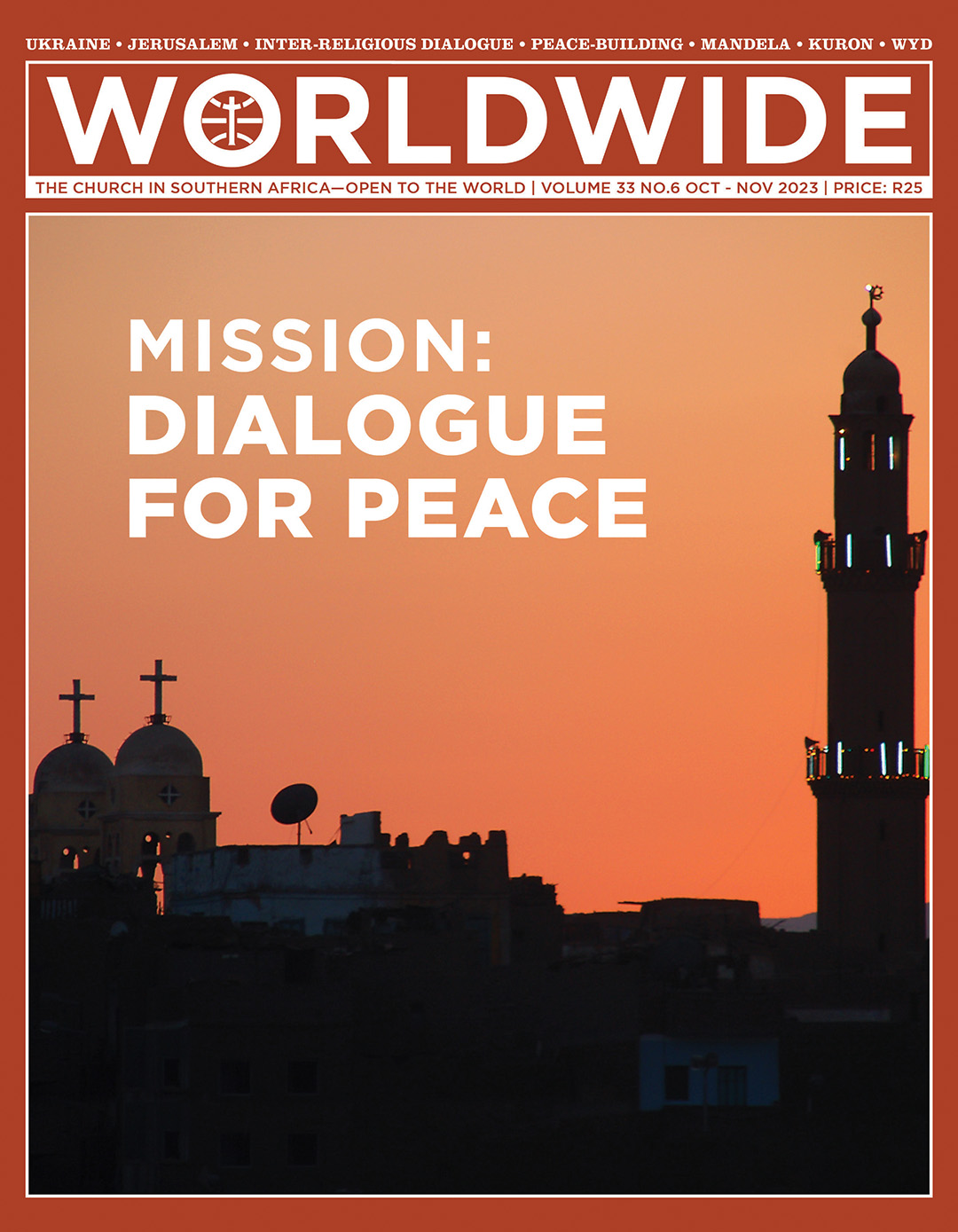

MISSION: DIALOGUE FOR PEACE

The Mosque minarets and church domes of the front cover, facing each other at twilight, transmit a sense of harmony and serenity. The two main religions of the world, Christian and Islam, are called to a mutual understanding and peace-building for the well-being of humanity. The essence of its traditions, far from fundamentalist interpretations, should lead their faithful to pursue together the values of justice and fraternity.

FEATURES • INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE

“INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE OR SOLIDARITY PLAYED A MAJOR ROLE IN UNITING THE OPPRESSED COMMUNITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA”

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND, ENGAGED WITH DR A. RASHIED OMAR* ON ASPECTS OF INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE

What role has interreligious dialogue played in your own life?

Interreligious Dialogue has played a significant role in my personal life, religious ministry and civic leadership. I have been active in interreligious activities for over three decades and it would not be an exaggeration to say that interreligious solidarity has shaped my Islamic theology and Muslim praxis profoundly.

In the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, as a young Imam at the Claremont Main Road Mosque, in Cape Town, I became inspired and active in interreligious activities through the South African Chapter of the World Conference on Religion and Peace (WCRP-SA), which was founded by Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 1984.

As a beneficiary of South Africa’s rich and robust interreligious solidarity movement, I believe that through my indefatigable passion for interfaith activities, I am not merely honouring, but also giving, profound thanks to the rich and diverse interreligious legacy bequeathed to us by Archbishop Tutu. He was for me the embodiment of interreligious solidarity.

What role do you think dialogue and interreligious dialogue have played in the past and present in South Africa?

Interreligious dialogue or solidarity played a major role in uniting the oppressed communities in South Africa in their struggle against the apartheid regime. South Africa has a unique and unparalleled interreligious solidarity movement, thanks in large measure to the wise leadership and sterling contributions of Archbishop Tutu.

Fratelli Tutti is already creating a robust debate among “just war” theorists and peacebuilding activists within the Catholic Church

In 1986 with his appointment as Archbishop of Cape Town, Tutu transformed St George’s Cathedral into what became known as “the people’s church”. Under his leadership, the cathedral emerged as a centre for interfaith mobilisation against apartheid in the Cape Town. People from all faiths and none, found inspiration and comfort in the cathedral in their struggle against the evil and oppressive apartheid system.

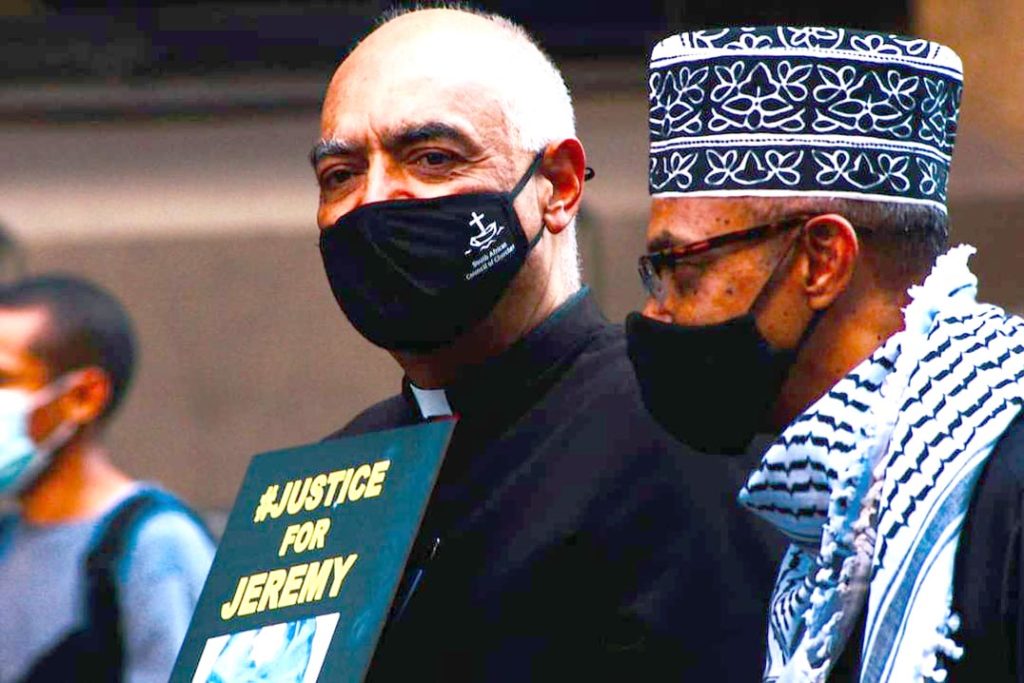

On 13 September 1989, Archbishop Tutu led one of South Africa’s largest mass interreligious processions through the streets of Cape Town that symbolically announced the “reclaiming of the city’. Along with Archbishop Tutu, the Reverend Allan Boesak and Shaikh Nazeem Mohamed, the leader of the Muslim Judicial Council, were at the head of that march. Thousands of Cape Townians were brought together representing people of all faiths and none, all united in a common struggle against a common enemy—apartheid. Those days can be recalled as the beginning of the end of apartheid in South Africa.

Since its inception in 1994, interfaith prayers have consistently inaugurated the proceedings of South Africa’s non-racial and democratic parliament.

You work in the US – what would you say about the welcome such dialogue receives there?

For interreligious activists who have long campaigned that interreligious dialogue and solidarity should be accorded a more prominent place in the programmes of religious institutions in the United States, the irony of the post September 11, 2001 terror attacks in America is that interreligious activities have ascended to near the top of the agenda of a number of religious institutions.

How does one explain this “counterintuitive reality”? How does one account for the fact that in the midst of the worst kind of religious bigotry, people of different faith traditions can also find solace and healing through interreligious solidarity? The answer, I contend, vividly illustrates the ambivalent role of religion in conflict, violence and peacebuilding. For while on the one hand religion has and continues to be implicated in situations of deadly conflict, on the other, it continues to provide hope and sustenance in the face of the worst kinds of indignity and human suffering. This contradictory role of religion in conflict can occur almost simultaneously.

Fratelli Tutti is compelling mainstream Islamic scholars to engage more seriously with the innovative viewpoints of Muslim peacebuilding scholars

The critical challenge facing interreligious advocates in the US, however, is how to sustain and transform this renewed interreligious solidarity and energy into a powerful grassroots interreligious movement for peace and justice.

You have said of Pope Francis’s encyclical Fratelli Tutti (All Brothers and Sisters) that it ‘marks a big step forward in promoting interreligious dialogue and peacebuilding’. Could you relate that to South Africa, and perhaps elsewhere in the world?

Fratelli Tutti has given an important theological rationale and legitimacy to the burgeoning interreligious movement in South Africa and elsewhere in the world. It has galvanized Catholics and people of other faiths who may have been on the margins to become even more committed to interreligious peacebuilding.

In South Africa, for example, Fratelli Tutti and Pope Francis’s subsequent meeting with Grand Ayatollah Sistani in Iraq, has led to the formation of a new interfaith body, Platform for Theological Dialogue and Practical Ethics, replicated in many other parts of the world.

Fratelli Tutti is already creating a robust debate among “just war” theorists and peacebuilding activists within the Catholic Church. Within Muslim circles, Fratelli Tutti’s challenge is even more controversial. Only a handful of Muslim scholars have proposed an Islamic theology of nonviolence, such as Maulana Wahiduddin Khan of India, Shaykh Jawdat Sa`id of Syria, Chiawat Satha-Anand from Thailand and the Muslim Peace Fellowship in the US. Fratelli Tutti is compelling mainstream Islamic scholars to engage more seriously with the innovative viewpoints of these Muslim peacebuilding scholars.

Elsewhere I have suggested that the Catholic Church convene a robust and sustained interreligious dialogue on Fratelli Tutti’s call for prioritising non-violent direct action and challenging the traditional parameters of the “Just War Theory” as morally indefensible given the destructive and indiscriminate nature of modern-day weapons of mass destruction.

How significant in the Muslim world was that co-signing with Ahmad al-Tayyeb of the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together?

It was highly significant, marking a big step forward in promoting interreligious dialogue and peacebuilding, especially between Catholics and Muslims.

After the signing of the Document in 2019 a special interreligious committee was formed to continue to promote the principles of tolerance enshrined in the document globally. Since then a number of global meetings on tolerance have been sponsored by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and its programmes were well received by the established religious as well as the United Nations.

It is my considered view, however, that the Document of Human Fraternity forms an integral part of the soft power strategies employed by the ruling monarchy of the UAE to mollify the democratic aspirations of its own citizens and those of disenfranchised and oppressed peoples of the Middle East.

Many of today’s youth perspectives for launching more just and compassionate societies are challenging established views and strategies

Human Rights Groups have raised questions about this latest UAE initiative. Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East executive director of Human Rights Watch, has argued: “The papal visit was being used to conceal the same moral rot that has afflicted the Gulf for decades.” She furthermore claimed: “The Emirates still deprives residents of basic rights, including rights of free worship and expression. It persecutes peaceful critics, political dissidents, and human rights activists.”

While championing narrow religious tolerance, the Emirati’s embrace of narrow religious freedom does not extend to open political expression and democratic representation for citizens within their own country.

Moreover, the dubious UAE role in abetting and supporting deadly conflicts in Yemen, Syria, Libya and Bahrain, which arose in the wake of the Arab Spring, belies their claim to be credible protagonists of sustainable peace in the Middle East and among Muslims globally.

Notwithstanding the short-term successes of these soft power strategies in preserving the status quo, in the medium to long term it is ill fated.

Unless despotism, one of the root causes of deadly conflict in the Middle East, is not adequately addressed, sustainable peace and genuine religious freedom will continue to elude all the people of the Middle East, including its Christian minorities.

The best strategy in the Middle East is to strive for greater levels of interreligious solidarity in the struggle for social justice. Genuine religious freedom does not occur in isolation, but arises from within, and out of concomitant struggles for socio-political justice and comprehensive human rights and dignity for all. Interreligious peace builders in the Middle East could best render their struggles for religious freedom and full citizenship as an intersectional struggle for social justice that links religious freedom to the quest for comprehensive human rights and dignity for all.

However, to ensure that such a programme of action procures positive and sustainable peace there, it is critical that it should be initiated, sponsored and led by local actors and institutions.

Notwithstanding its flaws and weaknesses, Shaykh al-Azhar and Pope Francis have inaugurated through the Document of Human Fraternity a platform for a more constructive interreligious dialogue between Muslim leaders and Catholics leading to a just peace in our contemporary world. If this interreligious conversation could be located within the broader framework of Pope Francis’ theology of compassion for the poor and his prophetic theology of speaking truth to power, interreligious dialogue will find even greater resonance among Muslims.

Is there a different dialogue that all religions must seek to have with our young people?

As a student leader in the anti-apartheid movement in 1976 I recall how painful it was to be disparaged by elders that I loved and respected because they thought our anti-apartheid activism was disrupting the status quo and the negative peace of our society. Similarly, many of today’s youth perspectives for launching more just and compassionate societies are challenging established views and strategies. This is causing intergenerational tension and conflict, but that should be welcomed and nurtured to allow for more robust debate. One creative way of dealing with such intergenerational conflict is to enable a safe space for dialogue and debate. We need to listen to each other with both generosity and sincerity to actively hear “the other”, and to recognise that the context between generations is very different. Finally, we need to embrace and be open to both the strengths and weaknesses of our respective struggles. By doing so, we will have greater opportunities to find each other. I am honoured to serve as an advisor to Arigatou International, a global interreligious body whose aim is to nurture interreligious dialogue and solidarity among children. Sponsored by a Japanese Buddhist group, its pioneering work is creating a new generation of interreligious activists.

Dr A. Rashied Omar, associate teaching professor of Islamic studies and peace-building at the Kroc Institute for International Studies of the University of Notre Dame in the US. He is also a fellow of the Keough School’s Pulte Institute for Global Development in Cape Town, where he is field research advisor to Master of Global Affairs students. He also serves as Imam at the Claremont Main Road Mosque, Cape Town. He is a trustee of the Healing of Memories Institute in South Africa, a member of the Interfaith Council for Ethics Education with the Japanese NGO Arigatou International, and an advisory board member for Critical Investigations into Humanitaria