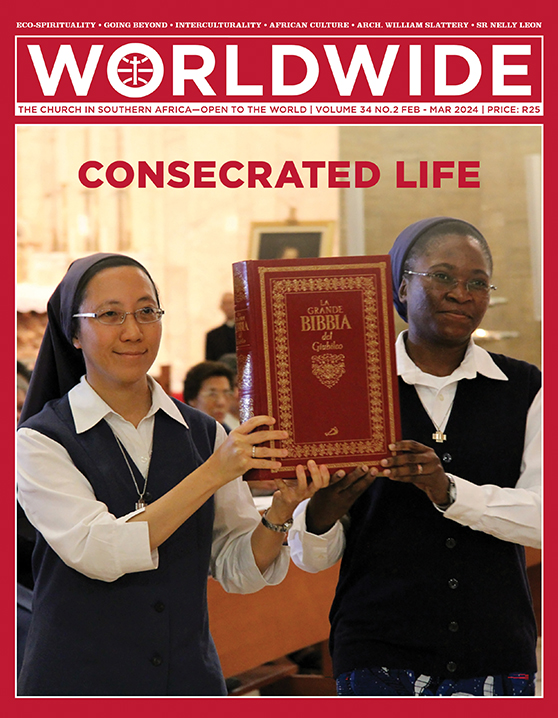

CONSECRATED LIFE

The painting on the front cover entitled “The disciples of Emmaus” reflects our journey of hope. Jesus not only walks with us, but gives us the wisdom to perform our ministries and opens our eyes to see Him in the people that we are serving.

INSIGHTS • DIRECTIONS

EXAMPLES OF SERVICE

BY Mike Pothier | Programme Manager, SACBC Parliamentary LIAISON OFFICE, CAPE TOWN

MORE THAN 60 years ago a small book with what would now be considered an unacceptable title was published in America: Bishop for the Hottentots. It is a memoir by John Marie Simon, an Oblate of Saint Francis de Sales (OSFS), who was the first bishop of what is now known as the Diocese of Keimoes-Upington, in the Northern Cape, and it details his experiences as a missionary in that area between 1882 and 1909, including the construction of the famous cathedral at Pella, just south of the Orange River.

If it were written today, the people it refers to would be more appropriately called the ‘Khoekhoe’. Another word in the title that should also be noted is the word ‘for’, as in bishop ‘for’, and not ‘of’, the indigenous people of that district. This reflects how Simon saw himself: to be something ‘for’ someone implies a spirit of service, and indeed, Bishop Simon and his OSFS companions were known for exactly that.

All religious congregations are called to serve in one way or another, and there is much that the contemporary world can learn from the way in which they serve. To some extent, indeed, they present an opposite polar to the dominant norms in many areas of secular life, especially in politics—the urge to dominate, to win, to grab power and to ensure self-advancement. (We should not be naïve, of course; there are many examples of Religious who have lost sight of the need to serve and have instead become as besotted with power, status and position as any politician!)

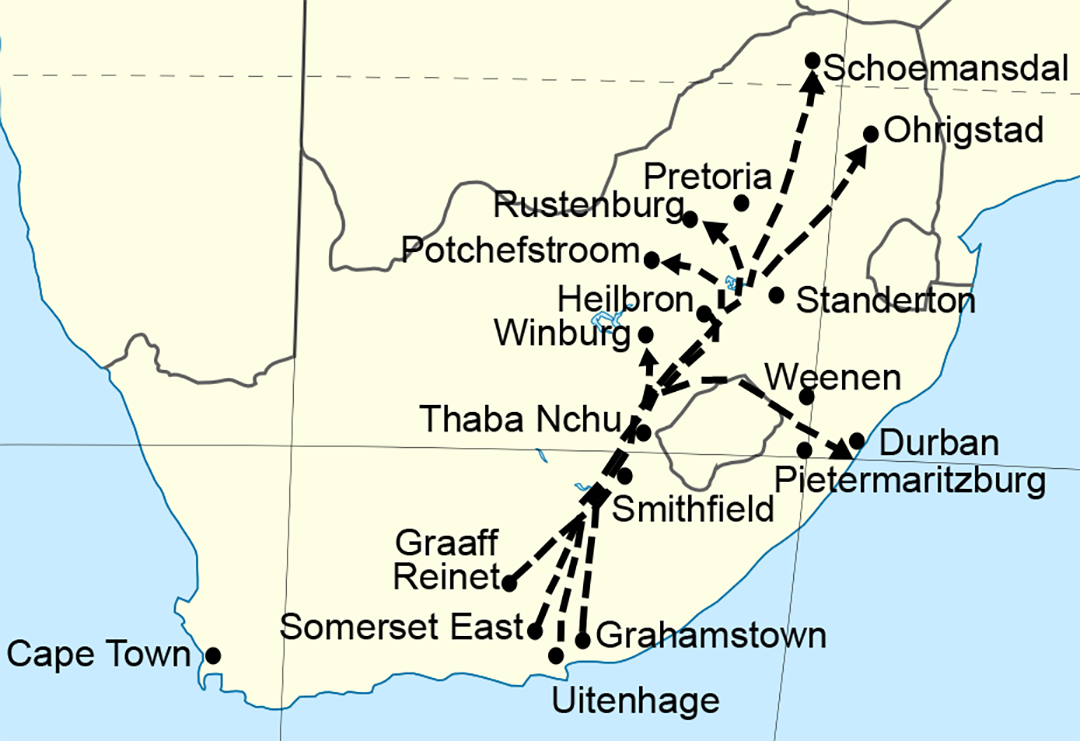

One of the great strengths of religious congregations, as of the Catholic Church as a whole, is their international character. Especially in a missionary territory like South Africa, this meant that priests, nuns, and brothers from a variety of countries came here to spread the Gospel and to help build a local Church. Bishop Simon was French, and in the early period of missionary work, French Religious worked in various parts of the country, especially in the interior, in the former Natal Colony, and among the Basotho people.

In those day almost all the traditionally Catholic countries of Europe were represented in South Africa—there were German, Belgian, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese missionaries, followed by English, Dutch, and Polish ones. In sheer numbers, though, the Irish were probably the most numerous. More recently, the mantle has passed to missionaries from the east—from India, Sri Lanka and the Philippines, among others—and indeed also from other regions in Africa.

Many of the ‘foreign’ Religious who came to Soth Africa had a very different attitude to matters of racial and social justice, compared to that of the local white population. Obviously, there were those who did not want to ‘rock the boat’, and simply accepted South Africa’s racial laws, but a significant proportion of them did not; and in their ministry they opposed Apartheid and worked towards empowering its victims.

It is probably fair to say that the Irish were at the forefront in this regard. They brought with them the memory of their own nation and the Church’s oppression during the centuries of British colonialism in Ireland, and they could hear the echoes of that history in the discriminatory social and legal structures they found in operation here. It is no coincidence then that it was the Irish Cabra Dominican Sisters who first openly defied the Apartheid education system by opening their schools to children of all races. They were soon followed by other orders —the Marist and Christian Brothers for example— and a significant crack was made on the edifice of segregated education.

Yes, there are also many examples of foreign Religious who patronized the local people, looking down on their cultures and regarding them as inferior, lacking any sensitivity to local customs and ways of life. These people practiced a form of ‘imperial Christianity’, rather than one of service, but they were—one hopes—a minority.

Various congregations have recorded the histories of their work in South Africa, but it is a pity that no one has yet produced an overview of the contribution of Religious to social and racial justice, and indeed to liberation, in our country. Heaven knows, we need all the examples of true Christian service we can get!