MISSION: DIALOGUE FOR PEACE

The Mosque minarets and church domes of the front cover, facing each other at twilight, transmit a sense of harmony and serenity. The two main religions of the world, Christian and Islam, are called to a mutual understanding and peace-building for the well-being of humanity. The essence of its traditions, far from fundamentalist interpretations, should lead their faithful to pursue together the values of justice and fraternity.

FRONTIERS • KURON PEACE VILLAGE

Former Enemies in a Haven of Peace

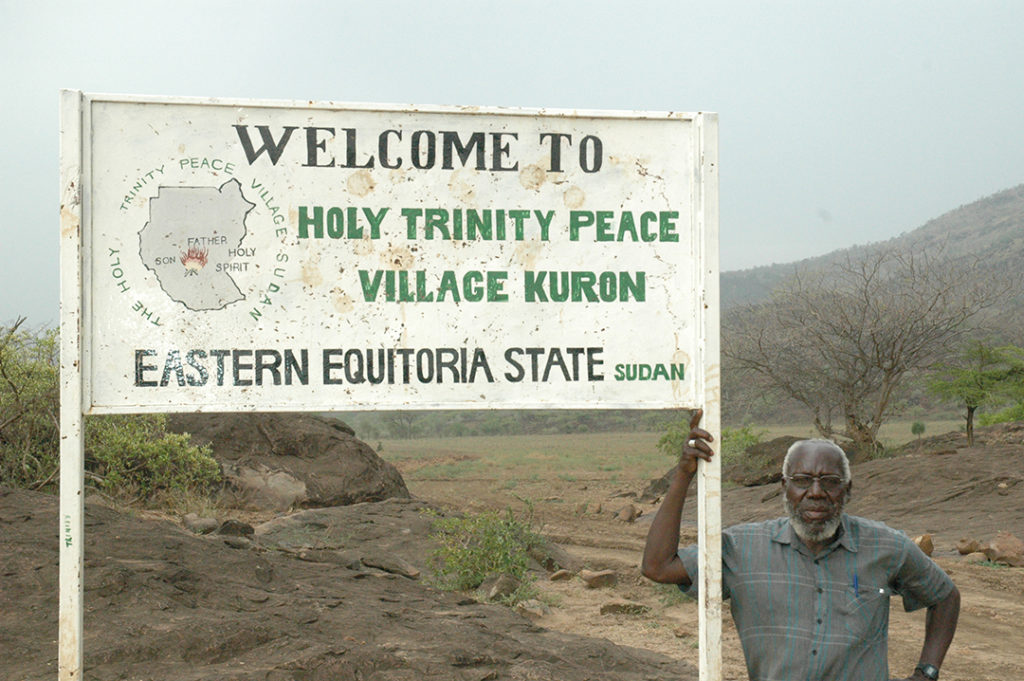

Mons. Paride Taban, Bishop Emeritus of Torit initiated, in 2004, a Peace Village on the banks of the Kuron River, a hilly area of Southern Sudan where different ethnic groups of pastoralists live side by side. Dedicated to the Trinity as a perfect symbol of communion, the village aims to be a focus of hope, peace and reconciliation for a land whose social fabric has been destroyed by the armed conflict and discrimination.

BY ALBERTO EISMAN, JOURNALIST | NAIROBI, KENYA

ON A hill near the road leading from Jerusalem to Tel-Aviv there is a community called Neve Shalom/ Wahat as-Salaam (“Oasis of Peace” in Hebrew and Arabic). This unique community has a cooperative, school, farms, guesthouse and a meeting centre. It is made up of about 50 families of Jewish and Palestinian backgrounds who for years have decided to live together in the same place in a peaceful manner despite the on-going bloody conflict between Israel and the Palestinian population.

Through cooperative work, education (they have the first bilingual school in the region), and promoting values such as respect and mutual appreciation, this community wants to overcome the barriers of mistrust, prejudice and hatred which have been built up over the years and its historical vicissitudes.

Bishop Paride Tabán visited the “Oasis of Peace” community in 1993 and in 1999. The vision of this peculiar group, made up of enemy populations engaged in a bloody confrontation, left in the Sudanese bishop an unparalleled impression manifesting the power of love, respect and mutual acceptance as a means to heal the wounds of war, violence and hatred.

Bishop Taban had gone to the Holy Land seeking a well-deserved rest from long and dramatic years of service in his troubled country and fate destiny brought him a providential encounter with the members of “Oasis of Peace”, a milestone in his life. The testimony of the peaceful coexistence of these people led him to make a resolution for his life: to start a similar community in Sudan on the day of his episcopal retirement.

On the banks of Kuron

After years of pastoral work, different responsibilities—he was founder and president of the New Sudan Council of Churches—and his continued involvement in different peace activities, Bishop Taban asked the Pope for his retirement before he was even of canonical age to do so. John Paul II accepted it in 2004. Inspired by that Jewish-Arab community, immediately his dream began to take shape. Already in 2003, on his twentieth anniversary as bishop of Torit, Mgr Taban had already made a geographical recognition of a vast area, very close to the border with Ethiopia belonging to the region of Eastern Equatoria in Southern Sudan. He then, after assessing different possibilities in the region, he decided to start his “peace village” on one of the banks of the Kuron River, a hilly area around which there are different ethnicities of herders (toposa, murle, jie, kachipo, buya, nyangatom, etc.). These groups, among other things, are famous for the fact that they plunder the livestock of their neighbours, also pastoralist tribes.

Cattle rustling is a tradition that goes back to the ancestral myths of the pastoral tribes inhabiting the vast Rift Valley. According to their ancient cosmogonic tales, when God created the world, He gave each human group a different “field of action”. To some tribes He gave the rivers to fish, to others the fields to grow crops, and to the shepherds he gave the livestock. Accordingly, all the livestock on the face of the earth is considered as rightfully belonging to them and it is therefore their duty to return it to its rightful owners “by divine decree” (even if they have to take them away from other herding tribes related to them).

Mgr Taban decided to start his “peace village” on one of the banks of the Kuron River, a hilly area around which there are different ethnicities of herders

The plundering of cattle has been a “rite of passage” that, through bravery and courage, invested the younger ones into the rank of adult warriors. A few decades ago these skirmishes were not too bloody because they were perpetrated with mere throwing weapons (bows, arrows and spears), but the modern and fulminating proliferation of light weapons -especially the ubiquitous Russian Kalashnikov rifle- has meant that this practice has progressively been turned into a veritable butchery sowing death and destruction in large parts of the region.

Slow work

According to Bishop Tabán, this bloody custom can only be overcome when the different ethnic groups live and grow together. It is not something that can be changed overnight, but through a slow work that will last for generations. So far, the new members of each tribe live without interacting with other ethnic groups and this is how prejudice, ignorance and hatred grow over the years.

Only if the new generations are able to live, learn, play and grow up together will they be able to build a new society with renewed values of coexistence. It is here that the “Peace Village of Kuron” has set its most ambitious goal and, having been erected on a border between different tribes, wants to be a centre bringing together ethnicities where the following services are offered to the different communities:

Primary school is a means for the personal and intellectual growth of children, among whom the female population is undoubtedly the one which suffers the most from the backwardness and lack of access to this type of services. Not a single tribal girl in the area has been able to go to university, which shows how neglected these populations have been for years.

The school provides an ideal environment for mutual trust and in-depth knowledge beyond clichés and ethnic barriers or prejudices, while promoting dialogue among young people and addressing the deeper roots of the problem of violence associated with cattle ownership.

The dispensary offers primary health care to a community that has largely never seen a doctor or nurse and whose health situation is badly affected by various diseases resulting from poor sanitation, lack of knowledge of basic human and animal hygiene and lack of access to the most basic medicines. The meeting centre is an open space for social and peace-promoting activities. It brings together traditional chiefs and representatives of different social groups to dialogue and discuss issues related to their way of life, as well as how to solve ancestral problems and the enmity resulting from cattle raids. It is also a meeting point for young people who choose sport as a substitute for violent confrontation.

People have started to practice agriculture; before they were moving all over the place, but now they have accepted new ideas and are carrying out good agricultural practices

Finally, the agricultural project aims to promote local tribes to become self-sufficient in food production and thus make their main livelihoods less dependent on livestock, which as we have seen is often a source of rivalry and armed confrontation.

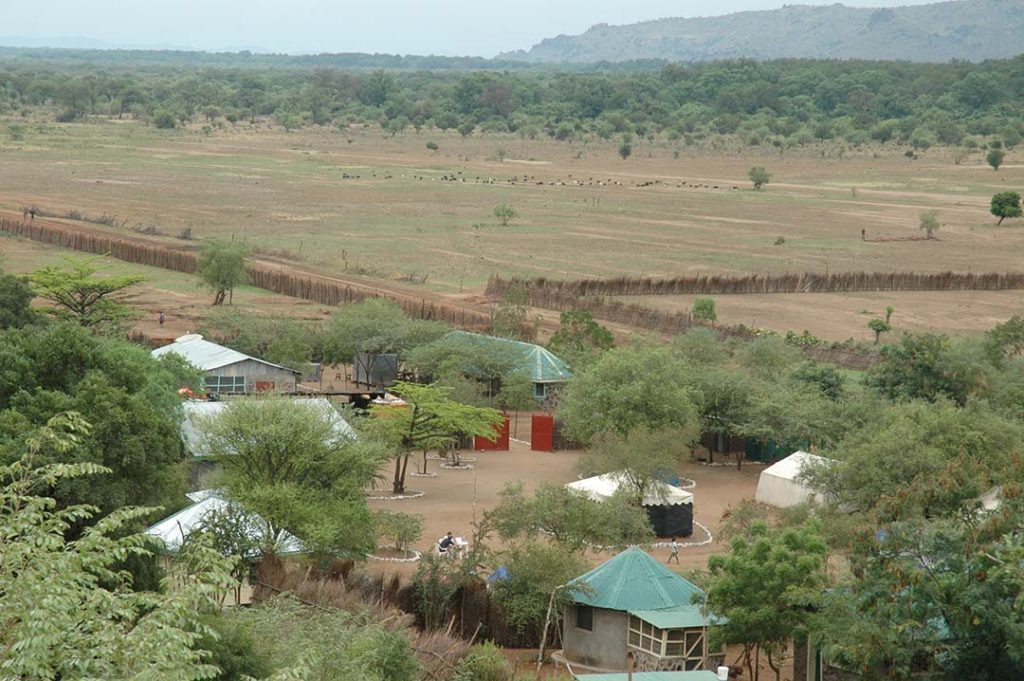

So far, this initiative has been a great success. People who visit the village to participate in any of its activities have the opportunity to learn basic agricultural techniques, to see in the “pilot fields” how new crops can be introduced, and even receive seeds or seedlings to start a vegetable garden or a field of their own. The fertile fields surrounding the village are a testament to the barely exploited fertility of this land and the great potential it has to enable the tribes living there to subsist without hunger or food shortages.

Great impact on the region

To carry out his project, Bishop Taban surrounded himself with people from different professional and ethnic backgrounds: teachers, agronomists, health workers, volunteers. Thanks to all these people and the financial support of various international groups and organisations, that abstract inspiration in the Holy Land has materialised in the real life of a Sudan also ravaged by violence, intolerance and isolation.

Andi Alfred is one of the people who has worked the longest on the “Kuron Peace Village”. In his opinion, this initiative has had a great impact on the region:

“I have seen many changes since we started the village. Now there are many people living around here; especially a lot of children when a few years ago no one lived here. Another big change is that people have started to practice agriculture; before they were moving all over the place, but now they have accepted new ideas and are carrying out good agricultural practices”.

Bishop Tabán’s decision to retire to a remote and isolated region has not been without criticism. Some had hoped that he would use his international reputation as a peacemaker to attract large-scale funding for much more ambitious development projects in the region. He, however, while aware of the misgivings that his work may create, still sees it as a justified and worthwhile cause, to the point of wanting to spend the last years of his life on it.

Many of these enterprises run the risk of being eclipsed when their founders disappear. It is precisely for this reason that Bishop Tabán wanted to found his work in a spirit of self-sufficiency, so that the community can then continue its work without depending on external support.

Andi acknowledges that, at the beginning, this was only the dream of one individual, “but now this has changed. Now we all share his vision and we are implementing it. People will continue to work even after the day when the bishop is no longer with us”.

In the same way that the Neve Shalom community has become a focal point for peace-making efforts in the Middle East, the Kuron Peace Village dedicated to the Trinity as the perfect symbol of the community is intended to be a focus of hope, peace and reconciliation for a land that has suffered massively from the effects of violence, forced displacement and intolerance, and whose social fabric has been destroyed over long years of armed conflict and discrimination.

Indeed, it seems that life around the village is beginning to change: some time ago, members of other tribes never ventured into this area for fear of attacks by cattle raiders; now that atmosphere of fear has disappeared and people of different ethnicities are beginning to live together in the village without discrimination or threat. A powerful seed of reconciliation and peace has just been sown in Southern Sudan.