MISSION: DIALOGUE FOR PEACE

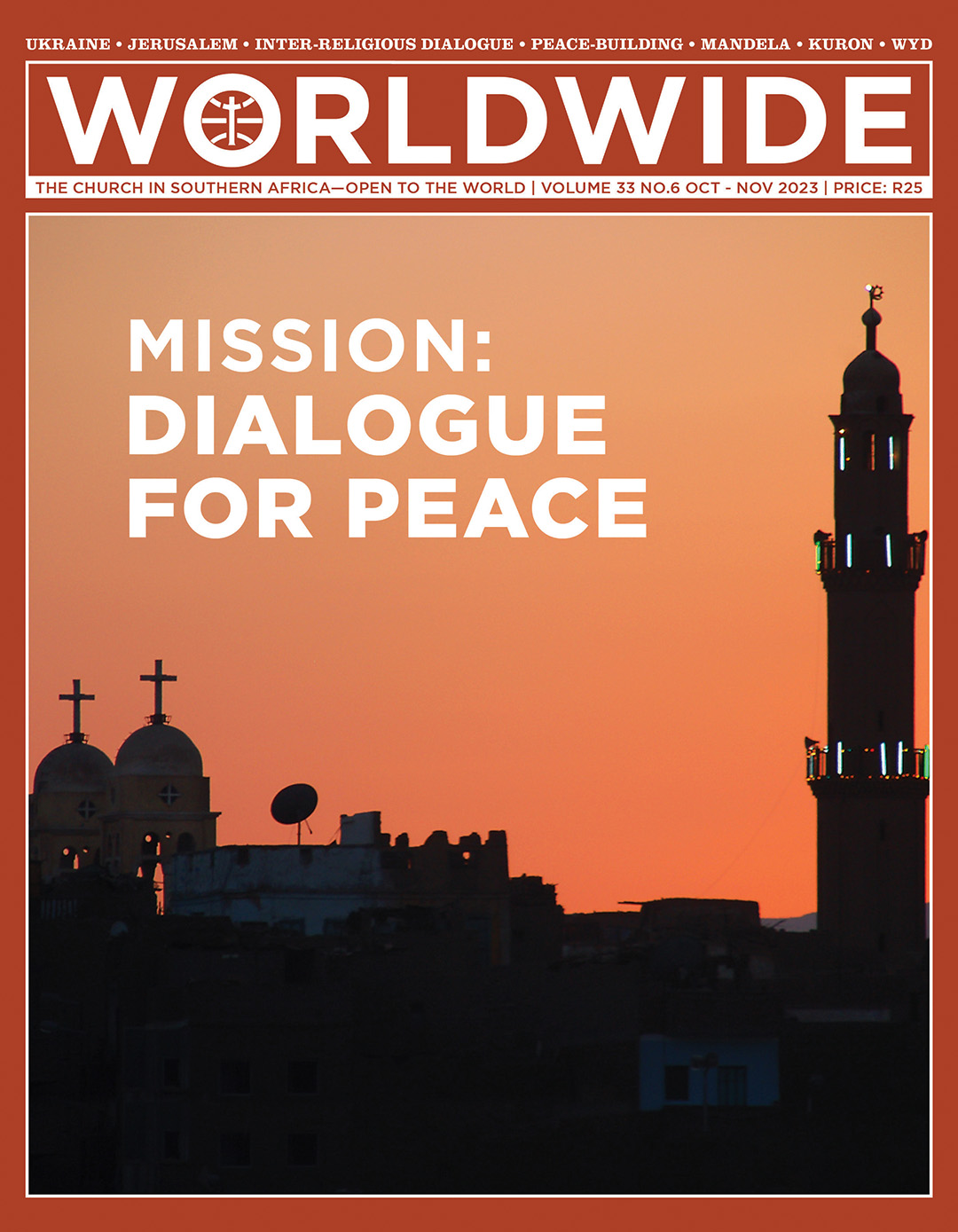

The Mosque minarets and church domes of the front cover, facing each other at twilight, transmit a sense of harmony and serenity. The two main religions of the world, Christian and Islam, are called to a mutual understanding and peace-building for the well-being of humanity. The essence of its traditions, far from fundamentalist interpretations, should lead their faithful to pursue together the values of justice and fraternity.

SPECIAL REPORT • INTERFAITH DIALOGUE

The Longing for Justice and Peace with Muslim and Jewish Friends

The covenant between God and Abraham reveals a common faith foundation for Jews, Muslims and Christians. Their shared ground of belief should lead, according to the author, the living out of ethical values of harmony and dialogue towards the building of God’s kingdom.

BY Sr. Anna Maria Sgaramella CMS, Prof. Salesian Theological Seminary & Franciscan Studium Jerosolamitano | Jerusalem

IN JERUSALEM, interfaith encounter is part of daily experience. It shapes not only the culture of friendly or conflictive encounter, but also the way of believing. In Jerusalem, and the rest of the world, Christians are called to engage in dialogue with believers of other faith traditions. We may wonder how the interfaith relationship among Jews, Christians and Muslims mirrors God’s reality of the One and Unifying God Whom the practisers of these monotheistic religions believed in.

What might the common ground of encounter be among them? What common ethical word of commitment make these communities implement the Shalom, where wasatia (moderation) expresses harmony in diversity? To answer these questions, we undertake the following reflection which intends to consider the mission of the three communities: Israel, Church and Ummah (Muslim community). We do so in the light of the words of the prophet, “What is good has been explained to you, man; this is what Yahweh asks of you, only this: to act justly, to love tenderly and to walk humbly with your God”. (Micah 6:8).

The Mission of Israel: “Be a Light among the Nations” for the National and Universal Kingdom

As a Christian living in Jerusalem, with Jewish and Muslim friends, my experience of dialogue is derived from a dialogue of life with our neighbours; monthly spiritual gatherings, praying together, and engaging in theological dialogue within Elijah Interfaith Theological Institute. While we enrich our faith through the knowledge of the others’ faith, the question about the mission of each community makes us aware of the common responsibility in building a society where there is respect for the human rights of all.

among Muslims, Jews, Christians, Palestinians, and Israelites

In the Jewish tradition, it is in the covenant with Yahweh, that Israel receives her mission. Yahweh appoints His servant Israel as a “light of the nations” (Is 42:6). According to the Abrahamic promise, in Israel, the blessings are for all peoples. The interfaith reflection leads us to see the believers as being called to build the kingdom of God. In rabbinic theology, it is viewed as the visible/ invisible kingdom of God. The invisible kingdom is mainly spiritual, related to attitudes of mind, and commitment at the individual level. This is proclaimed in the ‘Shema’, which declares that God is King in all the four corners of the world.

The responsibility for the life of all leads to the ethical commitment for Shalom,which in Hebrew means peace, wholeness and perfection

André Neher, a Jewish thinker living in Jerusalem, deeply aware of the existing conflicts, sees Israel’s election as one geared towards responsibility- a transforming responsibility. Its purpose is to accept whatever comes along in its train.2 For Neher, taking on the challenges of this responsibility, leads to fulfilling the promise of being a kingdom of priests (mamlekheth kohanim). For Neher, such a task can be realized only by reconciling three primordial facts:

a) First reconciliation (in Jerusalem): To promote encounter and overcome conflicts among Jews, Christians and Muslims, and all humankind across multiple divisions.

b) Second reconciliation (sacred and profane): To foster a state where atheism and religious co-exist.

c) Third reconciliation (within the Jewish people): To promote harmony between “patient” and “impatient” messianic hopes. Some see in the state of Israel a messianic sign, others, not yet. As Neher says, both are branches of the one and the same Jewish people.3

Rabbi Yehiel Grenimann, member of Rabbis for Human Rights, works with us, Comboni sisters, in supporting the rights of the Bedouin communities in the Judean desert. Considering the approach of ethic responsibility, which emerges from interfaith attitudes, and regarding the mission entrusted to the Jewish people in the perspective of “the chosen people”, he said, “Our return to Zion is a major event within the mysterious history that began with a lonely man-Abraham-whose destiny it was to be a blessing to all nations, and our irreducible commitment is to assert that promise, and that destiny, to be a blessing to all nations…”4

Israel, the Church, the Ummah Muslimah: A common commitment for the Universal Shalom

The Jewish election, seen as a sense of responsibility towards humanity, encourages us to reflect on the ethical dimension of life, perceived as common ground among religions. At interfaith level, it is important to recognize the spiritual bond that binds the Church and the Ummah Muslimah to the lineage of Abraham. It can be considered the “vocational unity” in which Israel is the “chosen people”, and in which the election has been materialized in the covenant at Sinai. Taking for granted that from a Christian perspective, the root remains valid and holy (cf. Rom 11:16), the Church’s identity appears deeply grounded in the Holy root of Israel. Enlarging the view, we consider the “Allegory of the Two Covenants” (Gal 4:0), in which Abraham is also the father of the Islâmic descendants. In the line of St Paul’s letter, Lawrence Feingold views Hagar and Ishmael as symbols of the first covenant, while Sarah and Isaac signify the second. The blessings are inclusive, the author reports the words to Hagar where it is said, “Rejoice, O barren one who does not bear; break forth and shout, you who are not in travail; for the children of the desolate are many more than the children of the married one” (Isaiah 54:1). The Mosaic Covenant given at Mt. Sinai, also includes Hagar.5

Therefore, the commandment to “love your neighbour as yourself” (Lev 19:18), plays a central role in the ethical perspectives of monotheistic religions. Jesus’ commandment to love (Jn 13:34–35), referring to the question, “Who is my neighbour? pre-supposes the existence of those who are not neighbours. The Commandments (two or ten), implies the concept of responsibility for the life of all those who are created “in the image of God”. This is what leads to the ethical commitment for Shalom, which in Hebrew means peace, wholeness and perfection. In the “open concept” of the term shalom, Israel, Church, and Islâm are asked to overcome ethnocentric, and antagonistic feelings, and search for a ‘circumcised heart’ which brings shalom in their actions and deeds.6

“Common Words between Us and You”: An Interfaith Ethos and the Wasatia (Moderation) Virtue Source for Justice and Peace

Considering the role of the Ummah Islamiyah within the mission for a just and peaceful society, Islamic theologians see the duty of the ummah referred to not only as a spiritual commitment, but as having a social dimension to bear witness to Truth and Justice, and answering God’s call. Modern conflicts and the challenges of modernity are reasons for the ummah and for religious communities to express an authentic religious belief free from extremisms.7

Standing in the Muslim ethical perspective, Mohammed S. Dajani Daoudi8, living in the “conflictive reality” of Jerusalem and longing for peace, states that Islâm, Judaism, and Christianity, like all religions, are called to implement moderation (wasatia), to overcome injustice.

With this awareness, Dajani reports religious writings about wasatia, saying:

Christianity teaches, “Moderation is the silken string running through the pearl chain of all virtues” (2 Pt 1:5-6).

Judaism teaches, “The Torah may be likened to two paths, one of fire, the other of snow. “Three things are good in small quantities and bad in large: yeast, salt, and hesitation” (Talmud: Berakoth, 34a).

Islam teaches, “They should rather pardon and overlook. Would you not love God to forgive you? God is Ever-Forgiving, Most Merciful” (Q. 24:22).9

Islamic theologians see the duty of the ummah referred to not only as a spiritual commitment, but as having a social dimension to bear witness to Truth and Justice

The Scripture perspective of Dajani enlightens also the “Abrahamic moral guidance”, common to Muslims, Jews and Christians. He refers to the first commandment to love in totality the only One God and “the Golden Rule” to “love your neighbour as yourself”. For Dajani, the core values of the “Abrahamic ethics”, such as liberty, equality, fraternity and justice are fundamental religious values that carry significant social and political implications. In the process of Muslim-Christian interfaith dialogue, in the document, “A Common Word Between Us and You”10, recalling the Qur’ānic verse, “…Come now to a word common between us and you, that we serve none but God” (Q. 3:64), the “common word” is love in the Jewish commandment of love for God and neighbour.

As an interfaith document, a common declaration is stated:

As Catholic and Muslim believers, we are aware of the summons and imperative to bear witness to the transcendent dimension of life, through a spirituality nourished by prayer, in a world that is becoming more and more secularised and materialistic. We affirm that no religion and its followers should be excluded from society. Each should be able to make their indispensable contribution to the good of society, especially in service to those most needy11.

As Comboni missionary sisters in the Holy Land, we experience the spirituality of reconciliation as being bridges among people, cultures and religions

In this common ethos, based on love and responsibility for the life of the marginalized, as Comboni missionary sisters in the Holy Land, we experience the spirituality of reconciliation as being bridges among people, cultures and religions; longing for harmony, wasatia and shalom. This binds us with the communities of Israel, the Church, and the Ummah Muslimah, in the mission entrusted to all of us by God. Interfaith human and spiritual unity are our attempts to mirror God’s Unity in Diversity. This is the wish from Jerusalem to the all interfaith and intercultural social communities.