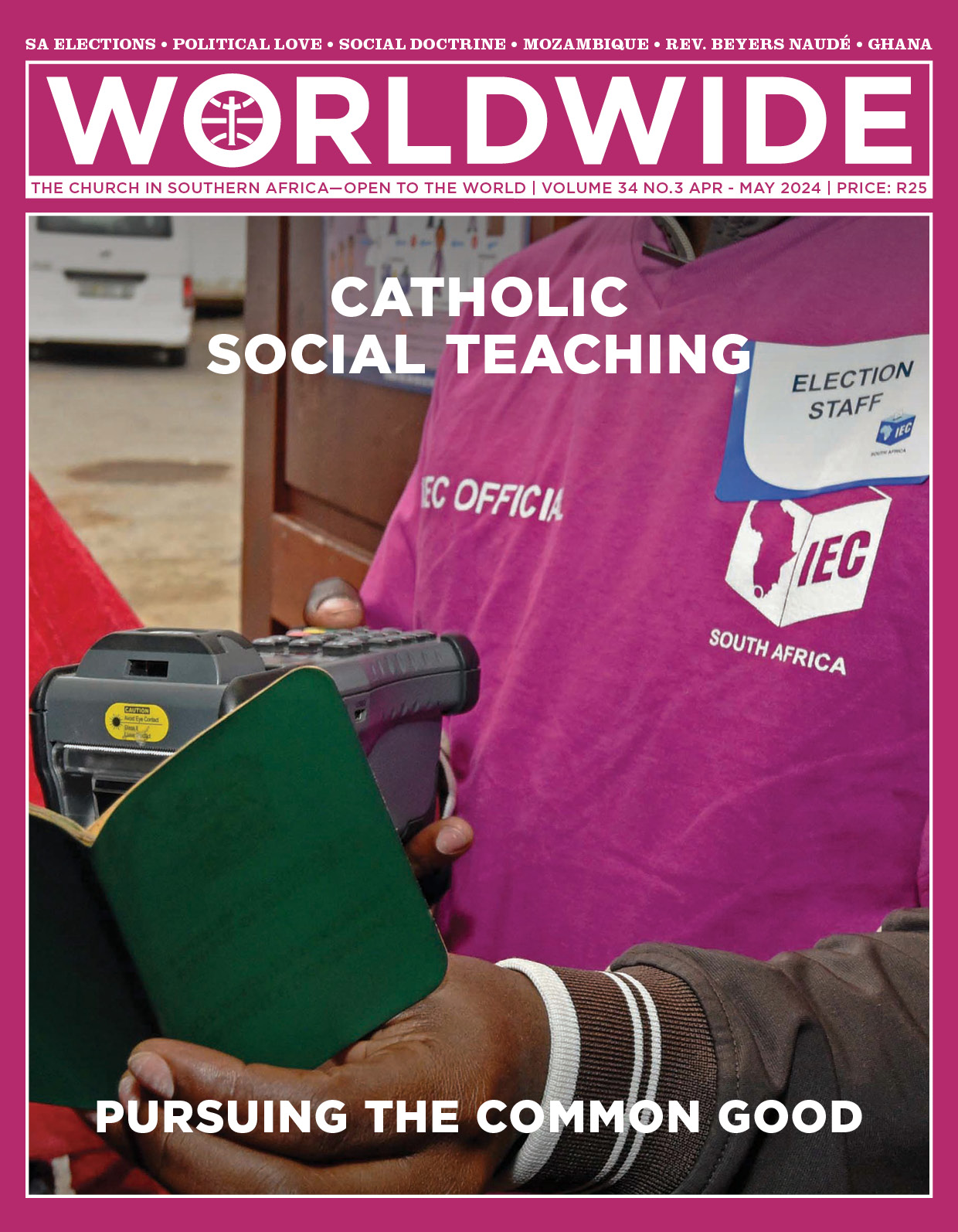

CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING, PURSUING THE COMMON GOOD

It is the honourable responsibility of Christians to contribute by means of active participation to building a society where the common good is fundamental. As Pope Benedict XVI affirmed: “There is a need for authentically Christian politicians but, even more so, for lay faithful who witness to Christ and the Gospel in the civil and political community.” (Address to the 24th Plenary Session of the Pontifical Council for the Laity).

WORLD REPORT • BUILDING COMMUNITY

THE KUKAH UNIVERSE

In 2008, Most Rev. Matthew Hassan Kukah, Bishop of Sokoto, Nigeria, started developing the idea of a centre for research, dialogue and action geared towards the development of the country. Now active in 25 Nigerian states, the Kukah Centre focuses on projects such as local politics, group-coexistence and humanitarian issues. Peace, cohesion, and democratic growth are the main features which mark the work of the centre.

BY CARLA FIBLA GARCÍA-SALA | JOURNALIST, FROM NIGERIA

Sani Umar Jappi, the sarkin yaki (‘king of war’ in Hausa) Gagi—a town located south of Sokoto— is also the head of its district. He is the leader of a multicultural community which is a benchmark in northern Nigeria. “This is a mini-Nigeria, with a high population density: Ibo, Ijaw, Hausa, Berom, Itsekiri, Yoruba and Gbayi are spoken here. It is home to believers of various religions. We solve common disputes, face challenges—also present in national politics—together and intervene in order to change men’s attitudes towards serious issues such as domestic violence”, sarkin yaki Gagi explains. In his modest palace, goats and chickens roam under the watchful eye of those who listen to him, apparently understanding the direct and surprisingly feminist discourse of their leader. “Education and health must be applied to local solutions, to invest in the future of our children. The community must bring about change and be proud of it,” he continues, raising his voice when one of his subjects gets distracted, or asking questions to those who do not seem to pay enough attention to his discourse. Helping young people to stay away from drugs, involving women in decisions inside and outside home and encouraging family planning so as to escape poverty and vulnerability, are palpable achievements in Gagi.

Sokoto: The epicentre

Sarkin yaki Gagi is one of the direct partners and beneficiaries of the Kukah Centre’s (KC) actions. The KC operates in Sokoto through the Bakhita Initiative which was born out of the Justice, Development and Peace/Caritas, founded in 2016 by Bishop Kukah to foster good governance and leadership for development. The KC operates in 25 of the 36 Nigerian states and it works together with community, religious and social leaders to implement its projects.

The Sokoto Caliphate—where Sharia (Islamic law) is widely applied and there is little recourse to conventional courts to resolve inter-ethnic disputes and conflicts—might seem hostile territory for the KC. However, the professionalism with which the KC employees carry out their field work— identifying difficulties and raising awareness of them among the population, inviting them to debates and reflections, and accompanying internally displaced people who lack food and basic resources— earns them respect and recognition.

The machinery that drives the KC is well oiled, allowing its members to react immediately to outbreaks of violence, resurgence of perennial inter-religious conflicts (between Muslims and Christians) or territorial conflicts (between herders and farmers). One of the KC’s greatest achievements is that it bases its work on respect and dialogue which leads to political will that transforms itself into development.

Kaduna: The origin

The road from Abuja to Kaduna was impassable until recently. Kidnappings in daylight and persistent insecurity in the north of the country meant that the chances of not reaching one’s destination were high. Now the dirt roads, coming off the main road, are guarded by camouflaged military posts, a permanent surveillance which allows daytime traffic. Only its huge potholes, caused by freight trucks, force people to slow down and pass from one side of the highway to the other, often ending up driving in the opposite direction.

The situation improved because now “there is dialogue” between the communities and “there is talk of peace and conflict resolution involving religious leaders, young people and women.”

“In 1987, the region experienced its first violent crisis when our priest, Fr Enneri, was killed. In 1992, clashes erupted between Muslims and Christians when a copy of the Koran was burnt. In 2000, Sharia law was introduced and two years later disputes resurged over ways of dressing. In 2011 a political crisis over the elections broke out and in 2013 Fulani herdsmen destroyed churches and farmers’ fields,” says Bamawi Oche, who is responsible for the maintenance of the building which has hosted the KC in Kaduna for decades. Alongside him, Victoria Madaki says that “this place was always attacked because it was believed to be a church, a place of worship. It was bombed and had to be rebuilt several times.” The workers we spoke to agree that the situation improved because now “there is dialogue” between the communities and “there is talk of peace and conflict resolution involving religious leaders, young people and women.” The KC adapts itself to the realities of each state in which it works. “Kidnappings are still the main problem; they can ask for up to 100 million naira [about 118 000 euros] for your own or your family’s release. It’s crazy. Those who are affected desperately attend any event to talk about their plight and to ask for support. Recently a man came asking for 40 million naira for his wife and three children. They threatened to kill them if that amount was not paid within three days. They put his five-year-old son on the phone while beating him. Kidnappings are still very active,” admits Madaki.

Working together

We visited Muslim and Protestant Christian leaders and officials with Methodius Karfe, a KC coordinator, and the Bishop of Kaduna. “We hold monthly meetings on issues of concern for the population. When crises arise, we activate our networks to de-escalate tensions. There are synergies between religious leaders and the country’s security forces”, says Karfe. He also stresses the need to resolve family conflicts, “providing knowledge to parents to keep their families together” in the face of adversity. He refers to the economic or livelihood problems faced by a large part of the population, the high illiteracy rate – around 70 % – and problems between family members. “We also fight against the vulnerability of many citizens who are exploited by political parties. We urge them to be aware of any manipulation,” Karfe says.

Ibrahim Isa Kufena, secretary of the Muslim movement Jama’atu Nasril Islam, and Reverend Calb Maji, secretary of the The situation improved because now “there is dialogue” between the communities and “there is talk of peace and conflict resolution involving religious leaders, young people and women.” The employees of the Bakhita Initiative, a multi-ethnic team composed of Christians and Muslims, in front of the main façade of their headquarters in Sokoto. Association of Christians of Nigeria, agree on the respect Bishop Kukah enjoys. “I call him ‘my bishop’. He is an upright person, unafraid, who speaks the truth to authorities, to power, a man who seeks nothing for himself and everything for his people, who wants to see them emancipated, free… KC has done a lot, bringing different religions together for peace, to coexist and build on our capacities, not only to tolerate but to accept each other and live together as citizens, regardless of our differences,” Maji acknowledges.

In Kaduna, as in other Nigerian cities where the KC is active, the situation of girls and adolescents is a priority. For decades, boys’ education has been prioritised while the bullying of girls was normalised, a reality that the KC is trying to correct. “Society is changing. Girls can excel if they are given similar opportunities to boys. We need to move towards an egalitarian society,” Karfe concludes.

“KC has done a lot, bringing different religions together for peace, to accept each other and live together as citizens, regardless of our differences”

Most Rev. Matthew Man-Oso Ndangoso, Bishop of Kaduna, finds it easy to praise the Bishop of Sokoto. “He is someone very close to people, with a high intellectual capacity and very popular throughout the country. He is a person with a lot of impact on the Nigerian society since he became a priest. He used to write a weekly article in a newspaper called “The Master Seed”, which became a reference for families. This started his popularity. International recognition and awards followed, like the recent 2023 Mundo Negro Fraternity Award. Bishop Man-Oso highlights the creation of the National Peace Commission, coordinated from the KC headquarters in Abuja, as one of his biggest milestones.

The figure of the priest

“We still have many problems but we must find a way to channel them, as Bishop Kukah does. I think it is good that he is a priest, because he is able to take a stand in any situation with nothing to lose, backed by his age and experience. This is what he has done all his life”, adds the Bishop of Kaduna after categorically rejecting that religion is one of the problems of the current division in the country. “The problem is how religion is practiced. If you know God, you cannot think that religion is the problem. It’s like medicine or food; if you don’t use it properly it can kill you. You have to recognize the nature of God, but many religious leaders are uneducated. People don’t understand their own or other people’s religions.”

At Kaduna Peace Commission, Rebecca Sako, its commissioner, is also an ardent supporter of the KC’s work. They have been collaborating with the KC since the central government established a permanent office in 2017. “The aim is to articulate and respond to crises, inter-religious clashes, conflicts between herders and farmers, other forms of violent criminality, loss of life and property, people fleeing their homes… We analyse what has happened and make recommendations,” explains Sako. She recognises that, in an area where six million people and 30 ethnic groups live, there are places which they cannot access because of insecurity. However, the number of communal and ethno-religious clashes has reduced. “The big challenge now is criminality of bandits or terrorists, some religious, like ISWAP (Islamic State in West Africa Province), who claimed responsibility for last year’s train hijacking—carrying almost 1 000 passengers and lasting four months. They attack communities, kill livestock and steal crops. These are problems which require action at national level.”

Abuja: Governance and leadership

Atta Barkindo has been leading the KC for four years. He is the head of the National Peace Commission Secretariat, and is proud of the progress already made. He defines the KC as “a faith and public policy centre focused on four axes: support for good governance; interfaith dialogue linked to engaged communities; leadership development for the future of the youth; and knowledge, advocacy and preservation of the historical memory”.

“The problem is how religion is practiced. If you know God, you cannot think that religion is the problem.”

What might appear to be ambitious dreams and intentions, such as “good governance”, is in the case of the KC absolutely realistic. There is no shortage of examples of actions being implemented in several states, or instances in which a particular issue was addressed. One of its focuses is on the development of political parties, electoral reforms, political processes with law enforcement. It is a work of accompaniment, observation and critique, in collaboration with the Independent National Electoral Committee. Among the concrete actions, as Barkindo points out, has been the signing of “an agreement to accept the outcome of the vote, to avoid violence and killings”, to ensure “a peaceful, transparent and credible process”.

“The new government must focus on the fact that the problem is not the institutions, but those who run them. Education must provide equal access and opportunities rather than privileging those in power,” Barkindo said. So far, there has been no equality, as shown by the 90% rural illiteracy rate in states such as Sokoto.

In each region, action taken must be different. The KC believes that an end to the “culture of impunity” is essential for progress. “Accountability is the big issue. Fraud, criminality…, institutions which should protect the people are weak, starting with their leadership,” Barkindo adds. He acknowledges the challenge of maintaining neutrality and avoiding the politicisation of projects. Esrom Ajanya, manager of a KC project about political parties, recalls that, for decades, more than 50% of the population has not believed in the democratic processes in the country; that is why they hardly go to the polls. “We need cultural changes because corruption has become institutionalised. We need to question the leaders and also ourselves,” says Ajanya.

“Democracy in Nigeria is at a foundational level because many citizens don’t even know what it is,” says Saka Azimazi, another KC manager of a peacebuilding project. Even so, the level of debate on gender issues, conflict management, mediation and, ultimately, democracy promotion, which the KC demands is very high. Its capacity for effective action is second to none in more developed countries, an example of how the correct use of means, based on genuine self-demand, can transform the most adverse situations. In Nigeria, the KC remains committed to achieving this.