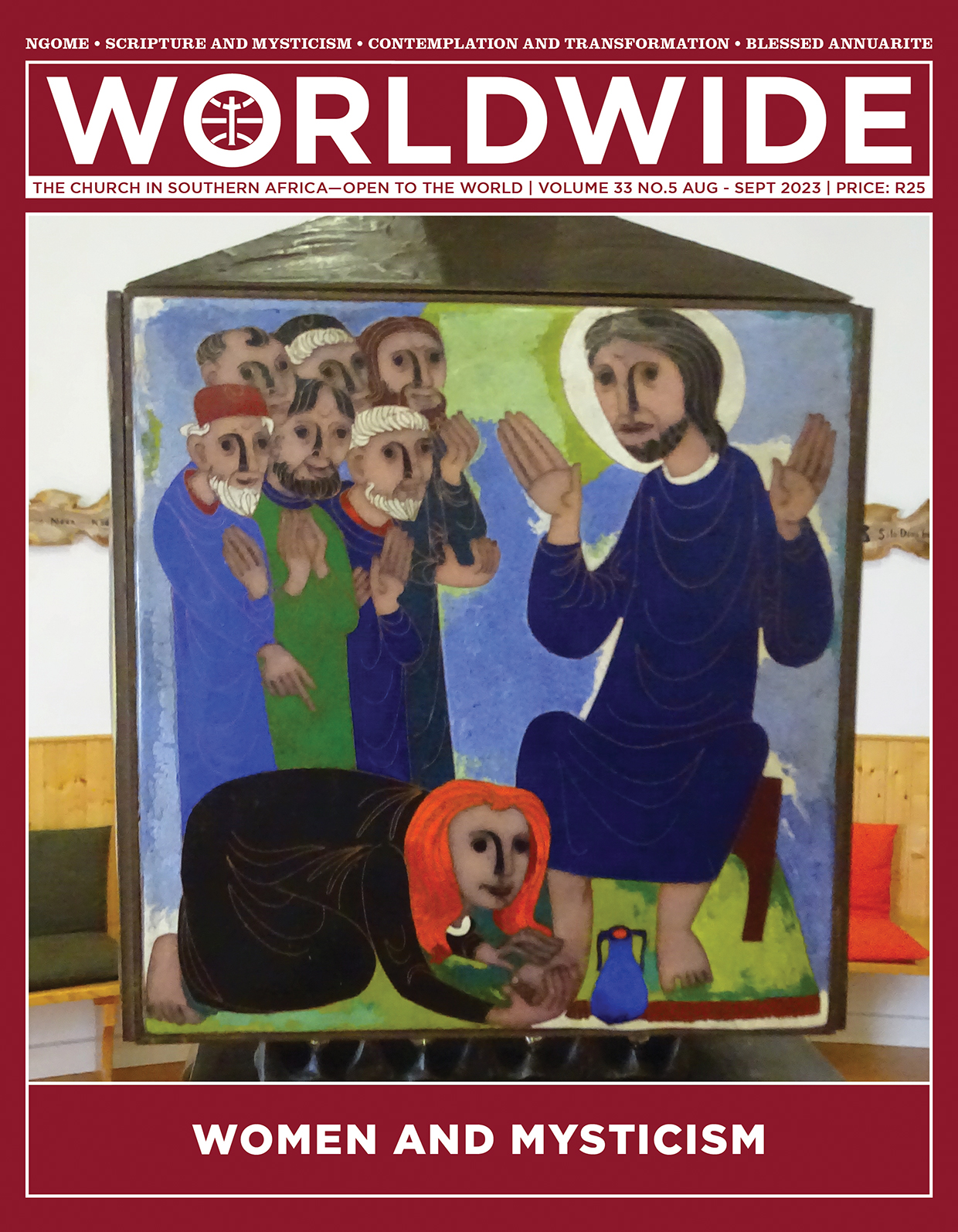

WOMEN AND MYSTICISM

Mary anoints Jesus’ feet at Bethany (John 12:1–8). The scene is part of a series which represents passages of women with a prominent role in the Scripture. The decorations are placed around the sides of the Tabernacle in the Chapel of Meditation at the University of Mystics in Avila, Spain.

Mary listens to and manifests her love for Jesus. Contemplation becomes the mesh in which her Spirit-led actions find their meaning and support.

RADAR

Why the future of the world’s largest religion is female and African

More and more Christians live outside Europe and North America, especially in Africa – and women are central to this shift

BY Gina Zurlo | Co-Director of the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary

I research women in global Christianity and am frequently asked what percentage of the religion is female. The short answer is 52%. But the long answer is more complicated—women form a much more substantial part of Christianity than that number implies.

Headlines about religion may be focused on the words and actions of Western male leaders, but the reality of the church, worldwide, is quite different.

Measuring faith

Social scientists have shown for decades that women are more religious than men by a variety of measures—everything from frequency of private prayer to worship service attendance. Christianity, the world’s largest religion, is no exception. Data from the Pew Research Center 1 show that, compared to Christian men, Christian women are more likely to attend weekly church services (53% versus 46%), pray daily (61% versus 51%), and say religion is important in their lives (68% versus 61%).

It’s not a new trend. In the Gospels, women were the last remaining at the foot of Jesus’s cross and the first at his tomb. Research has shown2 they were critical to the growth of the early church, being more likely to convert to Christianity than men, and most of the early Christian communities were majority female. Throughout history, women were exemplars of the faith as mystics and martyrs, royal women converting their husbands and supporting convents, and founders of denominations and churches that are now all over the world.

What researchers don’t have is comprehensive data on women’s activities in churches, their influence, their leadership or their service. Nor are there comprehensive analyses of Christians’ attitudes around the world about women’s and men’s roles in churches.

“Women, according to an old saying in the Black church, are the backbone of the church,” notes religion and gender scholar Ann Braude3. “The double meaning of this saying is that while the churches would collapse without women, their place is in the background,” behind male leaders. But there’s not much actual data, and without good data, it’s harder to make good decisions.

At the centre of the story

Women are the majority of the church nearly everywhere in the world4, and her future is poised to be shaped by African women, in particular.

Christianity continues its demographic shift to the global south. In 1900, 18% of the world’s Christians lived in Asia, Africa, Latin America and Oceania. Today that figure is 67%, and by 2050, it is projected to be 77%. Africa is home to 27% of the world’s Christians, the largest share in the world, and by 2050, that figure will likely be 39%. United States and Canada were home to just 11% of all Christians in the world in 2020 and will likely drop to 8% by 2050. Furthermore, the median age of Christians in sub-Saharan Africa is just 19.

One of the most common refrains about the church in Africa is that it is majority female. “The church in Africa has a feminine face and owes much of its tremendous growth to the agency of women,” writes Kenyan theologian Philomena Mwaura5.

It’s clear that women have been a crucial part of Christianity’s seismic shift south, including Catholic sisters, who outnumber priests and religious brothers in Africa—and on every continent. Mothers’ Union, an Anglican nonprofit that aims to support marriages and families, has 30 branches in Africa, including at least 60 000 members in Nigeria alone. In Congo, women have advocated for peacebuilding, including through groups like the National Federation of Protestant Women. Next door, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Catholic sisters were at the forefront of providing shelter, education and aid in postwar recovery efforts.

Yet here, too, more precise data about African women’s contributions and religious identities is lacking. Beyond quantitative data, African women’s narratives have often been ignored, to the detriment of public understanding. As African theologians Mercy Amba Oduyoye and Rachel Angogo Kanyoro have stated, “African women theologians have come to realize that as long as men and foreign researchers remain the authorities on culture, rituals, and religion, African women will continue to be spoken of as if they were dead.”