CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING, PURSUING THE COMMON GOOD

It is the honourable responsibility of Christians to contribute by means of active participation to building a society where the common good is fundamental. As Pope Benedict XVI affirmed: “There is a need for authentically Christian politicians but, even more so, for lay faithful who witness to Christ and the Gospel in the civil and political community.” (Address to the 24th Plenary Session of the Pontifical Council for the Laity).

PROFILE • REVEREND BEYERS NAUDÉ

EMBRACING THE TRUTH REGARDLESS THE COST

The life of Reverend Beyers Naudé is inspirational, especially on account of his receptiveness to embrace the values which Catholic Social Teaching upholds, such as respect for human dignity, solidarity and common good, deviating from a context in which these values were trampled on.

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

THEY SAY that Catholic Social Teaching (CST) is the Church’s best kept secret. Certainly, many Catholics feel on shaky ground when it comes to identifying what should be ingrained in our DNA. And sometimes we must admit that there are members of other denominations, other faiths, who lead their lives in such a way that we couldn’t slide a sheet of paper between them and CST.

Imbedded in the values of CST

One South African who cannot be separated from the concepts of Catholic Social Teaching is the Reverend Beyers Naudé, who in later life found God in all he met, and especially in the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed. Naudé began his career as a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church, but later embraced what we recognise as the Catholic call for human dignity, a pillar of CST. He paid the price when he was ostracised by many in the white community because of his denunciation of apartheid.

Naudé began his career as a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church, but later embraced what we recognise as the Catholic call for human dignity

“Solidarity” is another pillar of CST that comes to mind when we consider the life of Beyers Naudé: a solidarity that motivated him to stand side by side with Black sisters and brothers during that most difficult of times in South Africa, regardless of the personal cost.

Indeed, what about “the common good”? Catholics are taught that the common good means that the fruits of the earth belong to everyone. At a time when the Black majority in South Africa was denied so much as the pips of those fruits, Rev. Naudé sought to ensure a better future in which “the option for the poor” was addressed, and “peace” would be possible for all.

For taking this stance, he was denounced as a traitor.

We could go on, delving into the areas of Catholic Social Teaching that this man adopted, albeit quite possibly unconsciously. He sought not only basic human dignity, but “the dignity of work and participation” during those years when white supremacists saw fit to deny the majority of South Africa’s population these rights.

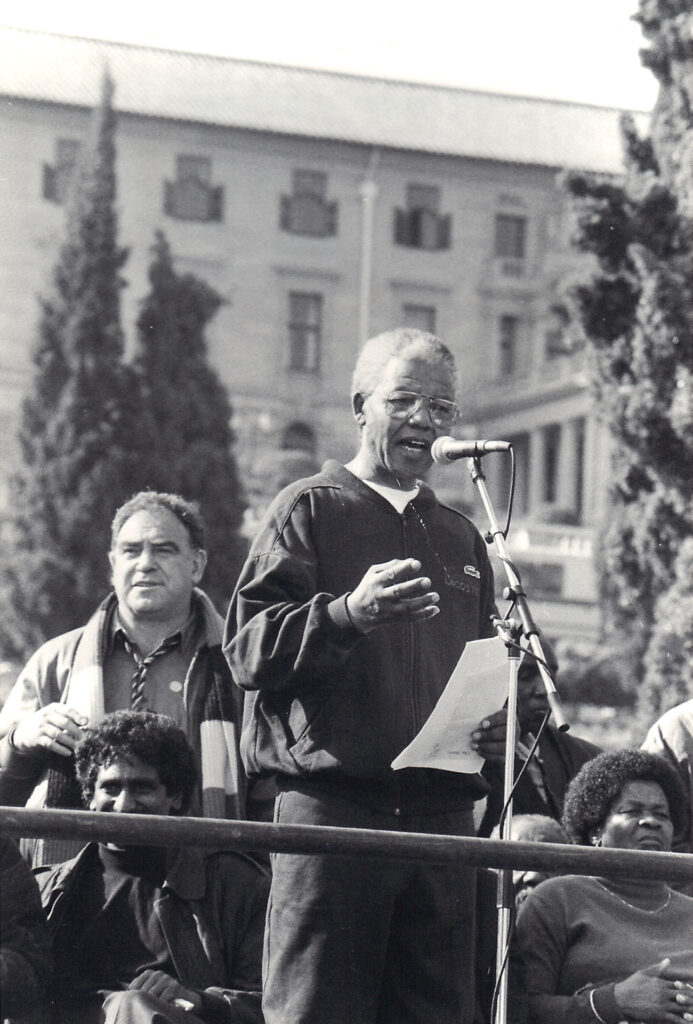

This bravery in speaking out for such a framework of life earned Naudé this accolade from Nelson Mandela: on Naudé’s 80th birthday, the then South African President described him as a “shining beacon”, saying “It demonstrates what it means to rise above race, to be a true South African.”

Origins

Let us go back to the beginning of Beyers Naudé’s life to explore how a man raised in the Dutch Reformed Church—a church that worked hard to justify the values of apartheid —came to hold as sacred what true Catholics should hold at the heart of their faith.

One of eight siblings, he was born on May 10, 1915, in Roodepoort, in what was then the Transvaal. His father was something of a firebrand in the Dutch Reformed Church. Reverend Jozua François Naudé was responsible for some of the first biblical translations into Afrikaans and helped embed it as an official South African language. He was also the first chairman of the Broederbond, a secret society of Afrikaner leaders that liaised with government during apartheid.

Beyers Naudé even joined the Broederbond, becoming its youngest member at age 25

All the influences as he was growing up confirmed Beyers Naudé in his father’s way of thinking. He gained a Master of Arts (MA) at Stellenbosch University, known for nurturing Afrikaner intellectualism; then studied theology there. Fellow students included Hendrik Verwoerd and John Vorster, who both served as apartheid prime ministers. Beyers Naudé even joined the Broederbond, becoming its youngest member at age 25, and seemed entrenched in their world when in 1940 he was appointed assistant minister at the Dutch Reformed Church in Wellington, a small town near Cape Town. His preaching at that time was undoubtedly founded in the racial segregationist philosophy of the then government.

U-turn moment

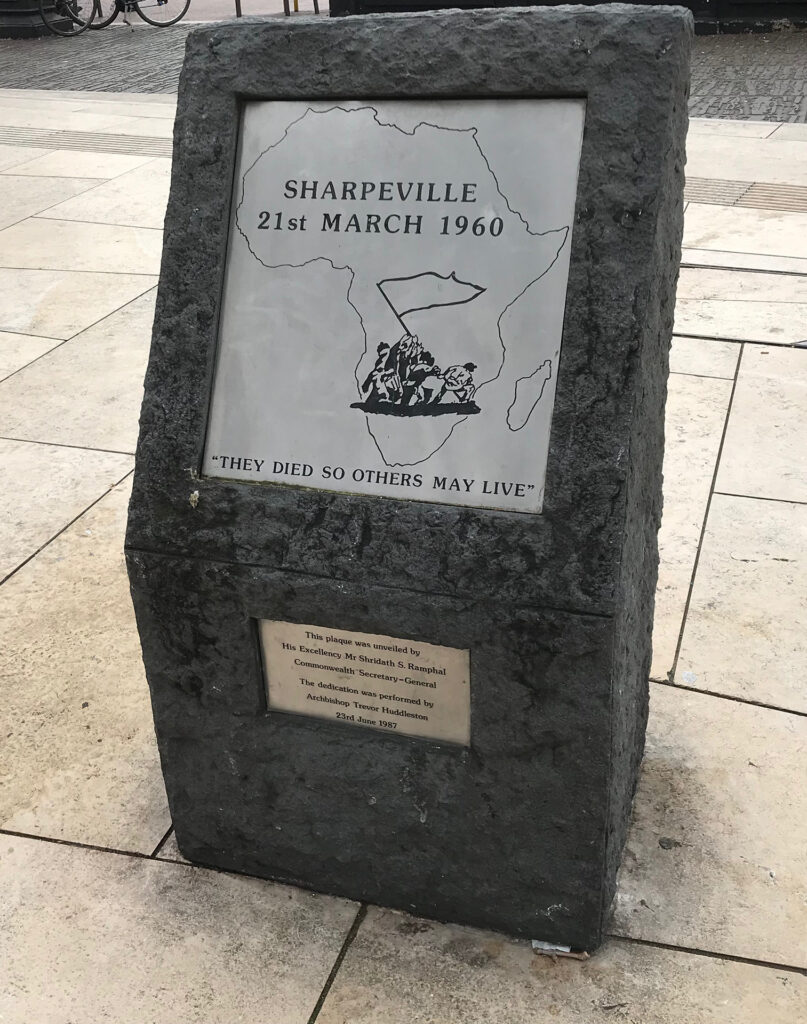

With men like Naudé, however, there is always that Damascene moment that changes life forever. For him, the Sharpeville massacre was that deciding moment.

It was not the first time that he had begun to question apartheid. There had been chinks of light stabbing at his beliefs. In Potchefstroom, for example, he had discussed aspects of apartheid policies with fellow ministers and, indeed, Broederbonders which were questioning the validity of these racist practices. But it was when government troops massacred 69 protesters in 1960 that his mindset altered completely and brought him so close to Catholic Social Teaching.

It wasn’t easy, of course, to change track. He had been preaching in the Dutch Reformed Church for two decades and had been steeped in its beliefs from childhood. The year after the Sharpeville massacre, he was appointed moderator of the Southern Transvaal Dutch Reformed Church, but at the same time helped to found the Christian Institute, an ecumenical organisation that challenged the established church on the issue of apartheid.

His life, his preaching, his very soul was becoming increasingly conflicted. He was beginning to speak out against the core of the white minority’s racist strategies, calling out the immorality of the migrant labour system’s destruction of Black family life. He concluded that he could not continue within the church that had been omnipresent throughout his life.

In September 1963, he condemned apartheid from his pulpit in Aasvoëlkop. This was a step too far for the Afrikaner community and he was in turn condemned as a traitor.

Leaving ministry at the Dutch Reformed Church

This was the beginning of a new life for Beyers Naudé, and symbolically he took off his robes and left his church. The Afrikaner community just as symbolically casted him off. He could only tell his wife, Ilse: “Whatever happens, we will be together, and God will be with us.”

Although he continued to preach in Black Dutch Reformed congregations, this became untenable, and he was forced to resign as a minister in 1965. He was now pursued by the Security Police, who raided the Christian Institute’s offices in May of that year.

The nonviolent approach of his campaign against apartheid was met with mixed feelings in South Africa while it was lauded in Europe. In 1972 he delivered a sermon in London’s Westminster Abbey, and held talks in West Germany with church leaders. Amsterdam’s Free University awarded him an honorary doctorate in Theology in October 1972 for “exceptional merit for the development of theological science”.

Back in South Africa the following year, the Christian Institute was investigated by the Parliament’s Schlebusch commission, established in 1972 by then Prime Minister BJ Vorster specifically to investigate four anti-apartheid civil society organizations, including the Christian Institute. The fact that Vorster had studied alongside Naudé perhaps spurred the prime minister to persecute this man who had so radically changed his thinking and was prepared to say so publicly.

1974 saw Naudé receive an honorary Doctor of Law from the University of Witwatersrand. He was also honoured with the Reinhold Niebuhr Award for “steadfast and self-sacrificing services in South Africa for justice and peace”. His passport, which had been confiscated, was returned so that he could travel and receive the award at a ceremony in Chicago, US. On his return it was once again confiscated.

Persecution and arrest

In December 1975 Naudé was refused a passport to travel to London to address the Royal Institute of International Affairs, and his speech was presented in his absence. On the recommendations of the Schlebusch Commission, four anti-apartheid organisations were denied foreign funding, and funds and documents were seized. In on-going prosecutions, Naudé was jailed in 1976 for refusing to testify and to pay a fine, although that fine was paid by a supporter, and he only spent one night in prison.

In 1977, Naudé and the Christian Institute were banned. He was placed under house arrest and was only allowed to speak to one person at a time. Even so, he managed to set up a ministry to council pastors and he continued one-on-one talks with other activists, including Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Awards

The world outside South Africa continued to hear of his activism and to award him prizes, such as one from the Swedish Free Church for reconciliation and development and the Bruno Kreisky Foundation award that recognised his “untiring work in race relations”.

When he finally broke completely from the Dutch Reformed Church in 1980, the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk in Afrika welcomed him. This was the year when his house arrest was lifted, but he still wasn’t allowed to leave the Johannesburg magisterial district.

Amid all this persecution, it seems amazing that in 1983 he was awarded an honorary Doctorate from the University of Cape Town. This was a year before his banning order was lifted completely and he was able to immerse himself entirely in his mission to end apartheid. In 1985 he became the secretary-general of the South African Council of Churches, stepping into the shoes of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Two years later, he would be a member of the Afrikaner group meeting with ANC representatives in Senegal.

During the seven years that he was banned, he chose his allies but did not take instruction from them. This led to the ANC criticising his support of other organisations, including Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement, which empowered and mobilised much of the urban black population. That element of “dignity of work and participation” that Naudé no doubt recognised and supported in Biko’s Movement reminds us again that while Naudé might have remained true to his Protestant background, his philosophy embraced all these elements of Catholic Social Teaching.

Spirit of reconciliation and peace

In 1990, despite the restraint he retained in his relationship with the ANC, he joined its leaders, including Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Joe Slovo, to meet for the first time with members of the apartheid government. He still, however, preferred to stay out of the headlines—until the day in 1994 when he heard F.W. de Klerk’s speech declaring a new South Africa. He publicly declared “What I had dreamt, hoped and worked for is becoming a reality.”

Societal change is slow, but it is interesting to learn that after 1994, Naudé was not only welcomed back to the Dutch Reformed Church, but on a personal level he and his family were no longer ostracised.

His work in the final decade of his life included speaking to conservative congregations around South Africa, nurturing in resistant pockets the spirit of reconciliation sought by Nelson Mandela. It was difficult work, but when he died in September 2004, he had come a very long way from the bitter prejudices that surrounded him in the first half of the 20th century.

Beyers Naudé again reminds us of Catholic Social Teaching, which has peace at its heart: peace is a cornerstone of the Catholic faith, and it clearly became the cornerstone of Beyers Naudé’s beliefs.