MISSION: DIALOGUE FOR PEACE

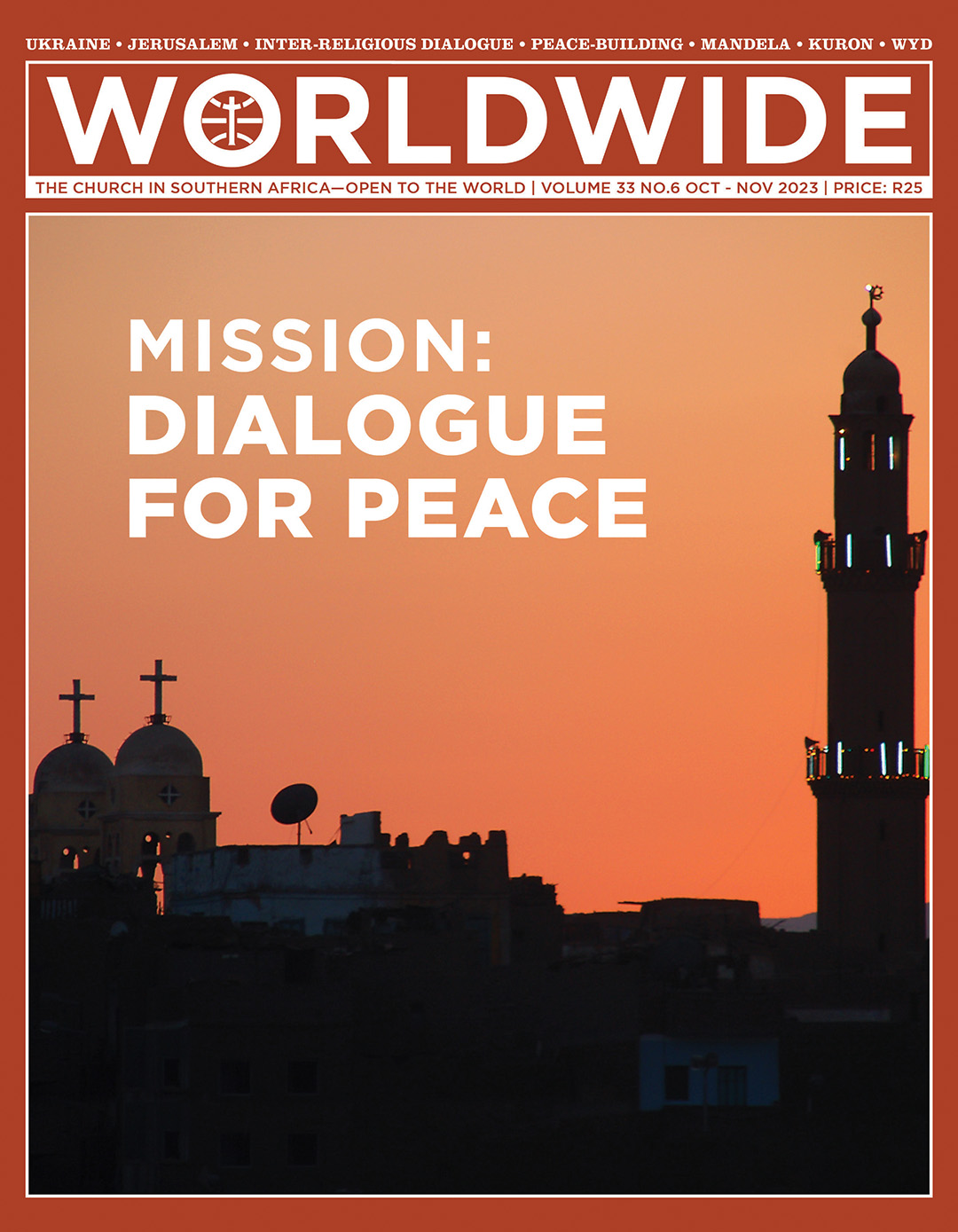

The Mosque minarets and church domes of the front cover, facing each other at twilight, transmit a sense of harmony and serenity. The two main religions of the world, Christian and Islam, are called to a mutual understanding and peace-building for the well-being of humanity. The essence of its traditions, far from fundamentalist interpretations, should lead their faithful to pursue together the values of justice and fraternity.

REFLECTIONS • DIALOGUE FOR PEACE BUILDING

United in the Spirituality of Peace, Love and Justice

Interfaith dialogue has become essential in building up peace and justice in the world. The richness of the different religious traditions must be shared to promote the values of the Kingdom of God for the benefit of all.

BY FABIAN ASHWIN OLIVER | THEOLOGY STUDENT, JOHANNESBURG

ONE OF my favourite childhood memories was that of visiting one of my mother’s closest friends, aunty Rabia. Aunty Rabia was a Muslim woman who stayed with her husband and two daughters. Despite my upbringing as a Catholic Christian, visits to aunty Rabia were filled with beautiful religious exchange. After Ramadan, we would be invited to celebrate Eid Mubarak together, characterised by joyful thanksgiving, tasty treats (Kanafeh and Mithai were my favourites), and thoughtful conversations in which our families shared their joys, hopes, and aspirations. In turn, aunty Rabia and family were involved and celebrated many Christian feasts with us. Years later, as I reflect on the current debates on interaction with other religions, I often wonder if my visits to aunty Rabia served as an important exemplar of what interfaith dialogue may look like from everyday lived experience.

In a recent conversation with a friend, we both reflected that unlike other international contexts where members of different faiths live in tremendous conflict, in South Africa tensions based on faith were not as common. This is because during apartheid people had one common enemy—that of racism and inequality. Thus, generally speaking, members of different religions all joined in the struggle against oppression. Today, the vision of interfaith dialogue is less defined and subject to much critical theological and social debates. This reflection maintains that the mission of interfaith dialogue is to be centred on unity in justice, love, and peace.

Sustaining a new way

To approach any meaningful vision for interfaith, we must rid ourselves of any Christian superiority in which we seek to convert the “ungodly”, “un-Christian” peoples of other religions into our own doctrine. We ought to move away from the notion that Christianity is better, and the rest are to be vilified. It is this superiority complex which supported Western exploitation of the now Third World, by forcefully colonizing Africa, Latin America, Asia, and others. Thus, Christian absolutism has blackened its relationship between the Christian minority and non-Christian majority (Hick and Knitter 2005:17-18). For Christians, it is important to remember that it is not those who say “Lord, Lord!” that will enter the Kingdom, but all those who do the will of God (Mat 7: 12-23).

While there are obvious irreconcilable differences in several faith traditions, we need to sustain a new language, humility, and humanity for dealing with our Christian presence in the world of diverse religions. An approach that acknowledges the sacred of our own whilst respecting the sacred in the other knowing that God is working in all our lives and, above all, God remains a mystery to be experienced and not a problem to be solved. We must celebrate difference and avoid conflict and debates of “the Bible says” or “there is only one way to salvation, and we have it.” Former Anglican archbishop Desmond Tutu poignantly reminded us that “God is not a Christian. All of God’s children and their different faiths help us to realize the immensity of God” (2011).

The mission of interfaith dialogue is to be centred on unity in justice, love, and peace

Fr Richard Rohr says that any healthy world religion “shows you what to do with your pain, with the absurd, the tragic, the nonsensical, the unjust and the undeserved—all of which eventually come into every lifetime” (2018). He adds that if we avoid dealing with pain, we will transmit it onto others. For example, Buddhism 2017:157) and Christianity agree that suffering is part of our ego-identity and embodied existence. More importantly, both are committed to take the person out of suffering and into nirvana or eternal life. Without sounding judgmental, people who often behave as “gremlins” (for lack of a better word) have often not made time to notice or embrace the wounds in themselves, to weep if they should, and to transform from it and be united in the wounds and healing of others. Hurt people, hurt people, as the saying goes. It is disturbing how in certain corporate and educational spaces, compassion and love is seen as an obstacle to the goal of profit and excellence. Increasingly, we are living in a world still thriving with profit and invention, but lacking in humanity; with people feeling more exploited, unseen, overwhelmed, anxious, separated from their families, and poor. Any good religion must tap into these realities, ushering in hope, love, compassion, and life beyond the everyday tragedy many find themselves in.

Interfaith towards the common good

The Vatican II document, Nostra Aetate (NA) made it clear that “the Catholic Church does not reject anything that is true and holy in other religions” (NA 2) and invited the faithful to nurture dialogue with our sister/brother religions (Freeman 2017:157). Liberation theologians Leonardo Boff and Fr Jon Sobrino agree that we cannot know Jesus unless we follow him and put his words into practice (and our experiences differ from person to person). Hence, we cannot know exclusively that Jesus is God’s final revelation to humanity based on doctrine or personal experience alone, but also in the uniqueness of Jesus which is found “in its embodiment;” meaning that unless we practise Christian dialogue with other religions, following and applying the message of Christ in dialogue and prayer with other faiths, we cannot claim what the uniqueness of Christ means (Hick and Knitter 2005:191-192).

Any good religion must usher in hope, love, compassion, and life beyond the everyday tragedy many find themselves in

It is out of this spirit that Pope Francis and Imam Ahmad Al-Tayyeb met in Abu Dhabi and produced the document on Human Fraternity: for world peace and living together (2019). The document emphasizes that globally there are still high levels of poverty whilst the rich minority get richer. There exists increased levels of terrorism, extremism, discrimination, and overwhelming ecological degradation. It acknowledges how systemic patriarchy still marginalizes women today. Despite this, the document calls for religious commitment to peace and solidarity expressed in respective religions. Here, dialogue is “transmitting the highest moral virtues that religions aim for. It is also means avoiding unproductive discussions” (2019).

‘To pray and work for justice.’

When the Christian, Buddhist, Jew, and members of other faiths get together, what shall they pray about? While we may have different creeds and methods of prayer, every person is called to bear witness—to be missionaries—to the best of their faith traditions. This is to pursue justice in a world still muddled in human indifference. To pray and work for justice means to be united in a spirituality that promotes life, combats injustice, and stands with oppressed and vulnerable offering a vision of the world in which all can experience and celebrate God’s creation, beauty, extend human intimacy, and witnesses miraculous possibility. Religious dialogue is called to journey with those who experience loneliness, unemployment, those who are recovering from difficult childhoods, figuring it out of what it means to be a man, women or person, for those working through difficult relationships, and those waiting on healing. It is here, we can find common expression of being diverse in faith traditions but united in the spirituality of justice, love, and peace.