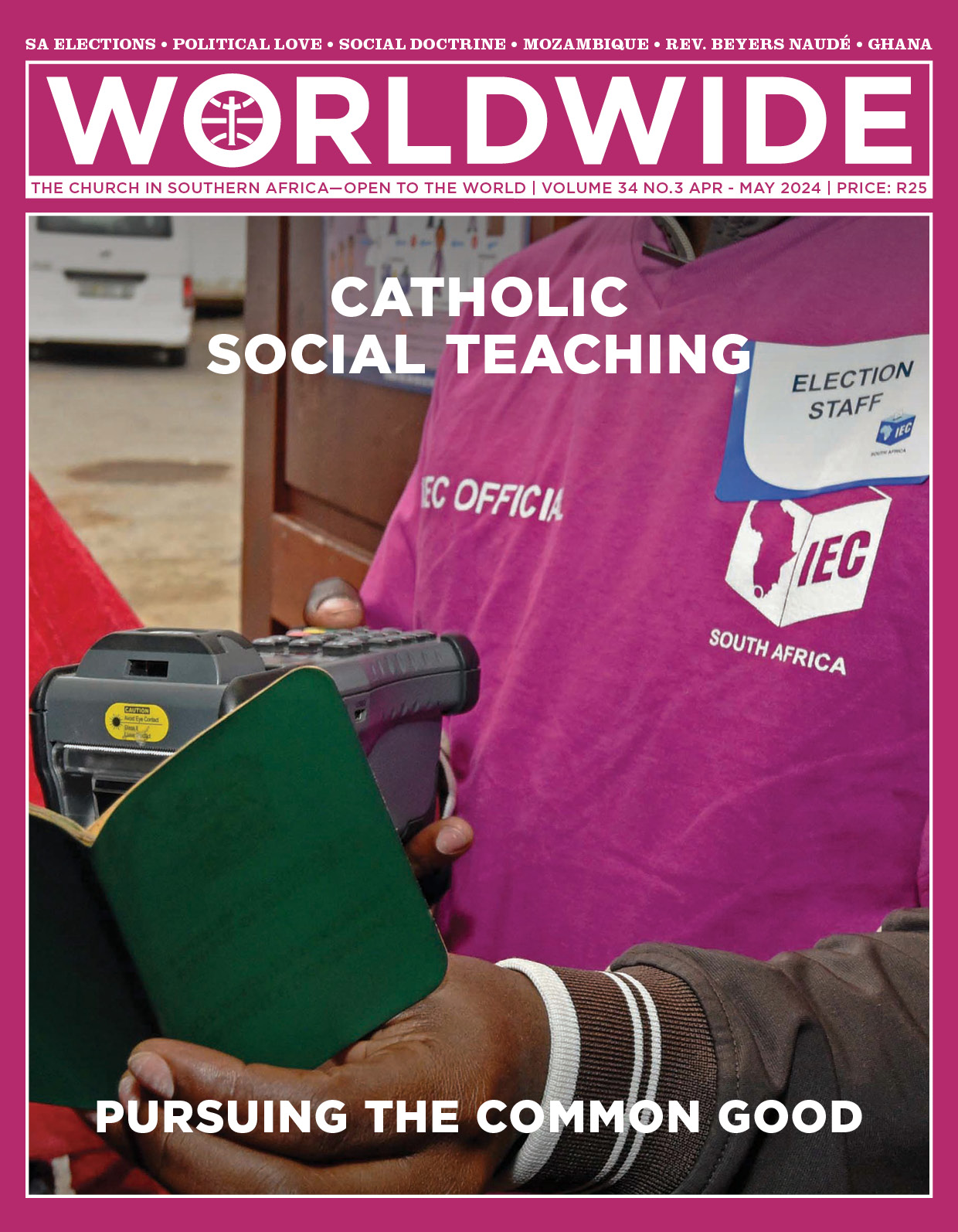

CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING, PURSUING THE COMMON GOOD

It is the honourable responsibility of Christians to contribute by means of active participation to building a society where the common good is fundamental. As Pope Benedict XVI affirmed: “There is a need for authentically Christian politicians but, even more so, for lay faithful who witness to Christ and the Gospel in the civil and political community.” (Address to the 24th Plenary Session of the Pontifical Council for the Laity).

YOUTH VOICES • SAFEGUARDING THE ENVIRONMENT

DIALOGUE TO BETTER UNDERSTANDING

Care for the environment is an issue of concern in today’s world. The author poses the question of how we can incorporate principles which the Catholic Social Doctrine of the Church offers to progress towards a better preservation of our common home.

BY JILL WILLIAMS | CANDIDATE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, PRETORIA

THE CATHOLIC Social Doctrine of the Church is something that most young people like me are not aware of or have merely vaguely heard of in one or another sermon. In efforts to broaden my understanding of the subject, I did what every young person does. I consulted the internet. The various sources available seem to bring the same point home: The Catholic Social Doctrine of the Church seeks to offer an understanding of the person in relation to themselves and God, who they are as a person, and the way they are connected to the people around them and the society and world in which they live. Oddly enough, most teenagers (and adults) typically grapple with these issues, sometimes even to the point of deep depression or worse. Isn’t it amazing how we all tend to look for answers about ourselves and about God outside of the Church? We tend to listen to the news and social media with a keener ear than to the teachings of the Church, as if God had decided that the Church, which He founded, was no longer where He wished to give fresh revelation of Himself.

Taking care of the environment

In this article, I would like to focus more on the Doctrinal pillar, “Safeguarding the Environment”, with brief reference to the pillar “The Freedom of the Human Person”. I found each to be quite eye-opening as they speak to something deeper than a do’s and don’ts list of how to treat yourself or one another, but instead refer to Scripture to see how we can practically mirror Jesus’s way of relating to the environment, people, and Himself as fully man and fully God.

Safeguarding the Environment implies continuous dialogue. It is found in the relationship of man with God and in his relationship with the world:

“[This] is a constitutive part of his human identity… The Lord has made the human person to be a partner with Him in dialogue. Only in dialogue with God does the human being find his truth, from which he draws inspiration and norms to make plans for the future of the world, which is the garden that God has given him to keep and till (cf. Gen 2: 15). Not even sin could remove this duty, although it weighed down this exalted work with pain and suffering (cf. Gen 3:17-19).” (Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace 2024, 452).

The first thing to consider from this text is that the role given to humanity to care for the environment is one that cannot be undone by anyone, no matter how much we reject God or turn away from Him. Ignoring God will no doubt make the work more tedious, but it certainly will not nullify it. As much as we may reject, reduce, debate, or dissect the meaning of ‘subduing’ and having ‘dominion’ over the earth (Genesis 1:26-28), we still need to perform this duty. And clearly, the signs of not taking this duty seriously, has had massive and deadly implications for both humans and the fauna and flora we were entrusted with.

Unity with nature

The second consideration stems from the question I came across earlier in my studies. Are human beings separate from the environment? We certainly act this way, despite being mortal creatures. Why then do we see ourselves as something separate from the natural world? We certainly are part of nature. Peck (2023) suggests that the belief that we are separate from the natural world has led to our lack of care for it. This makes the role of “keeping the earth” far more important, since destroying one’s natural home equates to destroying oneself. In previous articles, I have referred to indigenous peoples such as the San, who believe that we are custodians and not owners of the earth. I believe that the Doctrinal Pillar of Safeguarding the Environment is in agreement with this, as God is the ultimate source or beginning of everything; any form of right over any created being was given to us by His grace and mercy and can be taken away from us by God alone, as is seen in the parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14–30). Based on the first point above, it is clear that God does not intend to take the role of custodianship away from us, but prefers us to do this the way He originally intended, as discussed below.

One of the major factors impacting the destruction of the environment is development and urbanisation, leading to pollution, burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, etc (National Geographic 2024). Although these are economically driven and beneficial activities which may or may not have positive social outcomes, there are often little to no participatory discussions or dialogues with local stakeholders on how these activities should take place. Are those who will be impacted by such activities given the opportunity for an open and meaningful discussion with developers? Do their voices matter?

Listening to God’s voice

Furthermore, is the floor opened to discerning the voice of God and His plan and intention for those projects? The last question might be the most contentious as various religious groups might be involved. The following query might be raised: which god are we consulting? However, the fact remains clear; God is hardly consulted when making future plans for the care of the world. From my experience in the construction and development industry, we rely heavily on legislation and Development Plans which stem from the National, the Provincial and or the Local/ Municipal level, to inform framework designs of, for example, proposed business precincts. Those documents are in a sense seen to be “sacred”, as one must ensure that the vision for the area aligns with that of the larger context and the plans for that city and province. The plans are never without mission and vision statements that align with those of the national vision and mission statements. While there is nothing wrong with this, how often do we check whether these plans align with the vision and mission statements of the Church? I suppose many would see this as an unnecessary exercise. It would, however, be interesting to see how one could overcome or mitigate various challenges in implementing developmental strategies at ground level.

If this sounds far-fetched, then be reminded of the story of Joseph in Egypt in Genesis 41, and how economic future planning for a time of natural disaster was possible through divine intervention and ingenuity. Pharaoh was given an encrypted dream by God (even though he probably never knew God). Divine revelation exposed that there would be several years of abundance in Egypt, followed by several years of severe famine that would affect the surrounding nations as well. The revelation and interpretation of the dream was given to Pharaoh by Joseph, who was in a relationship with God. If neither took note of the dream and its meaning, they would not have arrived at the realisation that a major, life-threatening event was approaching their nation. From this revelation, a creative solution, also provided by God, was given to Joseph, who was in dialogue with Him. This ensured that the storehouses were enlarged and that more grain was stored than in previous years, to provide for their nation during the impending years of famine.

In the various dialogues above, there is a sense of freedom regarding how and when the various role-players responded to the revelation received from God, as the value and limits of freedom under the Doctrinal Pillar of “The Freedom of the Human Person” indicate:

… “For God has willed that man remain ‘under the control of his own decisions’ (Sir 15:14), so that he can seek his Creator spontaneously, and come freely to utter and blissful perfection through loyalty to Him. Hence man’s dignity demands that he acts according to a knowing and free choice that is personally motivated and prompted from within, neither under blind internal impulse nor by mere external pressure.” (Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, 135).

Each role-player in the story of Joseph was free to either listen to or ignore God and the other role-players. Whatever they decided to do would have an impact on others, and on the way they were able to cope with environmental pressures. Being custodians of the earth means admitting that we need guidance in how and when we do things, in a spirit of freedom. If a greater amount of listening and meaningful communication occurred in the dialogue between decision-makers and various role-players, the needs of people, fauna, flora, and the homes in which each reside would be more effectively designed and planned for. This could cause a great shift in the way we live and operate in the world today. If we will always be the keepers of this earth, why don’t we make the most of it?