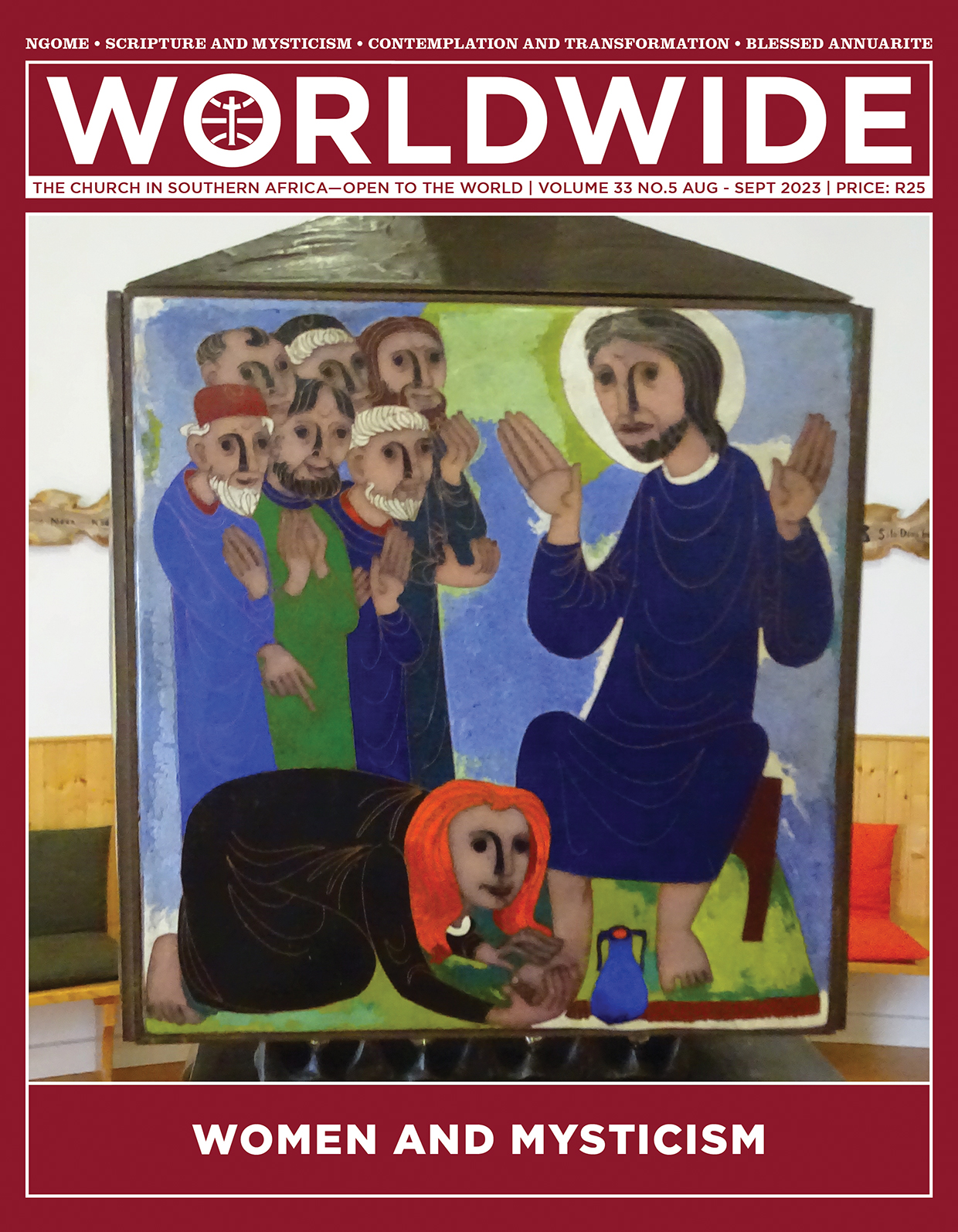

WOMEN AND MYSTICISM

Mary anoints Jesus’ feet at Bethany (John 12:1–8). The scene is part of a series which represents passages of women with a prominent role in the Scripture. The decorations are placed around the sides of the Tabernacle in the Chapel of Meditation at the University of Mystics in Avila, Spain.

Mary listens to and manifests her love for Jesus. Contemplation becomes the mesh in which her Spirit-led actions find their meaning and support.

INSIGHTS • WOMEN IN POLITICS

Credit: Embassy of the United States, Dar es Salaam/commons.wikimedia.

Transcending Gender in Politics

BY Mike Pothier | Programme Manager, SACBC Parliamentary LIAISON OFFICE, CAPE TOWN

A FEW years ago, I wrote a column in Worldwide about women in politics in South Africa. I wondered whether it was the case that women bring something different or ‘special’ to politics:

One sometimes hears it said that having more women in politics would increase the chances of consensus and agreement; they would be less belligerent and egotistic, more willing to see other points of view, and more likely than their male counterparts to put aside personal ambition in favour of serving the nation. Certainly, one can think of quite a number of women in our political life of whom that is true, but there are probably just as many of whom it is not. In any event, we should be careful of applying stereotypes, or of thinking that there is some kind of ‘female ideal’ that we should be trying to foster in political life.

Since then, we have seen many women achieving the highest office in various countries. Theresa May and Liz Truss became prime ministers of the United Kingdom. Nicola Sturgeon was first minister of Scotland for some years. Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand, Sanna Marin in Finland, Samia Suluhu Hassan in Tanzania, and Magdalena Andersson in Sweden all became their countries’ first heads of government. The United States also chose its first female vice president, Kamala Harris, in 2020.

So there does seem to be something of a trend—I have certainly missed out a few in the list above —but it is still not clear that the increasing presence of women at the pinnacle of their political systems has brought any noticeable change. Some of those I’ve mentioned certainly made a major impact on their countries, Ms Ardern perhaps most notably. The two Nordic women left less of a legacy, but at least they pioneered the possibility of female national leadership. Ms Sturgeon led Scotland with great firmness and determination, but shortly after stepping down, she was arrested following allegations of irregularities in her party’s finances—an outcome we tend to associate more with male politicians.

Liz Truss had an ignominiously short tenure of only 50 days, making her the shortest-serving prime minister in the long history of that office in the UK. During that time, she pursued economic and fiscal policies as egotistically as any male politician might have done.

Maybe the whole idea of the empathetic, unifying, self-giving female politician is nothing more than a sexist cliché

On the other hand, Ms Hassan in Tanzania has earned considerable praise for enacting reforms, including the removal of restrictions on the media, and seeking rapprochement with various opposition parties and figures that had been marginalised, and even threatened, by her predecessor.

Looked at this way, it is a mixed picture; we certainly cannot discern a clear pattern internationally suggesting that having women in the most senior posts leads to better political outcomes. The same seems to be true in our own country. Only a handful of senior female ANC leaders were implicated in state capture allegations, but quite a few have shown themselves to be pretty mediocre cabinet ministers and deputy ministers. It is hard to think of a single one who has put her duty to the country ahead of loyalty to her party; in this, they are no better, or worse, than their male counterparts. The same is broadly true, it must be said, of prominent women in the opposition parties. (I note that my assessment a few years ago was more optimistic in this regard.)

Does all this tell us anything useful? Possibly. On the one hand, maybe it is simply the case that politics is an occupation that attracts people—male or female—who tend to be ego-driven, thick-skinned and ambitious; who are competitive and belligerent by nature. If so, then the stereotypical feminine virtues will not be found very commonly in the halls of political power.

On the other hand, maybe the whole idea of the empathetic, unifying, self-giving female politician is nothing more than a sexist cliché. Maybe those who look for that ‘special touch’ that women supposedly bring to political life are looking for something that doesn’t actually exist.