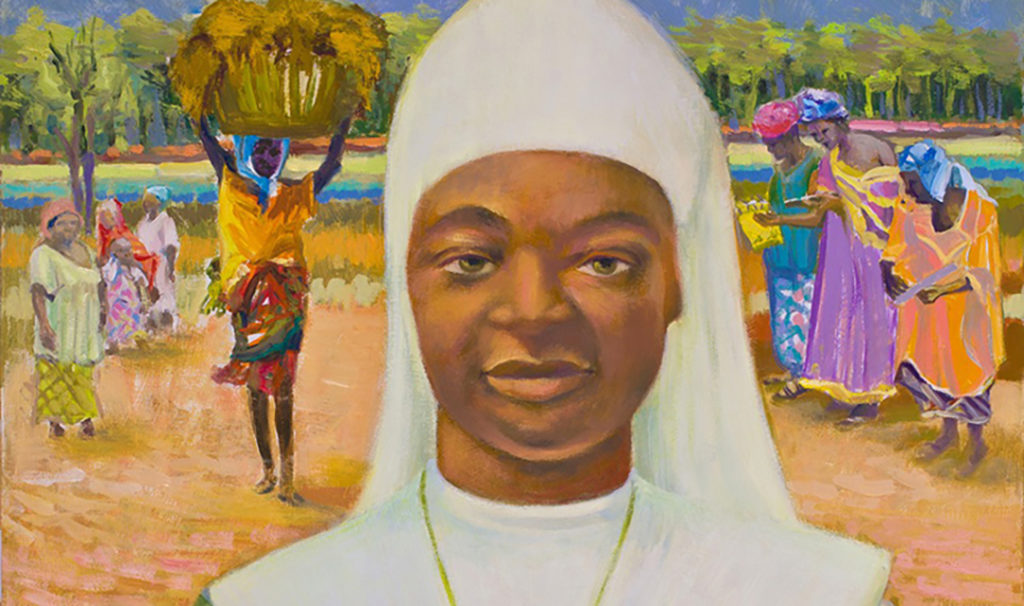

PROFILE • BLESSED MARIE-CLÉMENTINE ANUARITE

Defying Violence Against Women

During the Simba revolution, which took place after the oppressive Belgian colonization in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a young religious sister, Marie-Clémentine Anuarite, gave up her life as witness to religious consecration and commitment to forgiveness

BY Y MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

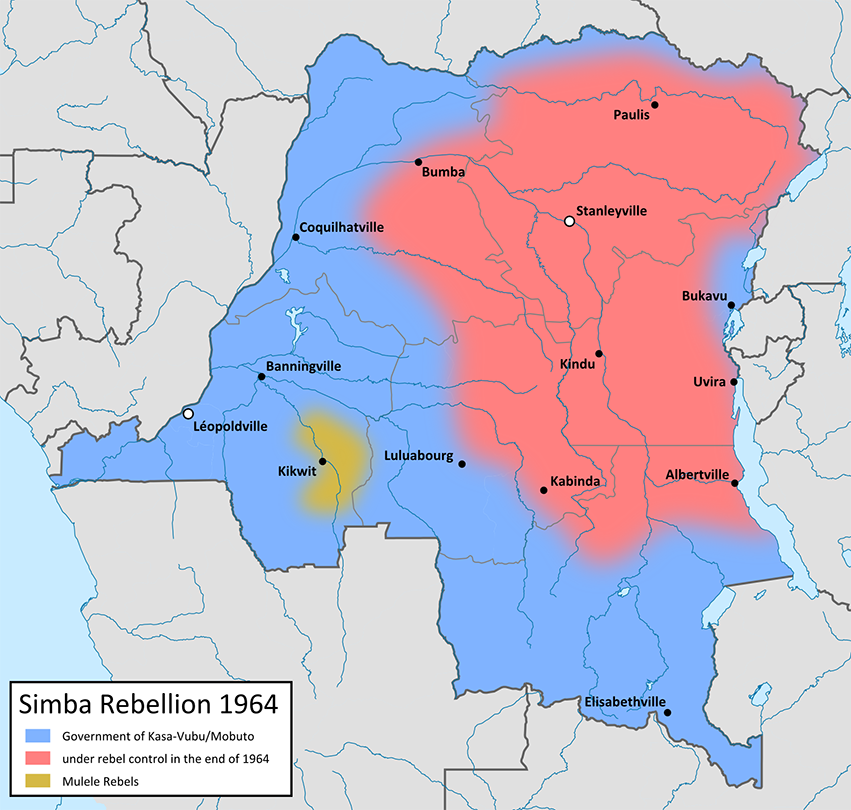

Colonialism’s history is never pretty, and that of the Belgian Congo or ‘Congo Free State’ (today’s Democratic Republic of Congo) is particularly ugly and cruel. It is little wonder that the atrocities that were commonplace during the reign of King Leopold II from 1885 to 1960 continued when the country became independent because the pitch for violence had been set and the inherited political insecurities could not possibly lead to a peaceful transition.

Gruesome atrocities

During Leopold’s rule, the 100 km2 of Central African rainforest that he claimed as his own personal property became little more than a labour camp producing rubber, making the king a fortune, and turning his tiny European country into a rising economic world player.

Those benefitting from that rise in the economic success of Belgium were no doubt unaware of the cruelty and depravation that fuelled their newly comfortable lifestyles, despite a brave journalist called Edmund Dene Morel trying hard to publicise the realities of life in the Congo.

During that era of colonialism, killings, famine and disease were responsible for as many as 10 million Congolese losing their lives

Leopold sanctioned amputation as a punishment for workers who did not achieve their quota. Rape and torture were used as punishments. Children were forced to become soldiers. The regime was, in effect, responsible for genocide. It has been estimated that during that era of colonialism, killings, famine and disease were responsible for as many as 10 million Congolese losing their lives.

Insufficient apology

In 2022, the current Belgian king conveyed his “deepest regrets” for the colonial humiliation and punishment suffered by the Congolese people. King Philippe addressed a joint session of parliament in the DRC capital Kinshasa, saying, “This regime was one of unequal relations, unjustifiable in itself, marked by paternalism, discrimination and racism.

The Congolese are justifiably less than grateful for the “deepest regrets” phrase, rather than a fulsome apology. Their country was left in chaos when independence was granted on June 30, 1960, and it is perhaps unsurprising that the violence meted out by rebels, government officials and military personnel throughout the 1960s mimicked that experienced during colonial times.

There were many innocent victims of that post-colonial violence, including priests and religious who were seen by some as agents of the West.

So many Sisters showed incredible bravery as they were subjected to obscene attacks. One was beatified as a result of her bravery and her willingness in her final moments to forgive her murderer.

Sisters´ ordeal

Blessed Marie-Clémentine Anuarite Nengapeta died on December 1, 1964, at the age of just 24 in Isiro, Haut-Uele, Orientale. This was during the Simba rebellion when her convent was invaded by rebel troops. The 46 Sisters of the Congregation of the Holy Family living in the convent were put onto a truck and told they were to be driven to Wamba for “security reasons”. Instead, they found themselves in Isiro, where they were taken to Colonel Yuma Deo’s house.

And there the nightmare began.

The other Sisters were sent to another house, while Anuarite was cajoled by one of the Simba leaders, Colonel Ngalo, to become his wife—we can take this to mean that he demanded sexual favours from her. Of course, she was terrified, but she was also determined not to give in. Soldiers were ordered to isolate and threaten her with death. She continued to refuse. Her Mother Superior came to defend her and was cruelly ignored.

The Sisters being held in the nearby house refused to eat. Two of them were taken to where the Mother Superior and Anuarite were being held. Given a supper of sardines and rice (which unsurprisingly, Anuarite was unable to eat), the Sisters were sent to bed in a room together but Anuarite was detained in Colonel Ngaio’s presence along with another senior soldier, Colonel Pierre Olombe, who had been brought in to assist with the “seduction”. In 2023, we can only call this attempted rape.

Martyrdom

Anuarite had told her Mother Superior that she was ready to die defending her virginity. The two colonels fell to arguing over their “prize”, Olombe deciding that rather than assist his colleague in raping the young woman he wanted her for himself. Her refusal led to vocal and then physical abuse, with Anuarite and one of the other Sisters, Jean Baptiste, being bundled into a car. When Colonel Olombe went to get the keys to the car, the nuns attempted to escape, infuriating their captors still further. Olombe caught the fugitives and sickening violence, witnessed by senior nuns, led to Sr Jean Baptiste collapsing with her right arm broken in three places.

Anuarite fought on, saying she would rather die than commit the sin these men wished on her.

Olombe was further infuriated and continued to beat her mercilessly. When he heard her say Christ’s words from the Cross, “I forgive you for you know not what you are doing”, he ordered his men to stab her with their bayonets. He ended this torture by firing his revolver at her chest, demanding that the rest of the nuns remove Anuarite’s body. She had not taken her last breath, which came around one o’clock in the morning on December 1.

Anuarite´s short life

Marie-Clémentine Anuarite Nengapeta’s life had been so very short. Had she lived to her birthday on December 29 that year, she would have just reached her first quarter of a century. Her mother, Isude Julienne, had disapproved when Anuarite left home to join the convent. She could little have thought that it would end in her daughter’s violent death.

But then, in peace times, however difficult they may be (and life in Belgian Congo was never easy), the words “rape”, “torture” and “looting” were situations of nightmares, not reality. Yet in the Far East, in Eastern Europe, Latin America and innumerable African states, countless women have experienced Anuarite’s reality since World War II alone.

Anuarite was born in Wamba. She thought she was going back there “for security reasons” as she set out on her last journey. Perhaps she thought of her early family life in Wamba as the vehicle veered off to Isiro. She had been the fourth of six daughters born to Amisi Batsuru Batobobo and Isude Julienne. Her father was not happy with six female children and evicted his wife in order to replace her with one who could give him a son. Such sexism was not rewarded: the second wife was sterile.

Blessed Marie-Clémentine Anuarite Nengapeta died on December 1, 1964, at the age of just 24 in Isiro

It possibly did not please him when as a child Anuarite vocally forgave her father for abandoning her mother. But then, this was a child with a growing faith and concept of right and wrong, good and evil.

Call to religious life

She attended a convent school and she particularly admired Sr Ndakala Marie-Anne. This led to her determination to follow a religious life. Because of her mother’s objection, she didn’t tell her about a truck that came to the local mission to take postulants to a convent. Instead, she simply boarded the truck. Her mother was, of course, frantic with worry and only found out the truth of her daughter’s disappearance when a village child who had seen Anuarite board the vehicle told her what had happened.

She could have gone to the convent and demanded to see her daughter, to have her returned home. Instead, Anuarite’s mother accepted that God’s will would be done. She had, after all, been baptised together with her daughter in 1945. Indeed, both mother and father attended Anuarite’s profession in 1959 when she took the name of Marie-Clémentine, offering two goats to the convent.

Yes, there was a time when her mother asked her to return home as things became financially tougher, but there was no real expectation that this nun in the family would ever be anything but that. Perhaps the persuasion would have been more persistent had her mother been able to see into the dark abyss that lurked ahead of her daughter as she journeyed through life; if she had known that she would face such abuse; if she had foreseen that her daughter’s body would lie for eight months in a common grave.

First Blessed Bantu woman

Had she persuaded Anuarite, the subsequent story would have been very different. That common grave was not her permanent resting place. Her body was reburied on holy ground eight months after that terrible night. And again, exhumed in December 1978 when it was found she had an image of the Blessed Mary in her right hand. Her remains were then moved to the cathedral in Isiro. On April 14 1977, the beatification cause began. The following year a cognitional process opened in the diocese of Isiro-Niangara and in 1980, Anuarite’s writings received theological approval. The due processes were followed, and on June 9 1984, Pope John Paul II beatified Anuarite during his visit to what was then Zaire, today’s Democratic Republic of Congo. She would be the first Bantu woman to be elevated in this way by the Catholic Church and her parents, who were present in the cathedral, must have felt very mixed emotions.

Blessed Marie-Clémentine Anuarite’s violent death strengthens those who today say “No” to gender-based violence

What in the meantime had happened to her killer? Olombe had been sentenced to death in 1965 but escaped from prison. When he was captured and returned there in 1966, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and he received a pardon in 1971. We may imagine that the sentence and the pardon were more to do with politics that with the death of a young nun.

Pope John Paul II forgave Anuarite’s killer at the beatification, which was attended by some 60,000 people—one of whom was said to be Olombe. Later, Olombe was said to have requested a meeting with the Pope so that he could express his remorse, but on the grounds that the man was unstable, the request was not granted.

Symbol against gender violence

Today, almost 40 years after Anuarite became Blessed Marie-Clémentine Anuarite Nengapeta, that young woman who steadfastly refused to give in to gender-based violence is being seen as someone who can change not only traditional attitudes of acceptance of violence against women but even the endless cycles of violence in society in general in the DRC.

In that, still often troubled country, the 16 days of activism against gender-based violence, which begin with the UN International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women on November 25, are seen by many women as days dedicated to Blessed Marie-Clémentine Anuarite Nengapeta’s memory. Her violent death strengthens those who today say “No” to gender-based violence.