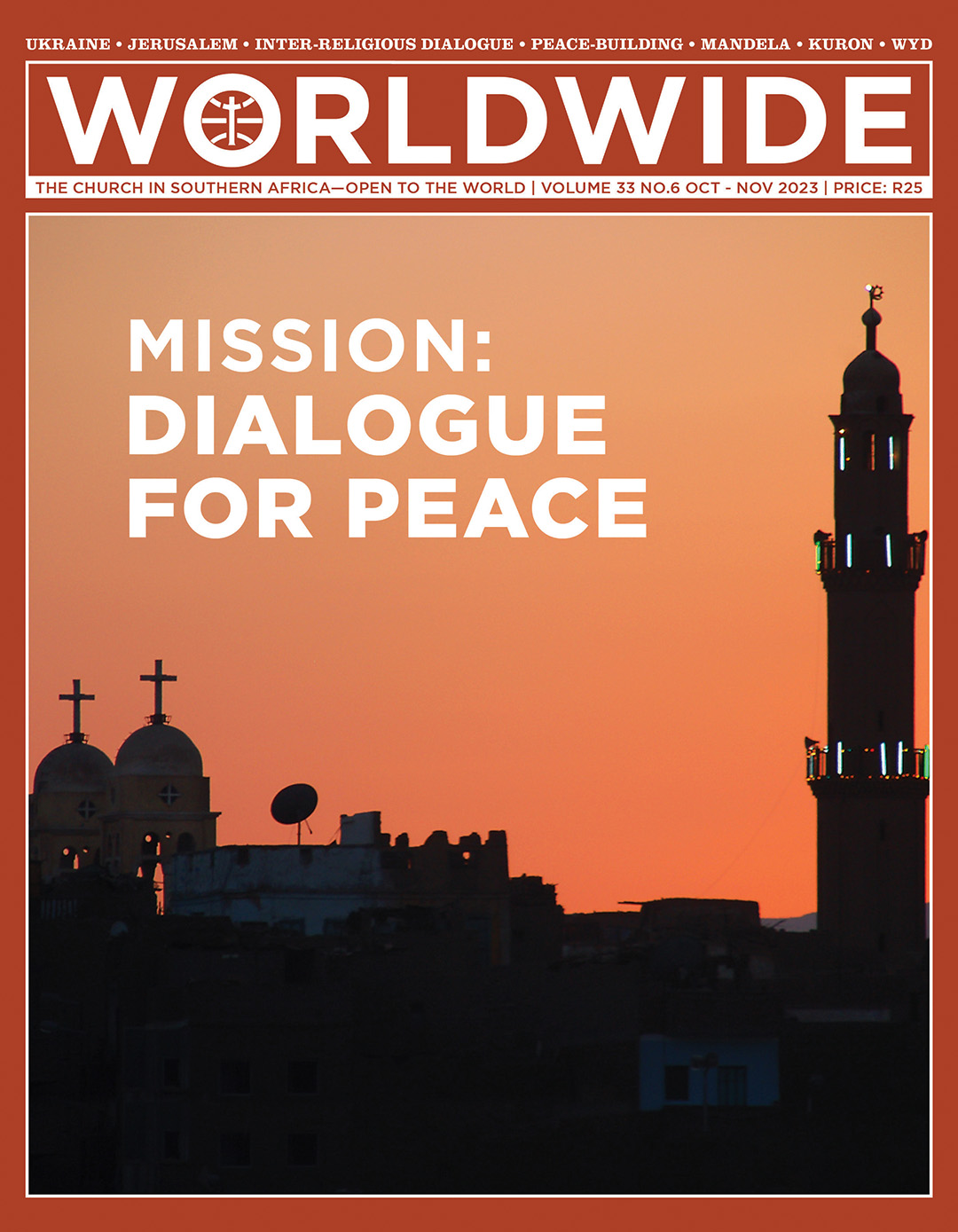

MISSION: DIALOGUE FOR PEACE

The Mosque minarets and church domes of the front cover, facing each other at twilight, transmit a sense of harmony and serenity. The two main religions of the world, Christian and Islam, are called to a mutual understanding and peace-building for the well-being of humanity. The essence of its traditions, far from fundamentalist interpretations, should lead their faithful to pursue together the values of justice and fraternity.

PROFILE • NELSON MANDELA

Dialogue Over Conflict

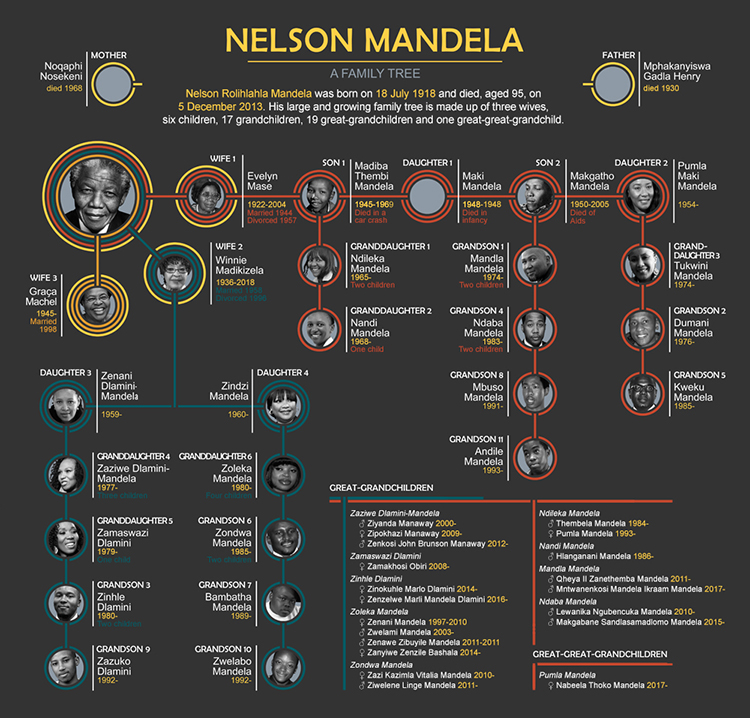

On 5 December 2023 a decade will have elapsed since Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela left this world. Though questioned by some, his figure stands as an inspiring icon for peace-building in the new South Africa. The author weaves together key moments from his life with the dynamics of dialogue.

BY Marian Pallister | Chair of Pax Christi Scotland

YOU MAY be wondering why Worldwide is offering a profile of Nelson Mandela in this issue. Surely this is a man whose story is known, whose life has been celebrated, an international day named for him, his every public and private moment pored over in the most minute detail?

I stand guilty as a white person who continues to lionise Mandela. I live in Scotland, a country that contradicted the then UK Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, when she declared Mandela a terrorist. Glasgow named a square in the city centre while he was still imprisoned on Robben Island. For us he has been, and still is, a hero.

Legacy

In 2023, however, younger generations in South Africa are questioning Nelson Mandela’s legacy. Did his skills in dialogue really do more harm than good for the generations who would follow him?

Is the Rainbow Nation, that Mandela strove to create, really past its sell-by date, as South African writer and political commentator Sisonke Msimang suggests? Perhaps instead it is the universal economic and environmental crises that people are facing that have skewed the focus Mandela gave to his country and to the world.

Surely there has never been a greater need for the unity he endeavoured to create—a unity that, some say, the up-and-coming generation in South Africa believe was a trade-off for justice.

Retribution and reconciliation

There is an emphasis today on the small number of people brought to justice for the crimes committed during apartheid. But ‘justice’ is not about prison sentences, not simply a matter of punishment. Dictionaries tell us that justice is fairness in the way that people are treated; the Bible tells us that God enters into dialogue with offenders, leading to forgiveness rather than punishment.

Mandela’s dialogue skills raised his profile in the world, and the profile of the campaign to end apartheid

With his strong grounding in the Methodist teaching, he received at school and college, Mandela perhaps took his lead from those Old Testament stories that sought not to punish, but to reconcile. Mandela surely knew better than anyone, that it takes a lot more effort to reconcile offenders than to stick them in jail.

Values learnt at home

He grew up understanding that dialogue was all-important. He learnt this from his father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, a chief of the Themba people, who are part of the Xhosa nation. Xhosa traditions laid the foundations for Mandela’s ability and inclination to dialogue.

Today’s South African needs no reminder that in the early part of the 20th century, there was no dialogue between Black people and the White rulers of the day. Being a chief gave Mandela’s father no privileges—indeed, the colonial officials in Transkei disrespected the role, and so when there was a dispute with a local white magistrate, the family’s lands were confiscated. The only reason Mandela could attend school was because his mother, Nosekeni, was friendly with a Methodist minister who saw the boy’s potential.

He was just nine when his father died of a chest infection. He was then sent to live in the care of Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo, and it was there he began to learn in earnest about fairness, equality, leadership and justice, and to witness the “dialogue” that he grew up to value. Local chiefs and village headmen attended the tribal councils that his guardian held, each having their say until consensus was reached. The boy sat in on these, listening and learning.

He would explain as an adult that majority rule was not part of his tribal culture and so, in his own leadership, he liked to listen to all points of view before giving an opinion. Those traditions offer lessons to “Western” concepts of democracy, which to a great extent have failed us.

His culture remained important to Mandela throughout his life.

University stage

And of course, the reconciliatory Mandela, who is now criticised for being over-generous to those who led the apartheid government, understood, as a student, that while he would be the first in his tribe to achieve a university degree, he was not able to choose his future in the way white South Africans could. He studied at the only tertiary education establishment for Blacks, the University College at Fort Hare, seeing his future as a clerk or an interpreter – typical jobs then for educated Blacks.

The African National Conference (ANC) became part of his life at this point, although he was not yet exposed to the extreme harassment and violence others experienced. His circumstances led him, however, to meet those who would share his future and the future of South Africa.

Life in Johannesburg

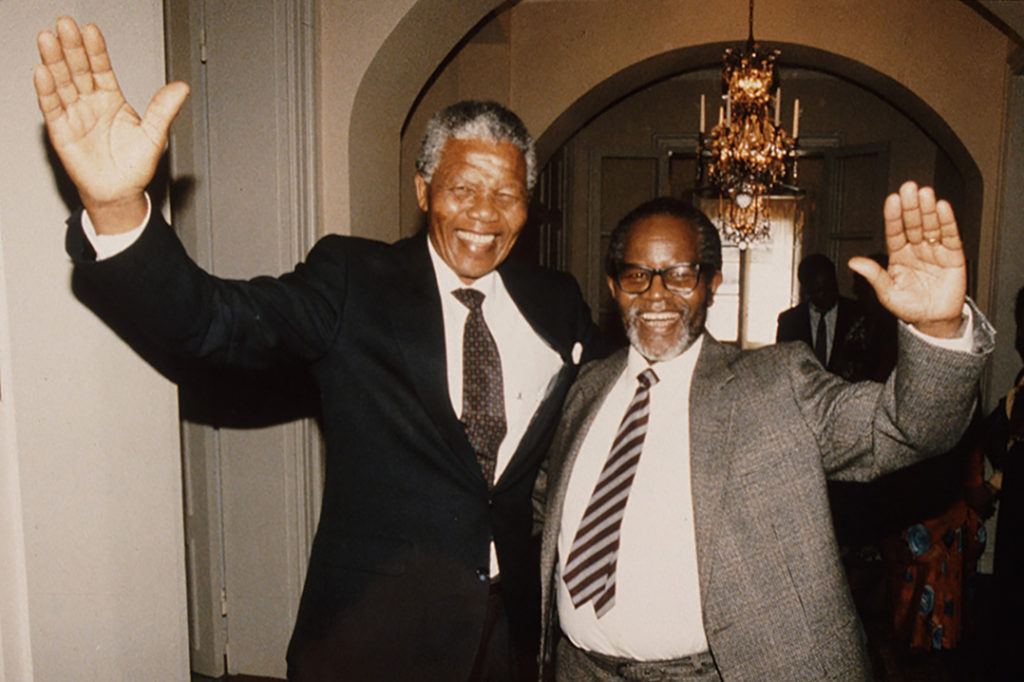

Mandela ran away from an arranged marriage and ended up working as a night watchman in a Johannesburg mine. The chances of a degree and a good future seemed to have been thrown away, but a young Black estate agent named Walter Sisulu introduced Mandela to a white lawyer, Lazar Sidelsky, who was persuaded to take him on as a trainee. He did eventually achieve a degree, but for now he was learning the harsh realities of living under the repressive regime—and that rural poverty was very different from the poverty and violent police harassment experienced in black areas of Johannesburg such as Alexandra.

Mandela would say “I learned more about poverty in that first year [in Johannesburg] than I did in all my childhood in Qunu.”

He also learned more about segregation than he had previously been exposed to. When he began his law studies at the University of Witwatersrand, there were whites who ostentatiously displayed their contempt for him in lecture rooms. There were also, however, whites who would join his struggle for freedom: Joe Slovo, Ruth First (who married Slovo), George Bizos and Bram Fischer became as well-known as Mandela himself, as they came together to work for freedom from apartheid.

World renown for righteousness

The next stage in his life is so well documented that it needs no re-telling, but it is worth remembering how Mandela’s dialogue skills raised his profile in the world, and the profile of the campaign to end apartheid. We boycotted South African produce in the Northern Hemisphere because of the words we heard that exposed the apartheid regime. We denied that “terrorism” label and yes, “lionised” Mandela because we learned that his negotiating skills could make a difference. He made sense.

Surely there has never been a greater need for the unity Mandela endeavoured to create

His words were literally smuggled out of South Africa, so that in 1962 when Mandela conducted his own defence in a Pretoria courtroom, where he stood accused of inciting people to strike and of leaving the country without a valid passport, a young generation in Scotland was stirred to feel passionate on behalf of their Black brothers and sisters at the other end of their common home.

The magistrate questioned what Mandela’s argument had to do with the case in hand. For us, his words were inspirational:

“I feel oppressed by the atmosphere of white domination that lurks all around in this courtroom. Somehow this atmosphere calls to mind the inhuman injustices caused to my people outside this courtroom by this same white domination.

“It reminds me that I am voteless because there is a parliament in this country that is white-controlled. I am without land because the white minority has taken a lion’s share of my country and forced me to occupy poverty-stricken reserves, over-populated and over-stocked. We are ravaged by starvation and disease . . .”

Peace-builder for a new South Africa

His negotiating skills in the Rivonia case earned him decades on Robben Island rather than a death sentence. We know that within that cruel prison system he dialogued with prison guards as well as — in time and in secret — politicians. He emerged from that to seek to establish the Rainbow Nation that is now denigrated by some in a generation who wish to give Mandela feet of clay.

Time and again it is his role in the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) talks, that is blamed for the situation in South Africa in 2023. The first CODESA began in 1991 at the Johannesburg World Trade Centre and failed as violence continued throughout the country — violence that Mandela believed was government supported. He had a greater role in CODESA II and his negotiating skills helped achieve the liberal constitution that provided for three branches of government, an independent judiciary, and a bill of rights protecting individual human and property rights. This new South Africa was to be a parliamentary democracy based on one man, one vote. There would be no white veto of any sort, and no “group rights.” For five years, there would be a transitional government in which all significant political parties would be represented. Thereafter, a government would be formed on the basis of majority rule.

Set-backs and controversies

Then came the Truth and Reconciliation process, which Mandela’s former wife Winnie has called “a charade”. In today’s South Africa there are those who say that “reconciliation” let too many people off the hook.

But mostly it is 2023’s economic situation that is leading young South African’s to question Mandela’s legacy. Inequality and economic hardship persist. Did the country’s first Black president do enough to emancipate black people economically?

There were boom years after apartheid, but in recent years, there has been an economic slump. This pattern is not confined to South Africa and cannot really be laid at the feet (clay or otherwise) of Mandela. Perhaps the greatest mistake was to allow more than 70% of arable land to remain in the ownership of white farmers, who make up less than 10% of the population: the “lion’s share”.

His negotiating skills in the Rivonia case earned him decades on Robben Island rather than a death sentence

Nelson Mandela is a name that will continue to resonate in South Africa and around the world. It is a name associated with negotiation, with influential dialogue, but it is right to concede that no man can get it right all of the time. It is perhaps well to remember that Mandela was head of state for one term and officially retired from public life in 2004. His legacy may be flawed, but he surely cannot be blamed for all that has happened in the intervening two decades.

He died at the age of 95 on 5 December 2013. If there must be blame for the state of the nation ten years on, wouldn’t it be wise to take a leaf from Mandela’s book and listen to all voices before making decisions?